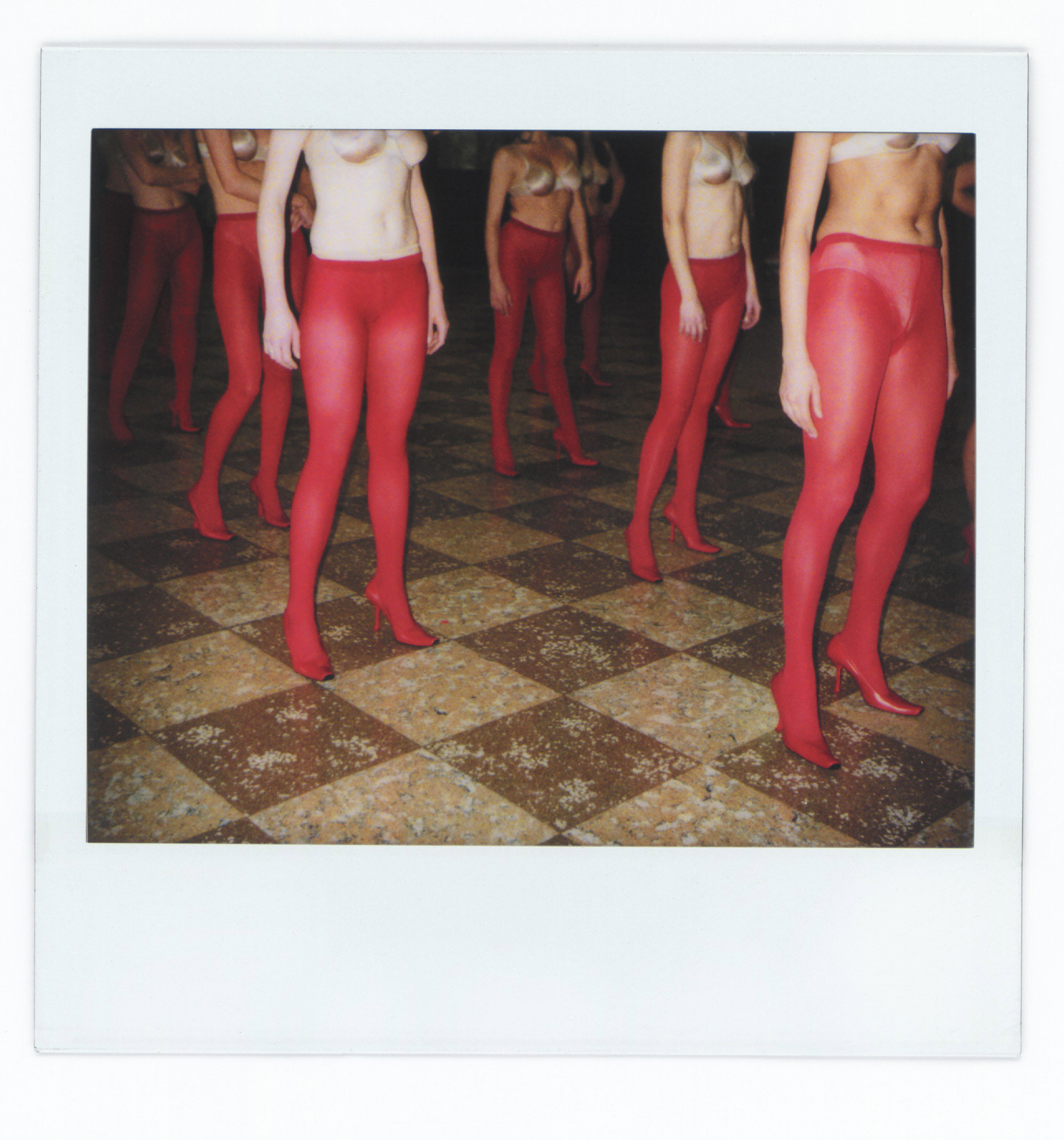

The artist known for staging larger-than-life human performances, shares an intimate polaroid diary as she prepares to stage her largest performance to date for Document's Fall/Winter 2013 issue.

Vanessa Beecroft, the somewhat elusive artist known for her elaborate and site-specific staging of human tableaux is set to unveil her latest retrospective this November at Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art. With a casting call for over 300 models, this will be the largest staging of her work to date. Traveling between her home in Los Angeles and native Italy, the artist pauses for a moment to discuss the relationship between saints and models with Document.

Rebecca Roberts: For your upcoming retrospective, you are including 10 replica performances and one new piece. How did you decide which performances would be in the exhibition?

Vanessa Beecroft: The idea came out of a recent meeting I had with Jeffrey Deitch just a few weeks before he resigned from MOCA. He reminded me of an idea I had in New York for a show in which I would simultaneously do seven performances, each with a different color base, as if they were monochromes. He thought I could do a retrospective of performances from the past that were very iconic and different from each other. When selecting the past performances, I went with the same criteria, finding the ones that were iconic but also color based. The new performance would be an open call where women would walk in and be modified slightly on stage, so that the number would be unlimited. For this, I asked American Apparel to help cast women in Los Angeles of different ethnicities, primarily Latino. American Apparel picks up girls on the street, like I used to do when I started my career back in 1993.

Rebecca: How long would the open call piece be going on for?

Vanessa: Usually it’s two to three hours, but I’m really there for a day. I don’t rehearse. Nothing happens previous to the performance except collecting, for example, shoes, wardrobe, whatever I need. But the girls go on stage without any preparation. They’re just given some rules that are always the same since 1996: Not to talk, not to move, not to laugh, not to smile, not to look sexy or act sexy, but to be plain.

Rebecca: How will this casting differ from the ones of the previous performances?

Vanessa: In London in 2000, for example, I picked women that resembled Queen Elizabeth, and then variations of Vanessa Redgrave, Twiggy—particular British icons. Or in Vienna in 2001, women had to look like Helmut Lang. Every time, women are cast based on a painting reference, a photo reference or autobiographical images. This time, it would be just anybody. And of course, every time, I’m sensitive to the location, so I wouldn’t cast white women in a place that you wouldn’t find them. For me, I prefer if every type of woman can be looked at as if she was a painting. In the history of painting you have so many different images of women; however, I have a particular feature I like and am prone to, which Jeffrey Dietch has said kind of looks like my relatives somehow. I guess that shows that I was trying to find an extended family with women. They were kind of representing me, but this doesn’t always mean they physically resemble me. In this case, it will be different because anyone will show up, and I will have maybe a minute to conform them and fix them in a way that would have an iconic look and not be messy. That’s my biggest fear, to be messy. But I usually set the performers to be very clean and organized based on order and rules and color, and then I let the women break the composition and mess the whole thing up by themselves. By staying for so many hours, they can actually sit down and do whatever they want.

Rebecca: It’s a distinctly different experience interacting with the performances live. Is there a fear that the intentions may change as they change state?

Vanessa: In a way, I don’t mind people feeling the sense of loss and emptiness of someone that has gone away, but that was basically what motivated me to work on performances, because it was only lasting one day and then you were left with the memory of it. What I’m more afraid of is photography, because somehow it kind of misrepresents the performance. Apart from Polaroids or low-resolution images that I took, all the other images that I organized from other photographers had a look that was not really faithful to the performance itself—it was stronger, glossier. The performance is a very human event. The women are very weak, kind of strong and weak at the same time. They are being watched, looked at, so they’re very vulnerable. They’re objectified, but also powerful looking back at you and making you feel bad because you’re looking at them. The intensity of the performance is not reproducible.

Rebecca: In the photographs, the work can seem easier to classify as a product of fashion or culture, but in the flesh, they have much of their own confines and vulnerabilities, and occupy a space that is consistent with the viewer but also vastly different—I think both situations have this idea of displacement. Is this friction something you discovered after you began making the works or was it something you were looking for in the beginning?

Vanessa: Somehow I think the need to reproduce the performance with photography was motivated at the beginning by viewers wanting to keep something and then my obsessiveness of trying to create the perfect image and also it being the ’90s, when photography was really exciting because all of a sudden you could use a digital camera. It was the beginning of all of that and the moment in which many other artists and photographers were working on this type of pioneerism. So, at the moment, there was a reason for that: It was really the ’90s. Looking at it now, it feels quite dated. Some images for me, the references were classical paintings, but then the tools I was using were digital camera, Polaroids, video, so in a way, it was a different image, a different work. Now, I’m not so keen on it, even though I want to reproduce the performance because somehow it’s like a photo album of a family. I want to grab some memories of it for sure.

Rebecca: That’s really the beginning of conceptual photography, which is about documenting the performance.

Vanessa: Yes. However, today, I want to stay away from it because I realize that I want to give an image to the art world and I’m trying to do that through drawing and maybe sculpture instead of photography, because photography is too flat somehow, and I’m not a photographer. I just do it to document.

Rebecca: So you’ve referenced painting and drawing. What is your background artistically and how did you come to the performance piece and also, how much of Italy, which is such a birthplace of art, is crucial to your work?

Vanessa: I was raised in Italy. My mother is Italian. My father is British. I was raised in Italy feeling like a foreigner because my mother was different from most Italians. She was vegetarian, feminist, she got rid of my father, she had no car, no phone, no TV, no meat, no nothing. So it was a bit of an unusual upbringing, however, it was in Italy, and we were surrounded by paintings everywhere—from the street to churches, museums and the opera. That early formation was very strong for me, especially because you didn’t have much technology, all you had was to go out and look at museums and old stuff. Nothing contemporary. Everything was old. So I started to connect images of the saints and Madonnas and baby Jesus and look at them and then look at the street and see models on the street in Milan, where I was studying. So I kind of saw saints and models as the same. Then eventually, I started casting women on the street, and my first show was a collection of girls I found inside the Academy of Fine arts in Milan. I stripped the girls naked as soon as I could, because it took a while—it took up to 35 performances to get to a nude one. That was the Guggenheim in 1998. There were 20 girls and only five could be naked; the others had to wear Gucci. So it was always this compromise. I could never really do officially nude women in a public space because it was not allowed. I realized there was still, with that, showing a body that was naked in front of an audience of perfectly dressed people. Even if they were art people, people that would expect to see anything, they were still upset. And they are still upset. I prefer to irritate the audience than try to confront it intellectually.

Rebecca: When you deal with something like nudity, people can demand literal answers; it’s about feminism or it’s about body issues, but if you don’t dictate that, then the audience is really made to confront it rather than the works confronting them.

Vanessa: Yes, and in fact I was studying Brecht when I was young and Brecht was always trying to use a mystery style in which the audience has to figure out the final outcome by themselves. I’ll put it in front of you and you’ll deal with it. Of course I want to protect the woman. It’s in an art institution. It’s not in the street. It’s not explicitly vulgar because she’s just nude, and I always instruct the girls to be plain and be classical and not to engage with the audience and not to be sexy. To feel dressed. They are wearing nothing, but they’re wearing something that is nothing, so they have to be very conscious of that. I don’t want to train people too much. I like the roughness of a girl picked from the street. Each girl reacts differently in a performance. But at the end, it’s like a choir, in which all of them are in unison; they are together like an army.

Rebecca: There is camaraderie that I am sure emerges, being placed in front of the viewer, that in a way develops as the performance moves on.

Vanessa: There is a lot of empathy. Sometimes women and men react differently, but sometimes they react the same, and each of them projects their own fears or their own culture. I’m very pleased when people understand my work. I feel moved because it means they went through the whole thing and they still accept it. Aesthetically, I never really like my work. I wish my work were like a white monochrome or abstract expressionism. I don’t like figurative art. When I look at my pictures I just don’t want to look at them because they’re too descriptive. There is too much in it.

Rebecca: When you see all of these pieces together as monochromes, will it feel more like a painting?

Vanessa: I hope when I do this project, the fact that there are so many and at the same time, it will somehow eliminate the particularity and then show on one hand the humanity and on the other hand that they are very color-based, very minimized as if they were painted, as if they were an abstraction. I can’t do a white monochrome. I try and then I look at them and they are just not good enough. They seem to me too flat. I have a lot of urgencies to express. I couldn’t do it, but I really like that type of art.

Rebecca: What are you most looking forward to in seeing these works all together 20 years after your first performance?

Vanessa: I would like to show people that this is one work. So even if it’s in a length of time, I like the fact that it’s one thing, and hopefully this time, purified by details. I would like it be more like a big group portrait. Strong and uniform, in which you see that all the different works are just one, and still dealing with the issue of the model in front of the painter, looking at her and trying to figure something out, either visually or trying to communicate something for the subject. What are they about? I still haven’t really figured it out, as a gender. I’m still not clear what it is about, but it’s definitely something about beauty and melancholy and a little bit of abuse. Even in the fact that they’re still beautiful.

Rebecca: I know you are sensitive to locations where the works exist—how do you feel about staging this piece in LA?

Vanessa: One fear I had in LA, different then in Italy, is that people are used to seeing so much in art that even if they see a Vanessa Beecroft performance, they aren’t going to be blown away. They understand. Then you go to New York, and they understand but they act more aggressively: ‘What is this? Is this fashion or is this art?’ Then you come to LA and it’s so complicated to come here and do a piece. I was a bit scared in LA at first. At the same time, LA is a very interesting city. But it is having a revival. People are working very hard here. There is a sense of freedom, just by yourself in your car, thinking—there is space. I feel like it’s a free place, and then there is the Hollywood world, which isn’t necessarily my ideal, but there is content, so you feel all of it. It’s quite international, very multicultural.