Document takes a look at the late Sarah Charlesworth’s archive on the occasion of her first exhibition with Paula Cooper Gallery.

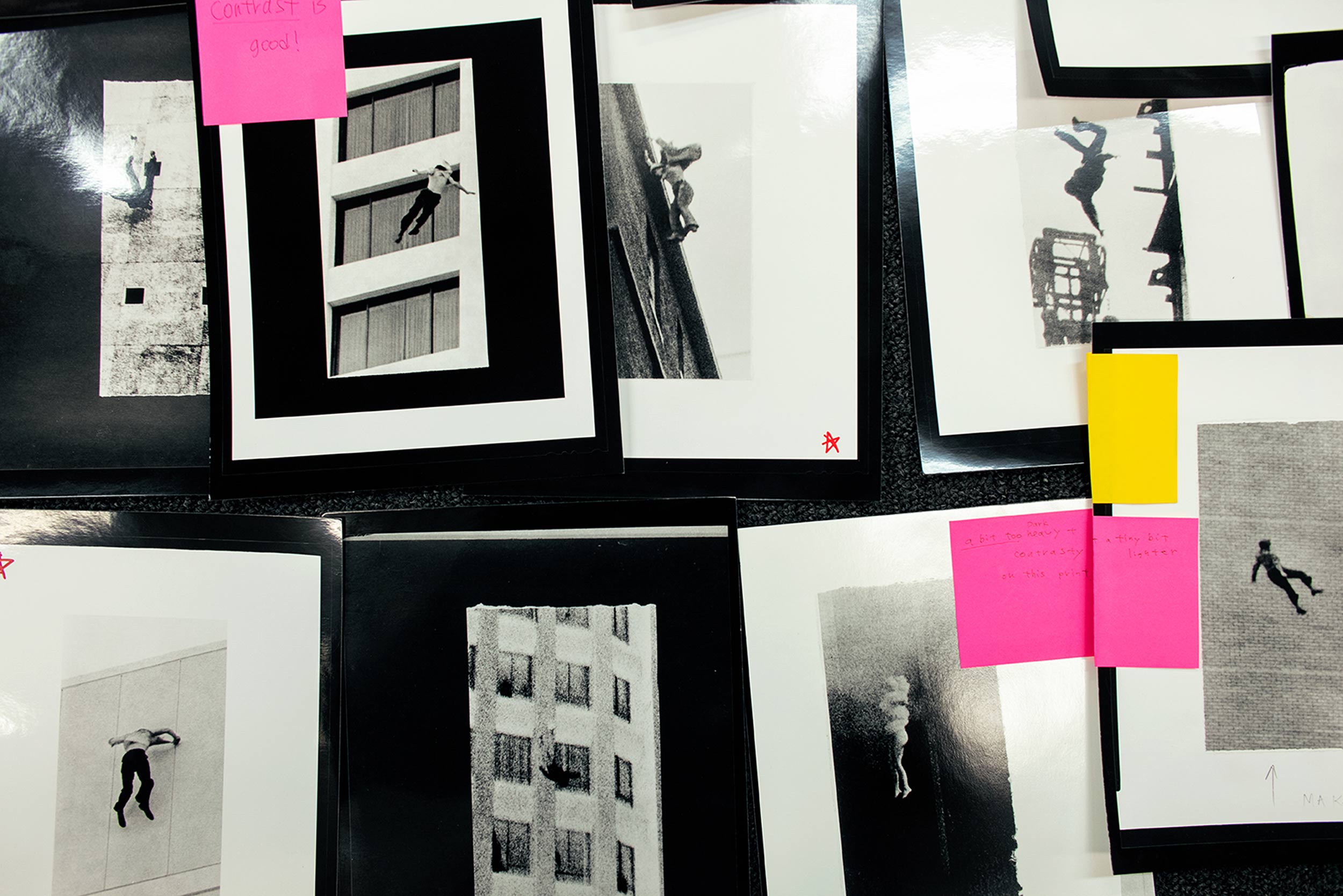

A shadowy figure, suspended mid-air, dangles like a limp, helpless doll. Artist Sarah Charlesworth unveiled a series of seven haunting and mysterious black-and-white photographs in the spring of 1980 in art dealer Tony Shafrazi’s gallery space, which was then located in his apartment buildings. The series, known as Stills, would go on to be a seminal body of work for Charlesworth, who collected images of falling bodies from news clippings. In some ways, the series would toy with its viewers’ heads. Who are these people? Why are they falling? Are they even alive? When the work would go on display again in 2011 in the group exhibition September 11, which curator Peter Eleey organized at MoMA PS1 to commemorate the 10th anniversary of 9/11, Charlesworth was adamant to make it clear that her photographs were collected in 1980.

“Everything she had, all the material, newspapers, torn images are from 1980,” emphasized Charlesworth’s studio manager Matthew Lange. “[She was] very careful not to make it 2012.”

Sadly, Charlesworth—who made her name in the ‘80s as part of the Pictures Generation, named after a 1977 group show curated by Douglas Crimp that also included Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, and Robert Longo—would pass away suddenly from a brain aneurysm in 2013, at 66. Lange was speaking to a small group of visitors to Charlesworth’s storage space in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, where he showed the binders where she carefully compiled the newspaper clippings she collected. A few weeks later, an exhibition showing rare photographs by Charlesworth, who manipulated, collaged and/or layered photographs before rephotographing them, would open at Paula Cooper Gallery through March 23. It starts with her work from the late ‘70s, starting with the series Modern History—where she would manipulate the front pages of newspapers, whiting out their words to leave on the images—and travel through to her early ‘80s Red Collages—where she would layer a piece of red paper with a shape cut out over a photograph.

Charlesworth’s Stills series would grow to become 14 photographs in the official Artist’s Proof, which was put together for the Art Institute of Chicago, who acquired the set. Lange revealed that there were different reasons for the falling bodies. “Some are people committing suicide, others are people jumping from buildings to save their own lives,” he said, explaining that some were never identified, but others, like Patricia Cawlings, who was a child when she fell, survived, but have no trace on the internet, probably because the photographer recorded the name incorrectly.

One photograph that shows a black human silhouette crouching as it falls is actually a joke Charlesworth played; she had reappropriated and photographed the image from Andy Warhol called Suicide (1962) from his Death and Disasters paintings. “This was a joke to Sarah that she thought everybody would get, and nobody would,” said Lange. “There’s falling people, and then this one is a Warhol painting that she tore out and rephotographed…Part of her idea was that it wasn’t all gloom and doom, and death and suicide, that there’s all different reasons, almost this emotional thing.”

Lange—who still manages Charlesworth’s studio, worked with the artist first as a student, then as an assistant, and finally as a colleague in her final years—where he became very aware of her intent behind the controversial series. “She took it very seriously knowing that there’s a history of critique directed towards documentary photographers, and the idea of making disaster porn, and she was really conscious and conscientious of that,” he said. “She wanted to make sure that she wasn’t doing this in a way that was she wasn’t abstracting to a point that it was like making a spectacle of people. She was very conscientious of who was being included and what was being put out there with respect to their lives. She was very worried that this would be making of light of such a scary experience.”

Susan Sontag’s 1977 collection of essays critiquing the role of photography in modern society, titled On Photography, would eventually come into Charlesworth’s possession, leading her to respond to Sontag’s words with photographs. “She decided to take Susan Sontag to task and say, it’s really easy to write a book about photography, but if you really want to contemplate the medium, you should do it from within,” said Lange, who continued, “Is it possible for the photographer to work a different way? Is it possible to make photographs break from that?” It was in this early ‘80s series, which she titled In-Photography, that she would test her medium’s boundaries, splicing or changing images to disorient the viewer, while also creating an abstract puzzle of pieces and colors.

Throughout the visit we would learn that Charlesworth didn’t only collect newspaper photos of people falling; she also collected blast-offs, missiles, and explosions; that she would have been a hoarder if she wasn’t so organized; and that she created an image of a lightning bolt striking the Empire State Building for the first cover of Bomb, the magazine she co-founded in 1981 with Glenn O’Brien, and a group of other artists and writers. Charlesworth was very aware of the power of the image, and her way of manipulating and photographing them would cause many to question their origin, their validity, and their truth—something especially important in this heavily filtered era of Instagram—or to simply admire their beauty.