At Whole Festival, Russell Reed meditates on Ferropolis’s industrial scars, reimagining queer ecology and world-building

Whole Festival, the annual summer electronic music festival hosted in the forests of Germany’s industrial Ferropolis, attempts with genuine passion to serve the queer community, one that globally is both growing and splintering. Programming a festival is an intensely creative act: what are we saying through this performer? Does this bring people together? Who is this for? And, most critically, can our approach to music be for everyone?

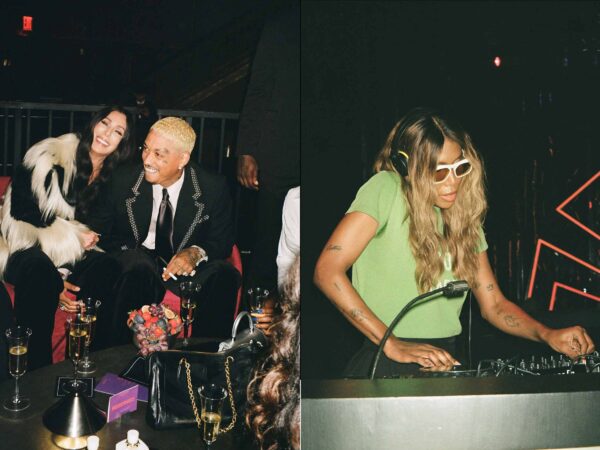

Enter After Ruin, a programming block at Whole 2025’s Ambient Stage incorporating music with live readings. Organized by London-based P. Eldridge and London-via-LA-based environmentalist Russell Howell Reed, the project investigated the festival’s ambition of queer utopia through retelling and reinterpreting the development of Ferropolis. Once a center of brown coal mining in East Germany, After Ruin tracked the site from its origins to its present, and from present to future—detailing what was and dreaming of what could be. The program opened with a reading by Reed followed by three consecutive DJ sets by music producer NM DJ, New York powerhouses Sterling Juan Diaz and Sekucci, and Berlin-based St. Mozelle, which were recently released.

The idea of Whole Festival, and its window into a story of queer identity and human impact, became a journey from ideation to action between last year’s festival to this year’s edition. Document sat down with Russell Reed before, during, and following After Ruin to understand the ideology and impact of the project. The conversations themselves mirrored the chaos of getting to (and recovering from) Whole: finding a way from Berlin to Ferropolis, stolen moments with friends, and the inevitable emotional comedown following. Reed discusses the intent of queer environmentalism, confronting festival-goers with the ideological, and the spirit of creative work.

Colin Boyle: After Ruin builds on some of the ideas that came to you in the wake of last year’s festival. Can you share your journey between then and now? What led to your decision to program a conceptual event at this year’s festival?

Russell Reed: A year later, it then made sense to bring [environmental] ideas to life at the festival, because it is so site-specific. It felt like a chance to actually activate the site, and engage with its history in real life. It was fitting to pursue this at the Ambient Stage in particular, where Sekucci’s set inspired many of the ideas I conceived last year.

Colin: [You told me last year that] you conceive of Whole as dancing not at the end of the world, but as a new future—not apocalyptic, but a rebirth. Where do you see the value of this project in the context of queer futurism? Is it an academic observation of Whole and the festival site, or do you understand it as something more active in building community?

Russell: I think it’s both. Queer people have built thriving urban club scenes, but at Whole we have this opportunity, given its isolation, to foster a level of queer expression, safety, and community-building far beyond what’s possible in cities. There’s also this very real hyper-diversification and globalization: Whole brings together all of these different global queer undergrounds, interacting and intersecting in one space. It makes these small communities we live in part of a larger project. But [my early ideas] connected to less tangible environmental theory, and re-energized me in my climate work that is often quite challenging and pessimistic.

We are now speaking during a back-to-back set of Sterling Juan Diaz and Sekucci, one of After Ruin’s three musical components. Reed sits watching the wooden stage where festivalgoers repose in front of the seated DJs. The sun begins to rise.

Colin: Can you talk a little about how this set is supposed to fit into the narrative of ecological transformation, the underlying theme of After Ruin? What is the story you aimed for Sterling Juan Diaz and Sekucci to tell?

Russell: We curated a triptych of performances, the first chapter by NM DJ engaging with the shift from the primordial into industrialization. And so where her set leaves us at this quiet—the industrial era has occurred and swiftly collapsed, and the land has been left to ruin. And now that it’s dawn, [Sekucci and Sterling] are carrying us into the next transition, waking up the land. Over the next three hours, they will take us to the present moment, after which St. Mozelle’s final set will explore what the site’s future might look like.

Colin: And what makes Sterling and Sekucci perfect for telling this moment?

Russell: Last year, Sekucci’s set was sort of the thing that brought [all my ideas] together. It resolved this tension that I was feeling as a climate activist, sitting on this site of industrial decay, but also paradoxically feeling all of this joy, community, and world building. But with Sekucci and Sterling playing together, there’s this natural interplay which I think nicely mirrors the dual acts of resistance that we’re exploring, both queer and ecological.

Colin: To what extent were your prompts to the musical artists open to interpretation? How much guidance did you give them?

Russell: The prompts were super open. We mapped out the site history into three chapters, invited DJs to respond to each, and that was basically where we left it, so it was not super hands-on. We wanted to select people we really trusted and prompt them to engage with the ecological concepts themselves.

Colin: It feels like we’re at this moment of thinking about what the legacy of Ferropolis is. To me it just feels like a negative legacy of industrialization, but there’s also the chance to build something new.

Russell: I think it’s hypothetically true that if we were to just zap every human off the face of the earth right now, ecosystems would rebuild. Their resilience is remarkable. We’ve done a lot of damage, but I don’t hold this negative view of humanity—it’s very old school. It’s this kind of misanthropic environmentalism that considers humans inherently flawed, when the real rot occurs in the violent power and knowledge hierarchies that separate us. It’s an act of faith to say that humanity isn’t so broken. I see this time of rupture and collapse as a call to look outside the normative bubble and to surface the knowledge that has been erased and undermined in the industrial regime. What does it look like to unearth other ways of being human, recognizing the downright failure of the present?

Colin: How can we do all of that here? Whole Festival is only four days long. What is the long-term impact of something like After Ruin?

Russell: I think we’re really fixated on the systemic and the scalar. We don’t give enough credit and power to what happens on this very intimate, human, and relational level. Thinking about what Whole has meant to me, this being my third year, it has been a place that has unlocked all of these components of my identity that have changed the way I see myself, my practice, my work, and the world. It seeded in me new frameworks and ways of thinking, and, honestly, a sense of hope that can only come from seeing firsthand what kinds of worlds can be built. It allows you to think differently about how you go about your day, and in that way its impact multiplies.

It’s now two weeks following the festival. From Fire Island, I call Reed at his family home in California, which is also a turtle sanctuary. We examine After Ruin in hindsight.

Colin: You mentioned over text that viral Fran Lebowitz quote [from the documentary Public Speaking (2010)] about audiences and artists lost to AIDS. I would love for you to recapture the spirit of that and tell me why that occurred to you in the first place, especially in relation to After Ruin.

Russell: I think there’s a big interest right now, and I guess there kind of always has been, in discussing the devastation and the injustice of HIV/AIDS. But something Fran prompts me to think about is not only what was lost, but what therefore must be regained. She expresses that the devastation of the epidemic was particularly strong among cultural actors and audiences—people who were having a lot of sex, basically. It makes sense, then, that in its wake we see a movement that is a lot gayer than it is queer, and a lot more focused on normative paths to integration. That is the world that I grew up in, so as a teenager I always thought we were pushing for integration and rights and a seat at the table. It has taken me years, as a cis white gay guy benefitting greatly from that fight for integration, to realize that I don’t want a seat at that table at all. What you realize is that the power of queerness is intervention, that I would actually rather flip the table over completely. In After Ruin, I felt myself begin to pick up on the threads of a more radical way of being queer, one we risked losing completely through the necropolitics of HIV/AIDS.

Colin: What are we building this culture in opposition to? What is still genuinely subversive in a world where we have come quite a long way as a community? What do you feel like is a real act of queer subversion in what we’re building now?

Russell: It’s not necessarily either/or. There is no denying that the conditions that make something like Whole Festival possible, that allow thousands of queer people from around the world to gather in one place, are in part the result of that rights-based queer politics. What is important is that we reap the benefits of that progress, while also recognizing that our world system remains intolerably violent and destructive, especially for queer people. As the climate crisis accelerates and political and economic infrastructure crumbles, I think we are arriving at a moment of recognition that things must be done differently. And that is a prompt for us to consider whether we can engage in proactive world-building that doesn’t only occur at the fringes, but could represent a new way of living on Earth.

Colin: This is also the first time that you are programming something musical, what did you learn from doing it, from seeing it in action? Now, in hindsight what would you have done differently, and how would you approach something like this the next time? Do you view it as successful in imagining a queer ecological utopia?

Russell: Working in more traditional environmental roles, I have become accustomed to certain rules and frameworks—in laboratories or conservation sites or even multilateral political negotiations, there are many agreed-upon frameworks that are based in science and “fact.” My desire to engage in cultural practices, to work directly with artists and foster new forms of engagement with nature, is to challenge that scientific imperialism and to give platform to non-scientific environmental knowledge. That is easier said than done, and After Ruin was a huge learning experience. It required a lot of trust to allow each artist to respond in their own way and to produce, in sum, a cohesive story, but I think the diversity of musical approaches and interpretations made the program especially effective.

Colin: I think [live music is] also really different from navigating institutions, institutional politics, or academic politics, or any of these things that you have previous experience with.

Russell: Yeah, totally. And I was lucky that I was working with people who I really believe in and trust, who respond to the energy of the room and cultivate a space that is critical to the experience of Whole—the Ambient Stage fosters reflection in the often overstimulating, high-tempo universe of the festival. And so working these themes in, while also being very responsive to the audience and environment, is a huge part of the point. I think that’s another thing that I found to be both a challenge and a core opportunity of the program.

Executing place-based work in the flow of a festival is crazy, and navigating my own stamina, schedule, and presence was demanding. And there we were at 4 a.m., having this conversation in the middle of the programming, and I thought, ‘What business do we have doing this right now?’ But I ended up leaving our conversation with such a different experience of the whole thing, because I was reflecting on the program while actually witnessing it and participating in it as audience. And that was super special. It felt like a big success in ways that will never be measurable. I think it will continue to expand what people think can be done at a festival, and how people can approach these spaces through a lens of care and with an eye toward lasting impact.