At Nassau’s Baha Mar resort, the FUZE Art Fair is putting the Bahamas on the global art map—taking the nation to the Venice Biennale while reshaping the cultural future of the Caribbean

The walk to the FUZE Art Fair isn’t short. From my hotel room at Baha Mar, it takes nearly fifteen minutes—through a warren of corridors, across the towers of three hotels, and through the casino. The casino floors are devil red, patterned to keep you disoriented but in motion. Casinos are designed with certain principles in mind: no clocks, no sharp turns, oxygen-rich air pumping through the vents to keep you alert. Everything is calibrated to disarm the parts of the brain that make you stop and reconsider. As I weave through the slot machines and blinking lights I wonder whether any of that same science will make its way into the art fair—whether FUZE, held inside a luxury resort built on the art of persuasion, will coax people into buying art the way casinos coax them into playing. The expectation, walking in, is that it might.

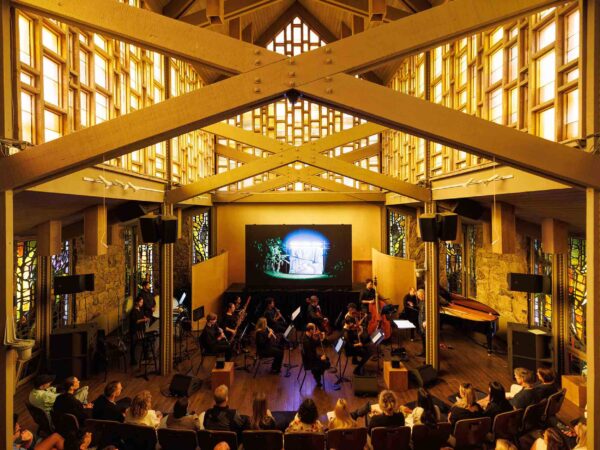

But FUZE turns out to be something else entirely. The fair feels improbable: an event devoted to Caribbean art and dialogue, staged not in a museum or civic hall but inside a corporate resort on Nassau’s Cable Beach. Roulette wheels hum just out of earshot as paintings and video works hang against temporary white walls. Tourists in swimwear wander past installations by some of the region’s most compelling artists. Now in its third edition, the FUZE Caribbean Art Fair has become a center of gravity for the region’s cultural scene. This year’s edition made headlines with the opening-night announcement that Lavar Munroe and the late John Beadle will represent the Bahamas at the 2025 Venice Biennale—only the second time the country will have its own national pavilion. For a small island nation of just 400,000 people, the announcement marked a breakthrough moment, signaling that Bahamian art is not only visible but structurally organized on the global stage.

The partnership between Baha Mar and the country’s cultural agencies has been key to that ascent. The resort, which houses one of the Caribbean’s largest art collections, provided every booth at FUZE free of charge, making it possible for artists, galleries, and institutions from across the region to participate. It’s an inversion of the typical art fair model—less market, more meeting ground. The hotel’s creative arts director, John Cox, has been described by participants as a kind of quiet architect of the region’s new cultural infrastructure: an artist using corporate patronage to engineer access.

That access was felt immediately. For Yasmin Hadeed, who runs Y Art Gallery, Trinidad’s only dedicated contemporary art space, the invitation came as a lifeline. “We feel so isolated,” she told me from her booth, surrounded by Trinidadian painters and sculptors. “Coming here, it’s like, okay—we can do it. What are we doing next? There’s a broader vocabulary for us now.” Hadeed’s gallery, like many across the Caribbean, rarely has the means to show work internationally. At FUZE, she wasn’t alone. The National Gallery of Jamaica and Alice Yard from Trinidad joined in, sharing space and conversation with Bahamian, Barbadian, and Caymanian artists. “It’s a regional conversation curated by people who work in the region,” said Monique Barnett-Davidson, senior curator at the National Gallery of Jamaica. “We have not just artists from the Caribbean, but also from the diaspora. It gives you a microcosm view of what the Caribbean ecosystem is like.”

Blue Curry, a Bahamian artist known for his conceptual critiques of tourism, pointed out the rarity of such a moment. “It’s really difficult to be a gallerist in the region,” he said. “Most places that call themselves galleries are tourist souvenir shops or frame shops. So the fact that Yasmin, a serious gallerist, can come to an art fair like this—it’s her first time—John has created the format.” The fair’s structure, he added, “creates space for an ecosystem that didn’t exist before.”

I met a married couple, collectors from Brooklyn who had flown in specifically for the fair seeking out African and Caribbean artists. A woman I met on the plane, a finance executive from New York, was attending for the third time—not to buy art, but as part of an annual girls’ trip. “Lenny Kravitz brought us here,” she said, laughing. Later that evening, I found myself standing beside Munroe and the hotel’s arts director as Kravitz rehearsed for his performance. He sang “It Ain’t Over ’Til It’s Over” to an audience of three: his crew, Munroe, and me. It was a surreal, intimate moment—art, luxury, and sincerity folded together under fluorescent stage lights. That is FUZE’s peculiar magic: improbable encounters that only happen at the edge of commerce.

In the Bahamas, artmaking has long been synonymous with Junkanoo, the annual carnival of parades and towering floats that spill through the streets on Boxing Day and New Year’s. It’s the country’s most accessible form of creative expression—a fusion of sculpture, music, costume, and choreography that involves entire neighborhoods. During the fair, Munroe invited me to visit a Junkanoo shack—a former slaughterhouse on the edge of Nassau where artists work year-round on floats and costumes. Inside, a dozen men bent over fifteen-foot-high structures of metal and cardboard. Some floats were shaped like Hindu temples, others like teddy bears and hearts. The air smelled of glue and felt paper.

“That guy,” Munroe whispered, gesturing to one of the builders, “is a street person. Dangerous. But here, he’s the boss.” The irony lingered. In Junkanoo, the social hierarchy collapses: doctors, janitors, gangsters, and government sons all answer to the most creative person in the room. A system built not on wealth, but imagination. Watching that transformation—a feared man leading a team in designing a monument to maternal love—I began to understand FUZE differently. If Junkanoo is how most Bahamians first encounter art, FUZE might offer them a second way: a quieter, more contemplative space where creativity meets dialogue.

“We’re creating a blueprint…The first pavilion was largely led by foreigners. This time it’s 100 percent Bahamian—Bahamian curator, team, production. We can do it ourselves, and we can excel at doing it.”

Throughout the weekend, groups of Bahamian schoolchildren were given tours of the fair. “You could see their eyes light up,” Curry said. “That’s what’s most important.” For Hadeed, the moment echoed the purpose of her own gallery back home. “It’s about exposure,” she said. “When the kids see this, they can imagine themselves in it.” Those scenes of discovery repeated across the fair’s aisles—artists explaining their work to students, curators leaning in to offer context, hotel staff stopping on their breaks to look. In a country where art and tourism have always been intertwined, FUZE was reimagining what it means for them to coexist.

But the fair isn’t without tension. For years, Curry had refused to participate, feeling conflicted about showing in a resort that symbolized the very tourism industry his work critiques. “For my entire career I’ve made work that engages with tourism and the stereotypes around the Bahamas,” he told me. “I was conflicted. But this year, I proposed something critical of the resort—and they let me do it.” His project was a suite of seven vinyl stickers installed around the venue, each printed with short provocations: Decenter Resorts and Paradise LOL. “All of the art in this country can’t be filtered through the resort,” he said. “There are limitations to what artists can do here—they know what tourists want, what hotels want to buy.”

Curry talked about the kind of work that can survive in a corporate space like this. A resort comes with rules—spoken and unspoken—about tone and what’s acceptable. “We’re not going to have a performance here of a naked woman writhing in ketchup,” he said. The point is structural: once a resort becomes the center of national art, the art adapts to the environment that enables its financial feasibility. “That’s the danger,” he said. “If everything happens in the resort, the art becomes tame. You lose the edge.”

For him, “decentering” is about preservation—building other places for artists to take risks. He imagines studios, warehouses, artist-run initiatives, even informal gatherings that can exist alongside Baha Mar, so Bahamian art doesn’t become synonymous with the resort’s walls. “We need more than one locus of art,” he said. “We need a network.”

The stakes are high. Without alternative spaces, many of the country’s leading artists build their lives abroad. Munroe spends most of the year in Maryland; Curry lives in London. Both maintain deep ties to Nassau but rely on other cities to sustain their practice. “That’s the irony,” Curry said. “We’re showing that Bahamian art can operate at the highest level—but to do that, we’ve had to leave.”

Sales at FUZE, by most accounts, were modest. “Selling is difficult in Trinidad too,” Hadeed told me. “We share the same struggles. But it’s not about that—it’s about being here, meeting people I would have never met.” Curry agrees that the fair’s impact isn’t measured in transactions. “It’s about showing that an art ecosystem is possible,” he said. The irony, of course, is that the fair’s very generosity—the free booths, the resort’s backing—is what makes that ecosystem possible at all.

That such a project as Curry’s was approved speaks to FUZE’s paradox: a luxury resort willing to host its own critique. It is a sign of maturity perhaps—a recognition that national culture can’t grow without dissent. Still, Curry worries about access. “There are lots of people who are not going to come onto a resort property,” he said. “They don’t feel comfortable in this space.” For those who do, FUZE offers a glimpse of possibility: that a Caribbean art world might exist not just in New York or London, but here, amid the contradictions of paradise.

Amanda Coulson, founder of Nassau’s TERN Gallery and former director of the National Art Gallery of the Bahamas, sees those contradictions as the point. “It allows artists to see they’re not alone,” she said. “They can have a career and stay home. For those kids to grow up finding that normal—that’s huge.” Coulson also helped coordinate the upcoming Venice Biennale pavilion, which will pair Munroe’s work with materials left by Beadle. “Some of John’s Haitian sails will be shipped to Venice,” Munroe told me. “I’ll combine them with Junkanoo costumes left on the street after Christmas to make a site-specific work.” The sails—salvaged from migrant boats crossing from Haiti to the Bahamas—speak to the region’s intertwined histories of migration and labor. “John was disturbed by seeing Black bodies still packed onto boats by Black people,” Coulson explained. “His work was about emigration, loss, and the souls at sea. Lavar’s extending that conversation.”

Munroe describes the Biennale as a turning point. “We’re creating a blueprint,” he said. “The first pavilion was largely led by foreigners. This time it’s 100 percent Bahamian—Bahamian curator, team, production. We can do it ourselves, and we can excel at doing it.” That same ethos—self-determination built on collaboration—runs through FUZE. The fair’s power lies in its contradictions, as a corporate space creating room for critique, a tourism engine opening its doors to the local public, a commercial space facilitating regional cultural exchange on its own dime, a luxury resort functioning as a national cultural center.

Baha Mar’s motives are practical: art elevates the brand, enriches the guest experience, and diversifies tourism’s appeal. Yet the results are something deeper than marketing. In a country where state funding for the arts is minimal, the resort has become both patron and platform, absorbing the responsibilities of a ministry of culture. FUZE’s open structure—the free booths, the regional invitations, the willingness to engage criticism—suggests that hospitality can be reimagined as cultural infrastructure. Still, it raises an uncomfortable question: what happens when national identity is shaped by private enterprise?

For now, the results are remarkable. The Bahamas will arrive in Venice next year as a small island nation articulating its creative sovereignty through both public partnership and private will. On the last night of the festival, I blew $20 on a Whitney Houston themed slot machine. In the thick of the gambling thrum, I thought of that Junkanoo shack: the web of collaboration, the gangster leading his team in art dedicated to his loving mother, the shared purpose that momentarily restructures hierarchy. FUZE, too, runs on that rhythm—a collective improvisation, unexpectedly beautiful and uneasy, built from contradiction and dedication.