‘Fabric(ated) Fractures,’ a group exhibition at Concrete in Dubai, tells the untold stories of rape, religious violence, and loss in South Asia.

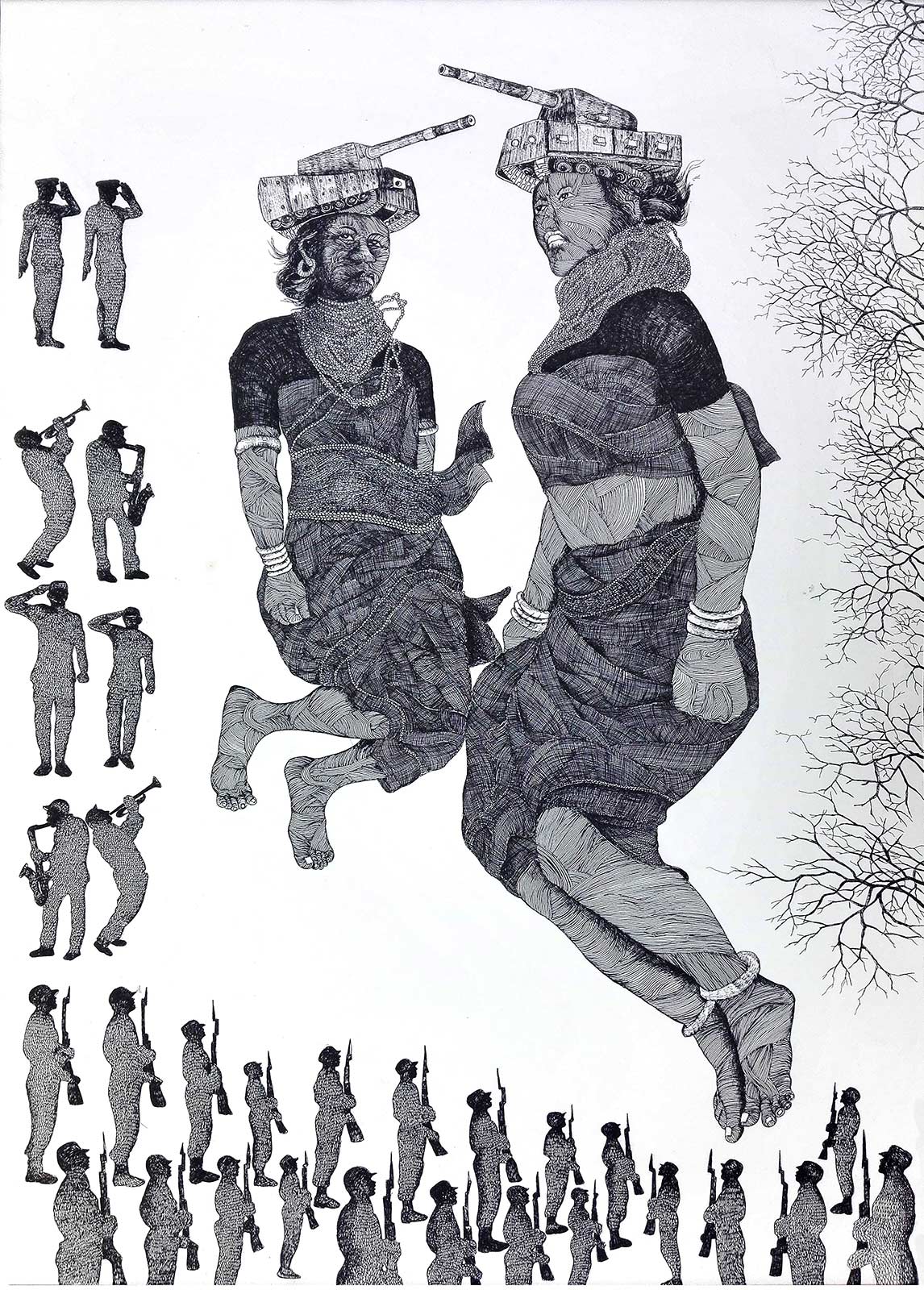

At the foot of the entrance of Concrete—a monumental structure located in Dubai’s Alserkal Avenue designed by OMA, the architecture firm headed by Rem Koolhaas—larger-than-life indigenous women with tanks over their heads tower over tiny military figures. The drawings emulate alpona, the traditional white rice designs made by Bengali women, and are by artist Joydeb Roaja, who is part of the indigenous Tripura community.

“They’re basically priming the space, making it safe to talk about stories that some people might not want us to hear,” said Campbell Betancourt, the artistic director of the Dhaka Art Summit.

The piece greets visitors as they enter Fabric(ated) Fractures, a group exhibition curated by Diana Campbell Betancourt, presented in collaboration with Alserkal Avenue and the Samdani Art Foundation. The exhibition looks at, according to Campbell Betancourt, the absence and presence of bodies, and people’s fight to exist when people are trying to erase their history. “These artists bear witness to violence unfolding in their locales and on their communities, and their work often acts as a register of this trauma, grounding the constricting present in a more porous past,” wrote Campbell Betancourt in the exhibition catalog.

Campbell Betancourt set out to give a voice to artists who reside in these highly politicized places in South Asia, allowing them to present often traumatic narratives of the violence and displacement in areas often overlooked by traditional media due to military occupation. Over the last century, people have been forced to leave their homes because of climate change and changing borders set in place through religion, which clearly doesn’t work because of the plurality of these populations. “They missed the fact that culture is practiced differently than religion and that there’s also plurality in different parts of religious practice,” said Campbell Betancourt. “Bangladesh is also Buddihst and Hindu, in addition to Muslim.”

At the entrance is a piece titled “Heaven Is Elsewhere” by Kamruzzaman Shadhin—an enormous colorful patchwork quilt of clothes collected from people who left them behind as they were trafficked into Southeast Asia, and from the Rohingya community who were forced to flee to South Asia because of religious violence. The clothes were stitched together by climate refugees, who escaped their villages in the south of Bangladesh due to rising waters, as a ritualistic healing exercise using traditional Katta embroidery techniques.

Nearby, artist Ayesha Jatoi delicately folds white clothes (white is the color of mourning in South Asia) in a performance. “How do you put away the memories of love and the pain of loss when someone that you care about is harmed or goes missing?” asked Campbell Betancourt as she described the meaning behind the piece.

Campbell Betancourt highlights the consequences of fake news through a painting by Kanak Chanpa Chakma. It tells the story of the fake Facebook account, set up by somebody in Southern Bangladesh, that posted an image of a burning Quran, causing a mob of 25,000 people to destroy 12 Buddhist temples and over 50 homes. Chanpa Chakma’s painting collaged together images of that incident from newspapers, juxtaposing them against a painting of peaceful Buddhist architecture.

Across the way, the sound of the harmonium, a musical instrument that is part of Bangladesh’s social fabric, is played by 35 musicians in unison as they pay homage to the tradition that is in danger of disappearing. Reetu Sattar placed the musicians on scaffolding in the performance, called “Harano Sur (Lost Tune).”

Artist Ashfika Rahman looked at the use of rape as a weapon to assert control and repress indigenous resistance movements in South and Southeast Asia, and how the rapists are often protected. Her portrait series, titled “Rape Is Political,” depicts photos of victims with handwritten words surrounding them. “A portrait can be a sign of resistance,” said Campbell Betancourt. “Often when rape happens, doctors are pressured not to report it because it’s militarized, and sometimes the perpetrators are military.”

Campbell Betancourt presented Fabri(cated) Fractures as a way to tell the untold stories of violence, religious discrimination, and displacement through art. “Art can give people a voice when people try to silence them,” said Campbell Betancourt.