Document senior editor Ann Binlot writes on her search for representation of her Filipino heritage only to find it through the art of contemporary artist Maia Cruz Palileo.

“You look like a Gauguin girl,” some guy once told me, referring to the curvy, brown-skinned women with long black manes that the French artist Paul Gauguin painted during his sojourns in Tahiti during the late 1800s.

I wanted to vomit.

As an American born to Filipino immigrants in the San Francisco Bay Area, I rarely saw people with my likeness who weren’t my relatives while growing up. That would soon change as more Filipinos would move to the United States in the ‘80s and ‘90s to become the fourth-largest immigrant group in the United States, behind Mexican, Indian, and Chinese immigrants.

Around a decade after the Gauguin comment, I would become an art writer, yet I would never see people with the same roots as myself depicted on the canvas. I remember observing the porcelain-skinned European faces at leisure in French Impressionist paintings, the emotionally charged self-portraits of Mexican art power-couple Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, the regal portraits of Black Americans by Kehinde Wiley, and, of course, the Tahitian women in Gauguin’s paintings. Why did other ethnicities have this privilege? Where were Filipinos in art?

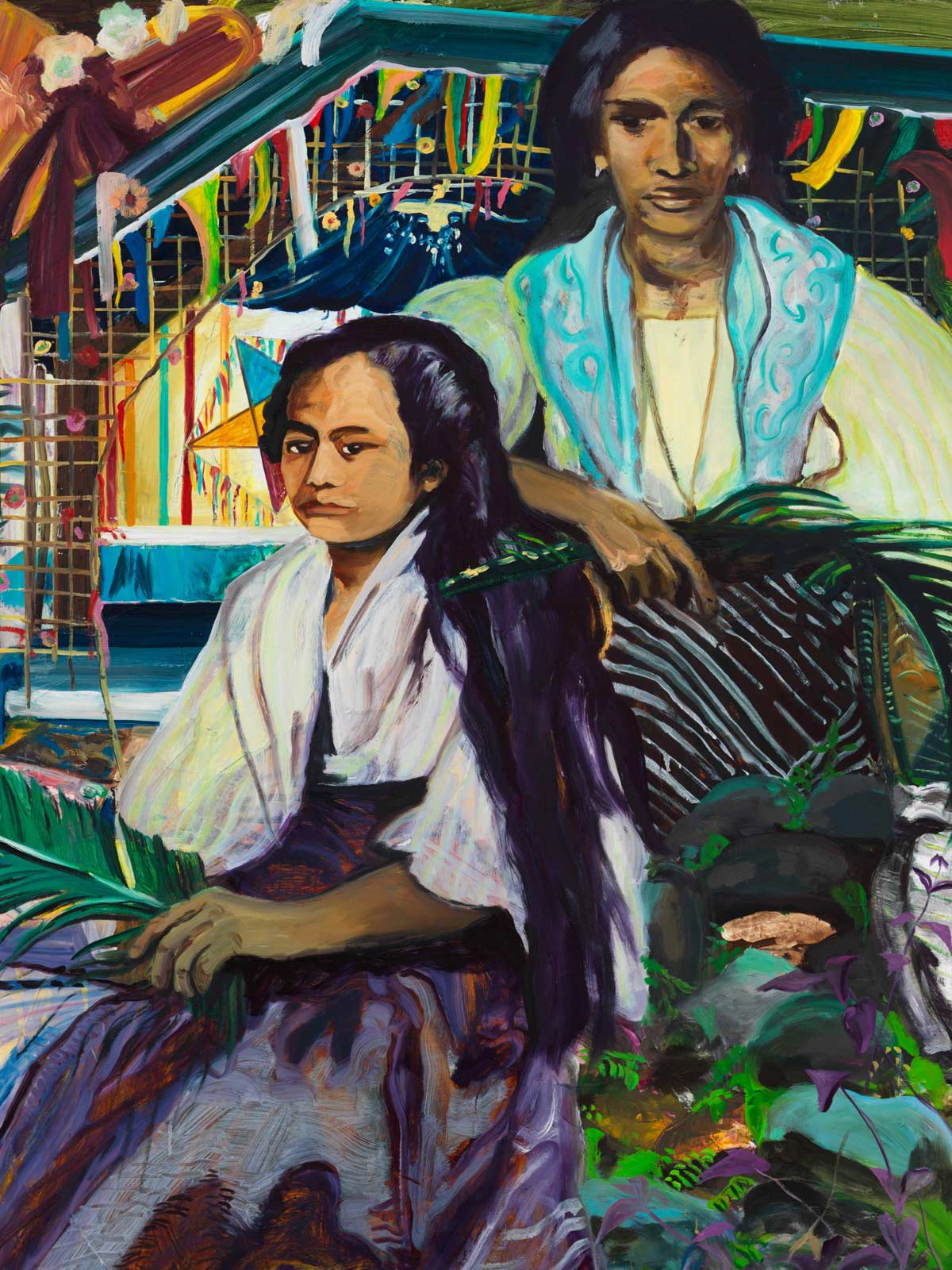

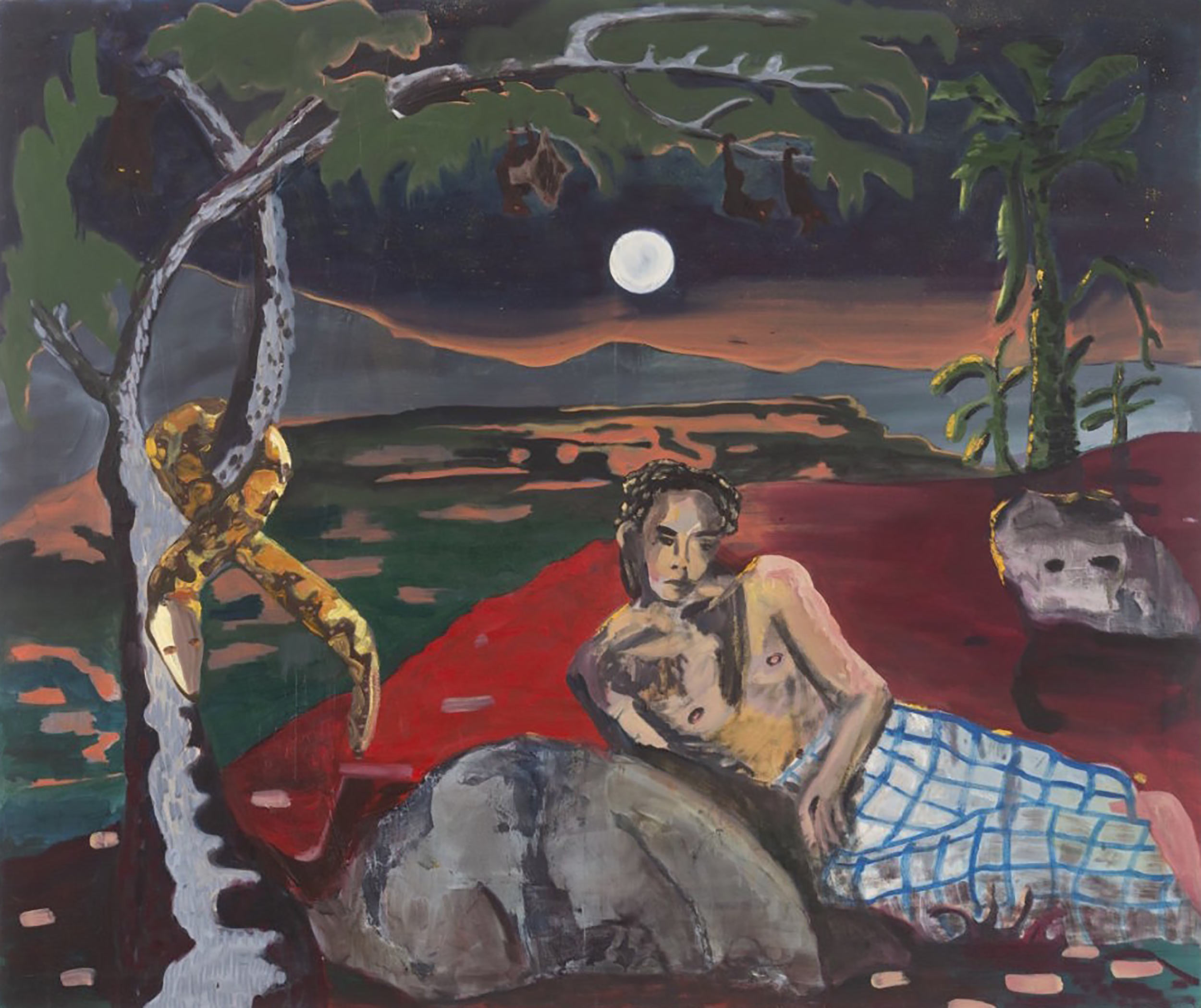

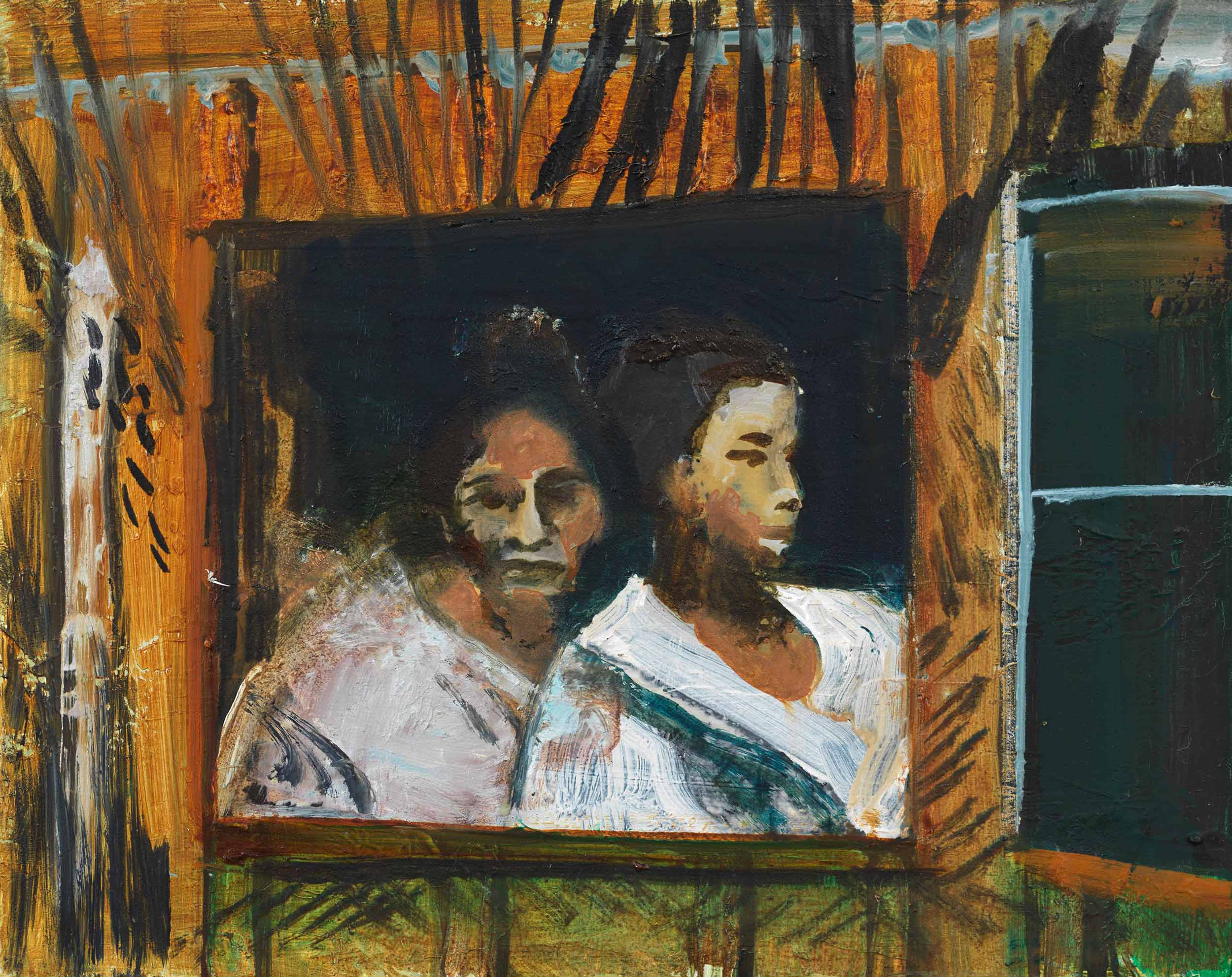

Last December Monique Meloche, a Chicago art dealer who is a friend of mine, told me she was going to have a show by a Filipino-American artist named Maia Cruz Palileo. When I saw Palileo’s paintings, I was again in awe. The faces in her work could be that of myself, my ancestors, aunts, or uncles. The men in her paintings wear Barong Tagalogs, the traditional, transparent embroidered dress shirts worn by my own father for special occasions, while the women donned Maria Clara dresses, also formal wear, inspired by traditional Spanish clothing. Finally—my own people, painted by an artist my age, who like myself, grew up in the United States.

The first time I saw Filipinos portrayed in art at a museum was at the National Gallery Singapore in 2015, where I saw Juan Luna’s 1884 portrait of the colonial relationship between Spain and the Philippines in España y Filipinas, and Galo B. Ocampo’s 1946 work of a woman getting her groove on titled Moro Dance. I felt validated and awestruck, especially when I learned that the Philippines has a strong history of artists—their work just hardly ever made it outside of Asia. A few years later, in 2017, I would visit the Philippines, where I would meet artists from there and see their work in places like Bellas Artes Projects, a non-profit art space; a gallery called Silverlens; and the Ayala Museum. In the States, I noticed that portrayals of Filipinos in contemporary art were still rare, despite some 3.4 million (according to the 2010 US census) of us living here. Last summer, I was introduced to the work of Monica Kim Garza, an American who has a Korean mother and a Mexican father. Like the Gauguin women, her muse was curvy, tan, and black-haired—similar to my own image, yet not.

Palileo’s work, which is on view in an exhibition titled All the While I Thought You Had Received This at Monique Meloche in Chicago until March 30, tell a story that, according to the artist, makes “more connections to larger historical contexts of erasure, assimilation, and violence” that Filipinos have experienced.

Unlike me, Palileo first saw Filipinos portrayed in art at a young age, in her own home and in the homes of the extended Filipino family she had in the midwest. “My parents had a painting of a Filipina woman sort of in the style of Fernando Amorsolo—a traditional, softly lit, warm colored, nostalgic type of painting,” recalled Palileo, who continued, “My godmother had a little painting of a boy on a caribou and I always thought the boy looked exactly like my cousin Justin when he was little. I would always point out the painting and say, ‘There’s Justin!’”

But, outside of her family life, Palileo’s experience was like my own. “I never saw any [Filipinos] in school or in the few paintings I was aware of growing up,” she remembered. “I was more aware of Filipinos in entertainment, like when a housekeeper, pirates, or Ewoks would speak tagalog in a movie, we’d all cheer—ah, the ‘80s—or be proud that Enrique Iglesias, Foxy Brown, and Bruno Mars are all half Filipino.”

It was only when she began painting that she started to take a closer look at Filipino artists and depictions of Filipinos in art. In 2017, through the Jerome Foundation Travel and Study Program Grant, Palileo took a close look at the so-called father of Filipino painting Damián Domingo’s art at the Newberry Library, where she also searched through its vast archive of photographs, art, and manuscripts from the Philippines during the 17th and 18th century, when Spain ruled the Southeast Asian archipelago, just before the US beat the Spanish at Manila Bay in 1898. The experience, said Palileo, was “the most up close and personal I’ve been to any historical work of art, really, and that was an incredible experience.”

Her research, in which she discovered revolutionary Isabelo De Los Reyes’s 1889 book El Folk-lore Filipino and Nick Joaquín’s stories, informed the body of work that’s on view in the exhibition. In it, I see the history of our people, from delicate cut-outs of indigenous Filipinos set against the lush, tropical landscape of the Philippines, to rich, gestural paintings featuring subjects, who, like me, have almond-shaped eyes, brown skin, and black hair. Palileo’s timeless depictions could either be from Spanish colonial rule, or present day. They tell the complex, fractured narrative that makes up our history. “I’ve always been drawn to where my family came from, what it was like for them growing up in another country, and how their stories helped me to form a sense of belonging and identity,” said Palileo.

Palileo’s work gives me a sense of belonging and identity. I thank her for the rare opportunity to finally see my likeness in art—a subject I know well, but a format in which I rarely see people like myself with the same history as my own. It’s about time.