The Serpentine in London plays host to the UK’s first solo show of the Swiss naturopath, healer, and environmental artist.

Regardless of whether or you believe in the divine mysticism of Emma Kunz, there’s no denying she was ahead of her time. Despite keeping little record of the ethos behind her work, Kunz’s equally frenzied and meditative approach has made her a modern-day cult figure.

Often compared to Hilma Af Klint, Kunz lead a very different life from the Swedish innovator of abstraction. She was a true outsider, with no art school education and died never having exhibited her work.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, the artistic director of the Serpentine where Kunz’s first solo show in the UK has just opened, describes her as an “artist’s artist” – adding “she had the feeling that these drawings were for the next century, that they were somehow not for her own time.”

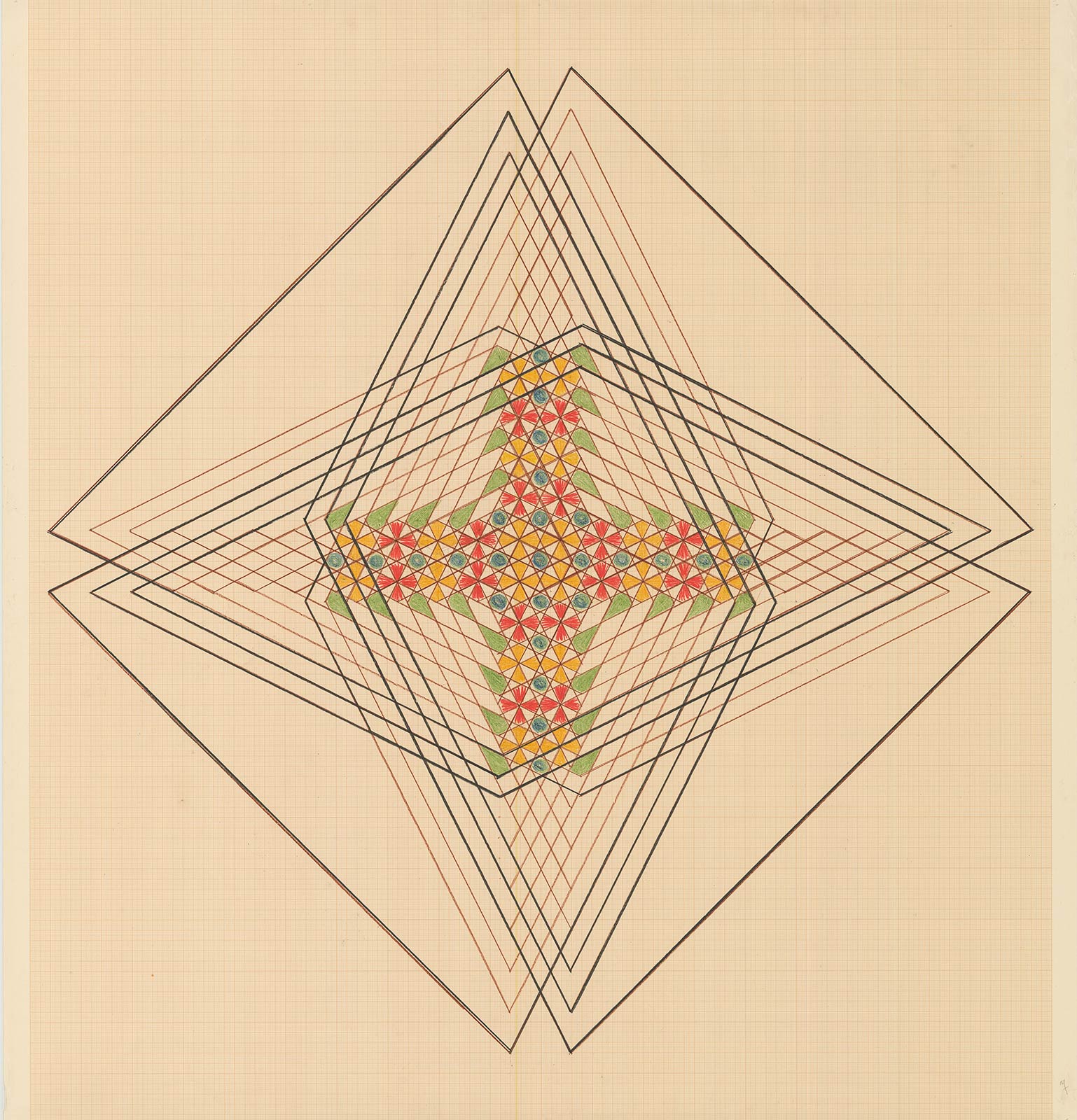

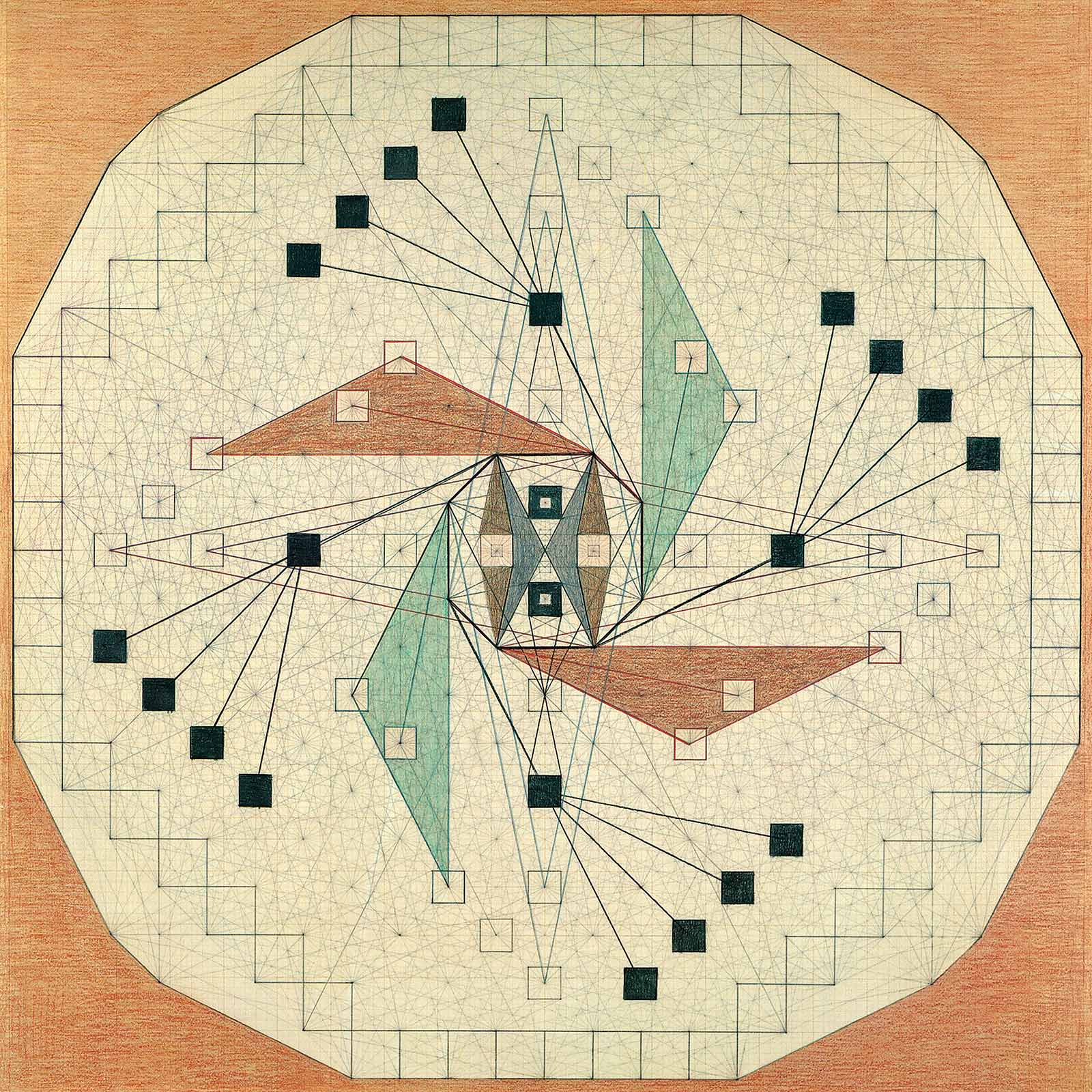

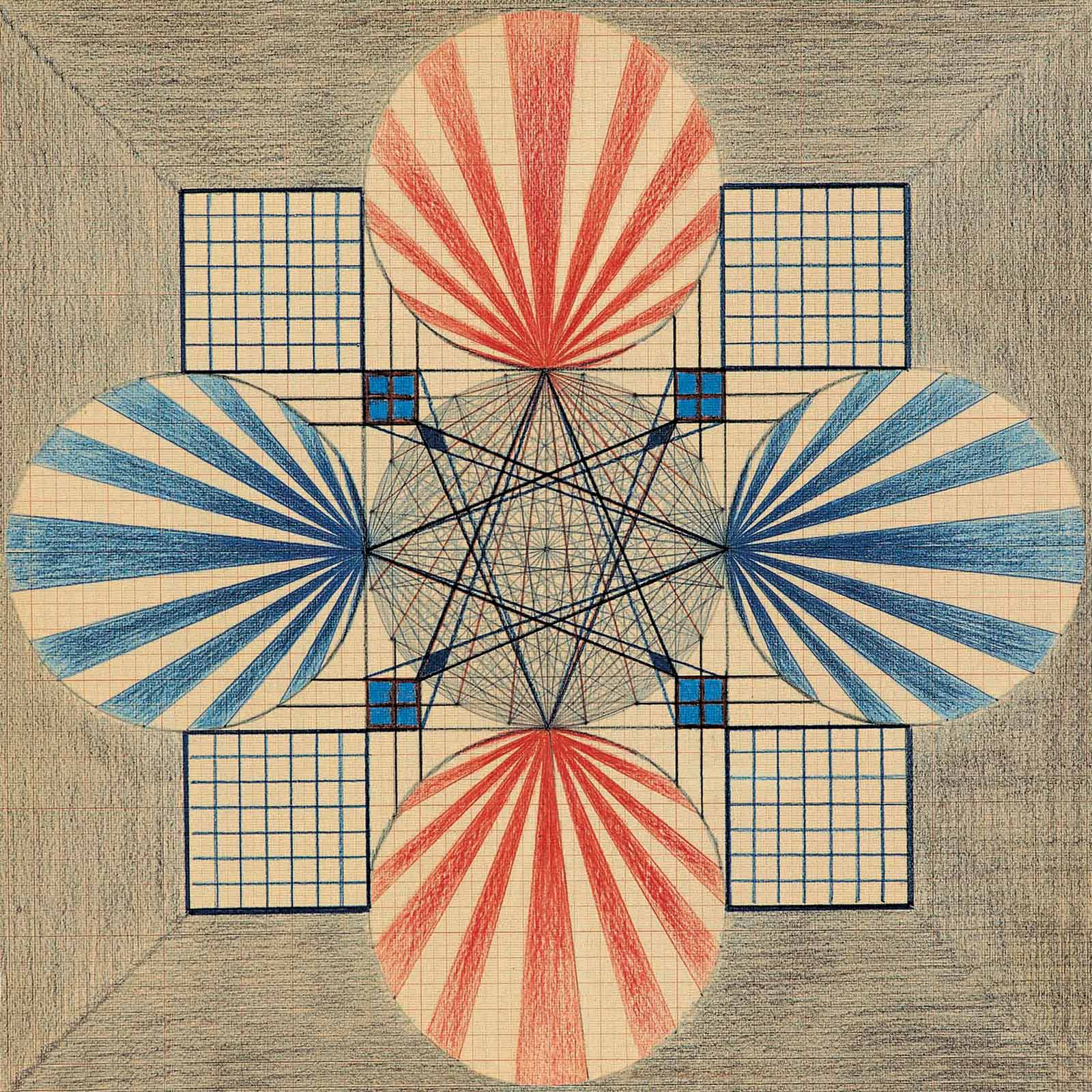

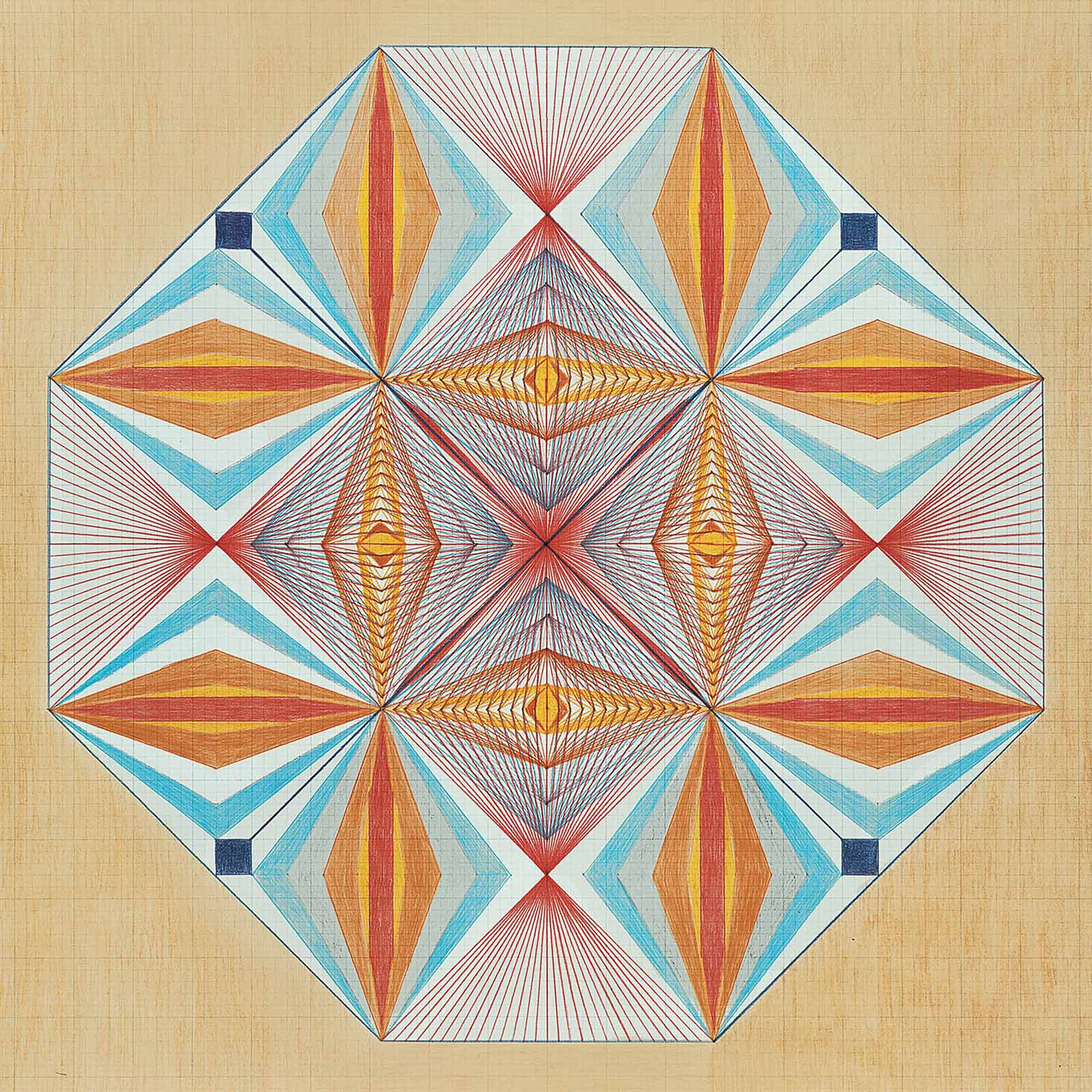

Having spent most of her life in rural Switzerland, Kunz only began making art in 1938—when she was 40. Known for her geometric linear drawings on graph paper, both and her work were ahead of her time. None of her pieces were ever titled or dated and she never inferred any particular meanings. Throughout her life Kunz never allowed her work to be exhibited, permitting a select few to see it but never letting them in the process of how she created them—a practice Obrist describes as “feverish activity”.

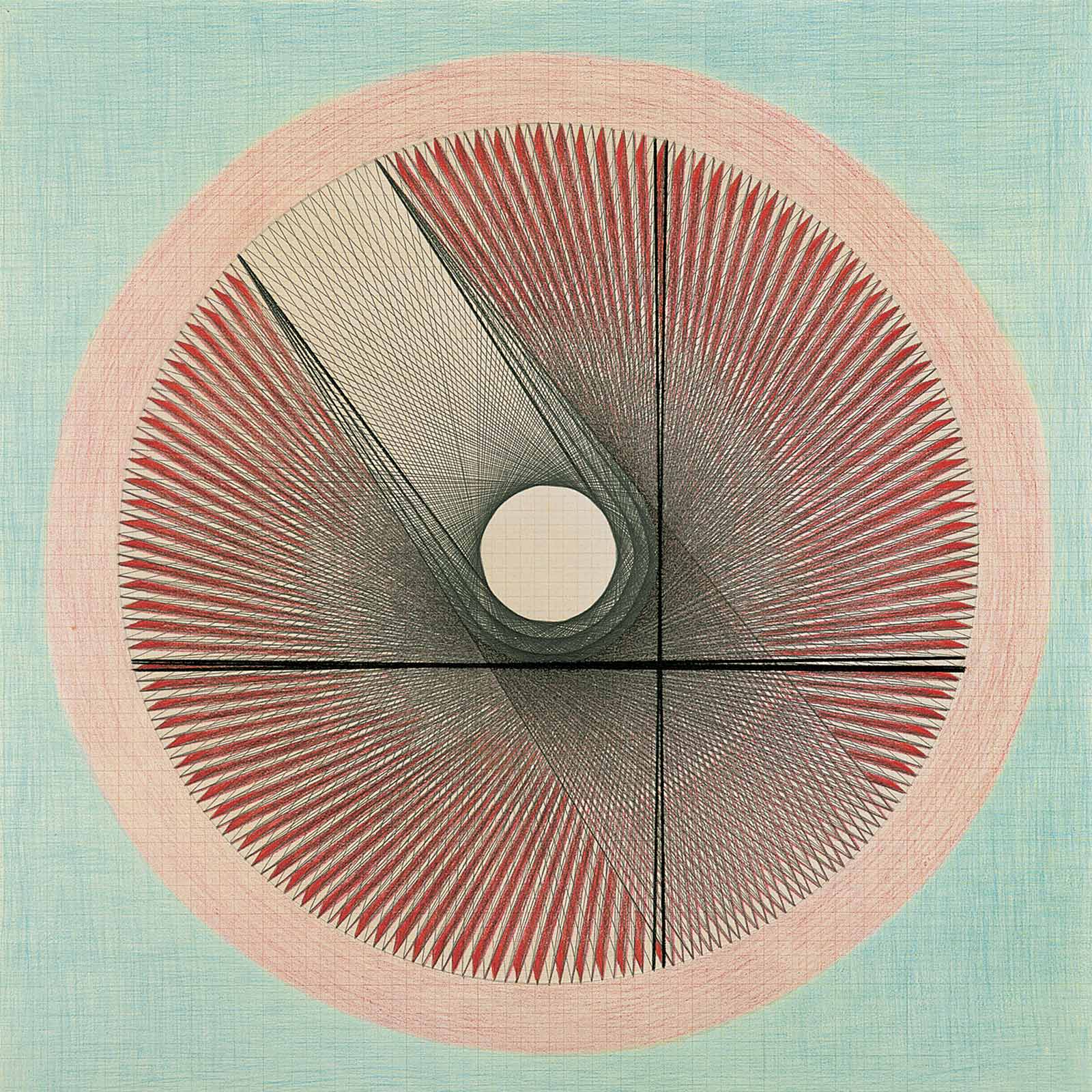

Kunz was obsessed with the idea of mystical energies and was determined to establish a deeper connection between people and the natural world. Over stretches of time that could sometimes be as long as 24 hours, Kunz would create her large-scale drawings with a pendulum, calling on “divine intervention” to help plot the linear compositions. “What’s amazing is the thought of 24-hour sessions of intensive drive where Emma Kunz thought that she could heal the people, the planet and the politics of her time,” says the Serpentine’s CEO Yana Peel.

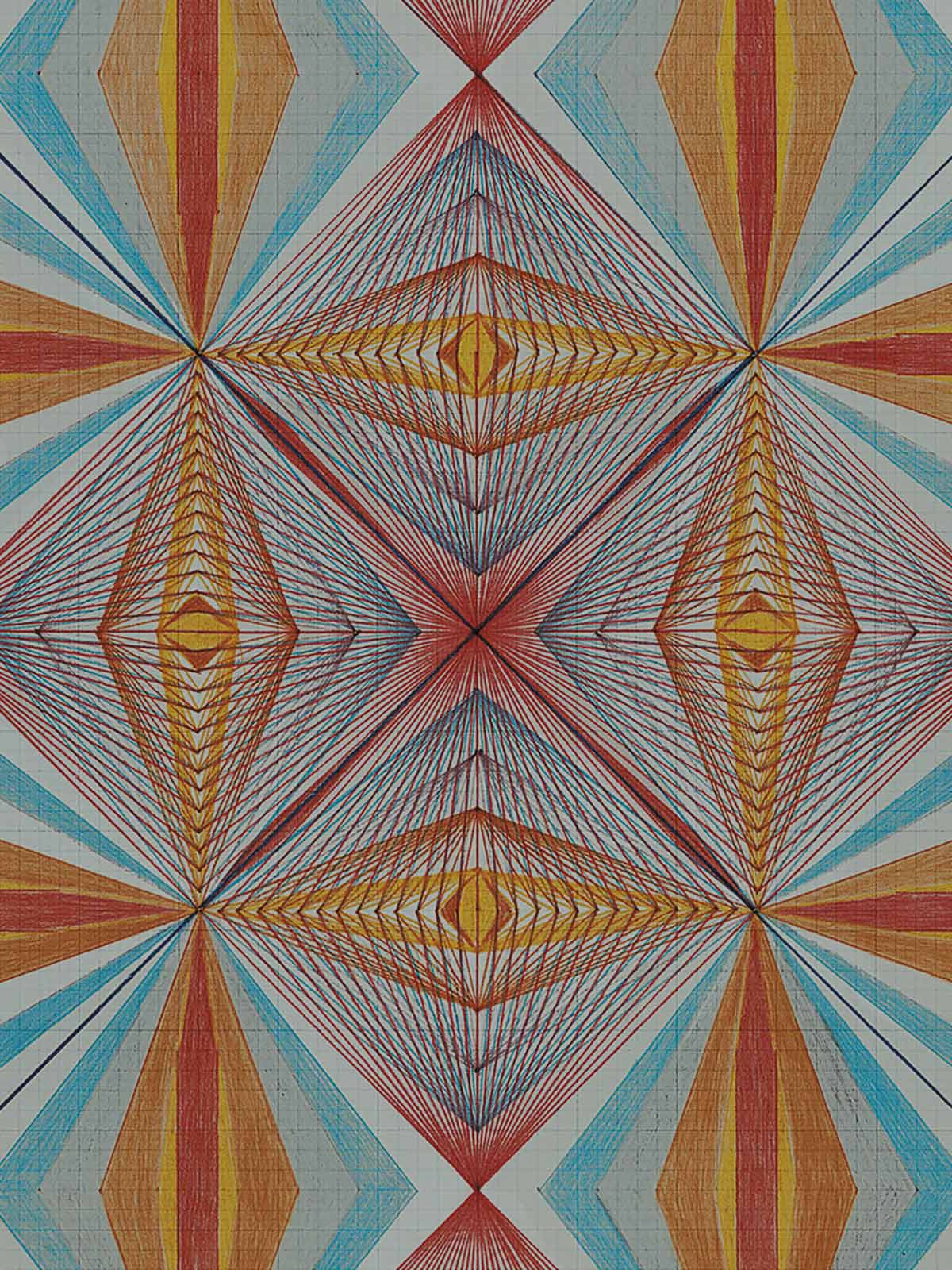

Creating a kaleidoscopic effect by mixing rudimentary materials with repetitive trance-like technique, the colored pencil used to create her geometric lines on squared graph paper may lack the sophistication of an architect’s drawing but they are just as considered.

The 60-piece strong show at the Serpentine is only a fraction of the 400 or so works she completed in her lifetime. The meticulous work of the curatorial team meant the story of her practice, her phases, timelines and development have all been pieced together, has been inferred from archive material housed at the Emma Kunz museum, just north-west of Zurich.

And Kunz’s legacy doesn’t stop at her artwork. She is also known for discovering a type of rock called Aion A, still bought today for its healing qualities. Quarried from a site near Kunz’s hometown that dates back to the Romans, Aion A is sold in pharmacies across her home country of Switzerland—a sight Obrist (who is also Swiss) remembers well. “Emma Kunz’s work, for me, is something that started during my childhood when my mother would always buy this Aion A powder,” he explains, going on to reminisce about its striking packaging. Emma Kunz also happens to be the first museum show he ever organised—in 1991 at the Swiss cultural centre in Paris, where he invited 40 contemporary artists to react to the work.

Over time, Kunz herself has become as ethereal as the mystical divinities she tried so hard to conjure. Conceived with the artist Christodoulos Panayiotou (who has been a fan of Kunz for many years) the entire exhibition fuels the cult of personality that the artworld has built around Kunz since her work was first publicly exhibited in 1973. “We thought it would be great to conceive the exhibition with an artist and through the eyes of an artist,” explains Obrist. Panayiotou’s only visible addition to the exhibition are sculptures (in the form of viewing benches) placed in each room. Made out of the Aion A, they’re an uncanny reference to the persona Kunz has developed posthumously.

As anti-vaxxers and others turn their back on science it’s important to get a perspective on some of the mysticism surrounding Kunz and her work. The term “healer” is as broad as it is vague. It means many things to different people and but it’s often co-opted to make other’s believe things to your own benefit. But that’s clearly not what we can take from Kunz’s work in a contemporary setting.

When you look at Kunz’s work, it’s tempting to scrabble around for a hidden meaning, but that would be to overlook them as visual treats. She uses mysticism as an alternative language; a different way to discuss the power of art—as a medium to explore new ideas, emotions, and concepts at a time when few people were familiar with them, let alone had the verbal or visual language to discuss them.

But mainly, Kunz’s practice called out for a new relationship with our environment. One where we respect and listen to the natural world as opposed to ignoring and inadvertently destroying it. A sentiment that’s never been more accurate.