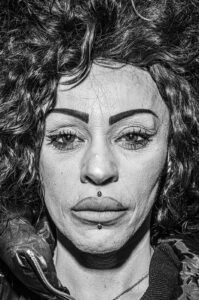

The Magnum photographer’s latest body of work, currently on view at the Leica Store & Gallery, is a striking signature snapshot of eight days in Naples

Eight days is not long enough to capture the true character of a city, let alone scratch the surface, but if there’s one photographer that can rise to this challenge, it’s Bruce Gilden. This past winter, the renowned Magnum street photographer took his Leica camera to the streets of Naples, Italy for the city’s annual Feast of the Epiphany, or La Befana, which takes place each year on January 6th, marking the end of the Christmas season. The result is 8 Days in Napoli, a captivating and comprehensive series of images—currently on view at the Leica Store & Gallery through November 2nd, and an accompanying photobook marking the inaugural edition of the Leica Libretto series.

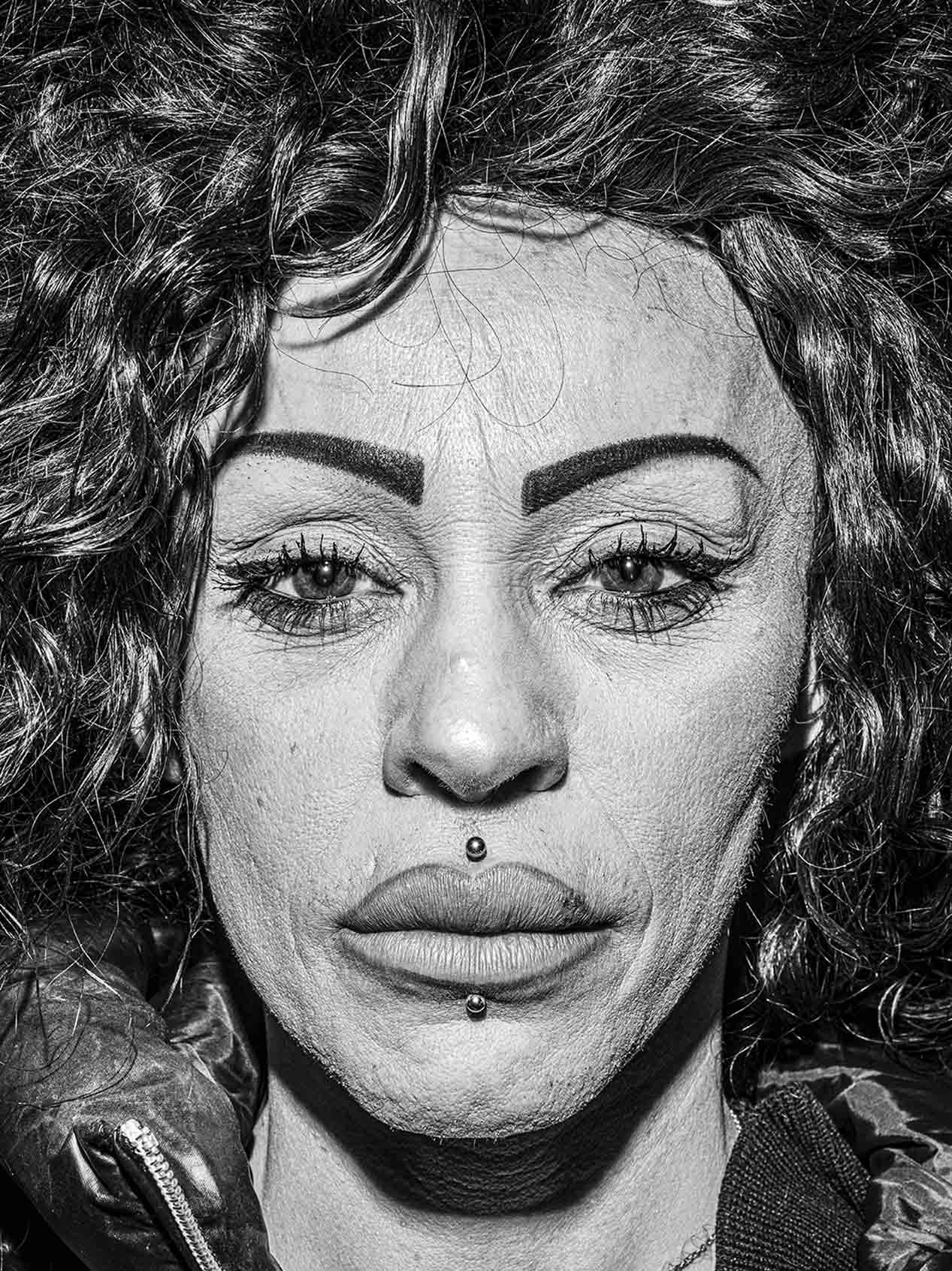

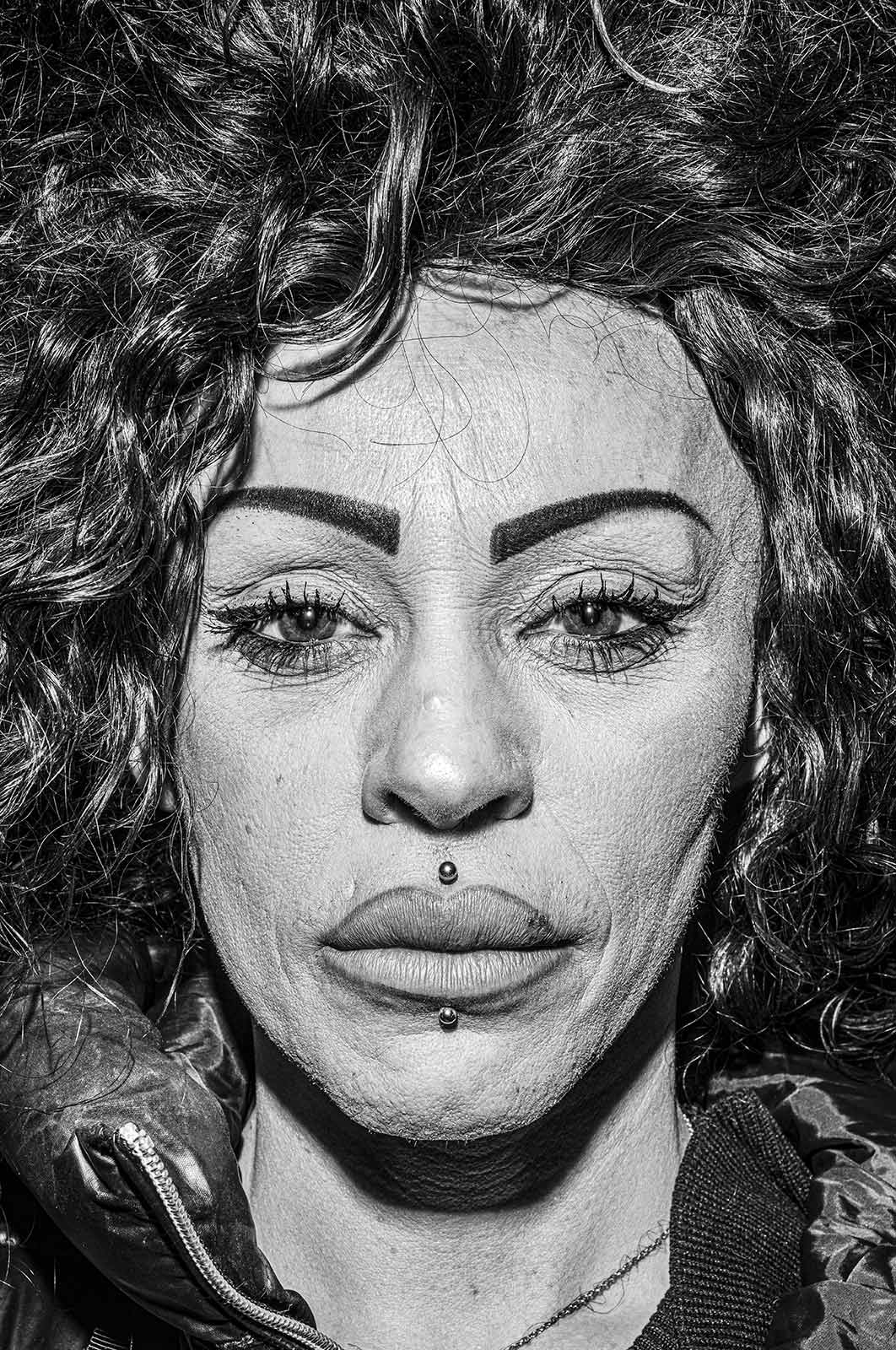

Gilden’s gritty, self-taught style of street photography captures things as they are, not how we want them to be. His stark lens doesn’t shy away from the strange or grotesque, often documenting subjects that are swollen, bruised, bandaged, or teary-eyed. In many ways, his unflinching eye is the perfect match for Italy, the country that gave rise to the neorealist film movement, and embraces strife with a sense of romance and wit. Several of the portraits in 8 Days in Napoli evoke Anna Magnani’s perfect face of defeat in Mamma Roma, or Lamberto Maggiorani’s dramatic despair as Antonio Ricci in Bicycle Thieves. And similar to De Sica and Rosselini, Gilden’s neorealismo holds a rawness missing in many aspects of our social media-saturated lives, one that makes it hard to look away.

Much like his photographs, Gilden himself is steadfast and acerbic. Since we were both raised in New York, this demeanor is familiar, comforting, even. As we chat over zoom, his nods in agreement somehow still feel like a confrontation. This tension is reflected in his photographs, where his camera’s close proximity and bright flash is met with grimaces, frowns, and direct stares that shatter the fourth wall. Just as Gilden dares to take the picture, his subjects dare to look back.

But how close is too close? The fragile intimacy of Gilden’s portraits sounds alarms among viewers around questions of ethics and consent. To Gilden, these questions are “irrelevant.” He shares that he’s asked consent of almost every person he’s photographed, and it’s often the onlookers, or those not in the foreground, who have something to say about what he’s doing. It’s also impossible to scrutinize Gilden’s approach without acknowledging the fact that we live in a highly-surveilled society of gadgets like Meta Glasses, where we are constantly on camera, and often unknowingly. “They say beauty is in the eyes of the beholder,” Gilden points out, “It’s the same thing with distance.”

As the Leica exhibition comes to a close, Document sat down with Gilden to discuss the process and inspirations behind his eccentric craft, the theater of cities, and 8 Days in Napoli.

Anabel Gullo: I’ve read that your practice is largely self-taught. How did you first get into photography?

Bruce Gilden: I’m basically self taught. I was at university, and there was really nothing I was studying that I thought I’d want to pursue later on in life. I liked films, so I figured I’d try acting. And since photography in the late ‘60s was very much up in the air, I took a photography course. Once I saw that I’d done something in life for myself besides playing sports, I looked at the image that I made and I said, ‘Holy crow, this is what I want to do.’

I started out by looking at books. I had no orientation photographically before this. A quote by Robert Capa struck me, ‘If it’s not good enough, you’re not close enough.’ And it’s interesting, because when I read that quote, I’d only been taking pictures for a couple of weeks or a month. And now I realize why it struck me, because I [originally] wanted to be a boxer. Whenever I fought, I fought close. In all sports I did, I was very physical and I was always in tight. So it carried over to my photography. I looked at many books, and went to many exhibits. I saw what I liked and what I didn’t like. I tried to figure out what lens they used, where they stood. I stayed with it, and then I really became Bruce Gilden.

Anabel: Since you mentioned that quote from Robert Capa, how do you know when something is good enough in terms of your own work?

Bruce: You could look at the contact sheet or the image for 100 years, it’s not going to change. If it jumps off the page, you know it right away. That’s an interesting question from the viewpoint of Lost and Found, the book I did with my early New York pictures. There are some pictures that I think are pretty good, and I didn’t put them in my first New York book. My style grew into more who I was to become and who I am. I won’t say I missed those pictures, some were quite good, but they didn’t have the drama. Everybody’s opinion of what a good photograph is different, but I trust my judgment.

“In the beginning, you’re still learning your craft, but if you continue along that road, you can—if you have a self, or an interesting self—become that self, but you have to be strong enough to go through all the bullshit.”

Anabel: Drama is an interesting word that you use, because I feel like there’s definitely a theatrical element to your latest series, 8 Days in Napoli, which leads to my next question. Your pictures are unmistakably yours, they’re distinct even down the texture. This recent series is no different. Could you speak a bit about the process of refining this style from your early days?

Bruce: A smart photographer and teacher once told me it takes 10 years to become a photographer, I don’t know if that’s true. But I looked and I learned, and I became myself. In the beginning, you’re still learning your craft, but if you continue along that road, then you can—if you have a self, or an interesting self—become that self, but you have to be strong enough to go through all the bullshit. And then you take a little from here, a little from there. Like my good friend Martin Parr said, ‘We all steal, some of us get caught.’

Anabel: Is there anyone in particular that really influenced you?

Bruce: I liked Lisette Model. I liked [Shōmei] Tōmatsu, I liked William Klein…there are others too. But when I give workshops, the title of the workshop is, ‘Be Yourself.’ I try to see who the person I’m teaching is. It’s more like a psychology course. And then we go from there, because everybody isn’t me and I’m not them.

Anabel: On the more technological side, could you speak a bit about your collaboration with Leica and the roles that their cameras have played in your work and style?

Bruce: When I started photography, I started with a camera called a Miranda, which was a cheaper Japanese camera. Then I bought a Nikon, and I used a Nikon from, let’s say, 1968 to ’77. Since I liked people like [Gary] Winogrand, and he used a Leica, I said, let me use a Leica. Since then, it’s been my camera of choice.

And it’s funny, because the earlier Leica film models, since they were rangefinder, had a lot of minuses. The sync speed on flash was very slow, so you couldn’t really use flash in the daytime. But I loved how it felt in my hand, so I stayed with it. Years later, somewhere in the early 2000s, I had a job in France, and I had a couple of Nikon film cameras. So I took one with me, but it was so inhibiting to me that I just said to hell with it. Because for me, the Nikon is almost like being in a small room or a box where the form is beautiful, but it doesn’t allow you to have that extra breath that the Leica allows you to have.

Anabel: What was the experience like of shooting in Naples? How did this series differ from your past work, and what are the different considerations or practices that you have when you’re shooting in a different country that’s not your home?

Bruce: Every country has its own heartbeat, so before I go to a country, or before I start a project, there’s a little thought that goes into it. I also always like [to photograph] people that are not in the mainstream of life, because I’m an outlier. Before I started my project on bikers, I said I was going to do it in color. And there were no faces, that’s not how I envisioned the project. It’s the same thing with Naples. I already knew that I was going to do it mostly candid, and with some faces. The faces could be color or black and white, depending on which was stronger, and the candid pictures, which is most of the project, would be in black and white. I chose that because, to me, Italy is a black and white country. It’s very traditional, it has a strong religious background, and the black and white movies of De Sica, Rossellini, Anna Magnani…I don’t see it in color.

So before I start any project, I decide whether I want to do it in black and white or color, which camera I want to use, and then I go forward and I can’t recall a time where I’ve changed my mind midstream. I have a thought of what I’m going to do, but it doesn’t always work out that way. So you have to be smart enough to realize, ‘okay, that’s not working. So what do you have here? And how are we going to deal with that?’ And when you start going to a place, I think it’s very important to go to different areas. What’s interesting is, some areas are good in the morning, other areas are good in the afternoon, other areas are good at night.

Anabel: And by ‘good,’ do you mean an abundance of people, of photographic material?

Bruce: Yeah. And I found that most of the places are only good in short bursts. I’d love to go back to Naples because I think I only touched the surface. In Naples, January 6th is a big holiday. We arrived on the fifth and went out that night to a place where the lady who was helping us took us and I took some pictures that were okay—two or three of those are in the book. But I was jet-lagged and I asked the lady how the sixth would be for photography, to which she replied it would be great. There was nobody out on the sixth. I left at one in the morning on the fifth, and I was so pissed off because I should have stayed till four in the morning on the fifth, because everybody was out. So you live and you learn.

Anabel: How do you handle questions, concerns, or assumptions around subjects’ consent or autonomy in your work?

Bruce: To me, I’m comfortable. How do you know what somebody likes is what somebody doesn’t like? I’ve found that a lot of people that you think would be suspect to say yes to being photographed love it, and sometimes people who you think wouldn’t mind have a fit.

They say beauty is in the eyes of the beholder. It’s the same thing with distance. You know, certain people give you credit for being upfront and honest, and other people may not like it, just like someone you can take a picture of someone 30 feet away, and someone will like it, and someone will say, What are you doing? Like Josef Koudelka once said to me, do you walk in my shoes? All my face pictures, I should say, I’ve asked permission of the people. And there are a couple of times I can recall where someone came over and asked the person why they allowed me to take their picture. That’s why I stay alone a lot…

Anabel: Do you think it’s necessary to be physically close to someone to know or understand them?

Bruce: That’s up to the individual. There are pictures that can be taken from a mile away that are wonderful. It’s not about the proximity. I’m comfortable with being close. Sometimes I’m so close, people don’t even realize I’m taking their picture. With flash, it’s a little bit more obvious. For example, in one of my well-known pictures on the beach in Coney Island where the lady is pointing in a bathing suit, I was on my knees to take the picture, and I took a few snaps, and then all of a sudden a guy came over and said to her, what is he taking a picture of? She didn’t realize I was taking her picture. It’s not always about how close you are, it’s how comfortable you are and how comfortable you make people feel. Being a relatively good athlete, I was very agile, so my movements were quite natural. It’s how you carry yourself. A lot of people have a problem with it, but when you’re far away, you’re a real sneak.