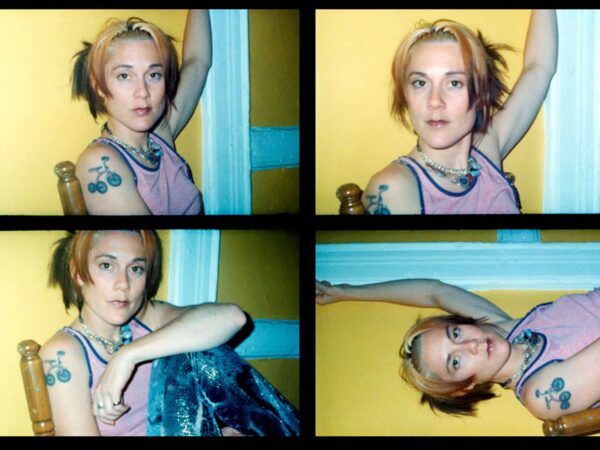

Canadian multihyphenate artist Bambii returns to her Infinity Club with unfinished business

These days everyone wants to be a party girl. Kirsten Azan, however, is a rare original. Performing as Bambii, she has shaped some of the rave scene’s defining recent projects, co-producing much of Kelela’s Raven and featuring on Shygirl’s Club Shy Room 2. Her debut EP, Infinity Club, pulled a striking range of collaborators with the confidence of a seasoned host and selector. We catch up on the heels of her Glastonbury debut, just days after the release of her sophomore EP, Infinity Club II. Despite the critical success of its first chapter, she returns to the project steadfast in her Sisyphean commitment to measuring infinity.

A lot has changed in the two years between. Namely, pop culture has taken heightened interest in the underground electronic music scene, resulting in a seemingly endless propagation of label-backed rave projects and corporate-sponsored raves. We’ve seen the good, the bad, and the ugly, though we agree not to name names—here, at least. Bambii puts it plainly: “They want to sound like the rave, but I know they’ve never been to the rave.”

“When I think of club culture as depicted in pop right now, it’s being captured at large,” she continues. “The aesthetics, the ripped clothes, the drugs, the sex. But it’s obvious when you have no queer friends, no trans friends, when you’re just not about that life.”

Any pop appropriation of a subculture is bound to lose some texture. But in the case of electronic music, created and upheld by Black, Latino, and queer communities too often overlooked by the mainstream, the whole is categorically dissimilar from the sum of its most easily aestheticized parts. This so-called underground exists not beneath hegemony, but in opposition to it, and top-down interpretations are therefore doomed to miss the mark. “They’re not counterculture,” Bambii states. “They’re not counter-anything.”

She speaks with the authority of a veteran club kid, having founded JERK, the Toronto underground’s enduring paragon, over a decade ago. Back then, she was a college dropout who couldn’t keep a job. She laughs as she estimates she’s been fired “like 600 times.” But she was clocking impressive hours at the function. Toronto is among the world’s most multicultural cities, but in the early 2010s it was dominated by an overwhelmingly white alt rock scene. Countless other music cultures could be found across the city, but they rarely met, each diasporic sound confined to a single neighborhood. JERK was Bambii’s attempt to collapse those boundaries—and to book herself as an amateur DJ that no one else would.

The party sold out in an hour, and it’s been selling out ever since. It was the first time she “felt held by something,” a feeling that would soon set the direction of her life. And she wasn’t alone. From the start, Bambii filled a crucial gap in the city’s music scene, giving Toronto the truly multicultural rave it had lacked. The formula is twofold: she invites an eclectic mix of selectors from the city, while carefully chosen international bookings provide even further reach. Holding such range in one room requires trust. She earns it by consistently unearthing the intrinsic harmony between seemingly disparate sounds, no matter the distance between them.

“Like if we took a CAT scan of everyone’s brain in that club, we’d see the same image… I don’t know if it is magic or science, but that is the Infinity Club to me.”

Her own sets celebrate the diverse Black roots of electronic music—not just Chicago house, but also dancehall, funk, jungle, and reggaeton, to name a few. By threading such manifold music lineages into individual sets, she curates atmospheres that are historically rich yet sensorially new, a patchwork only possible in a highly globalized world. “I’m working out the sonic connections between all the music I listen to,” she explains, “and then bringing it all together.”

Bambii recently self-diagnosed with maladaptive fantasy, so it is fitting that Infinity Club came to her in a daydream. Her debut EP is an exploration of the transformative potential of a club night, colored by a professed obsession with science fiction. Any good scifi evokes a suspension of disbelief, when the viewer fully accepts the surreal logic of its imagined world. Infinity Club relies on the same condition: on the dance floor, time and space contort until the boundaries of self dissolve into a single collective: “Like if we took a CAT scan of everyone’s brain in that club, we’d see the same image.”

“I don’t know if it is magic or science, but that is the Infinity Club to me,” Bambii explains. “A mythical space where people transcend their physical forms to become the people they see themselves to be.”

In Infinity Club II, Bambii captures that mythos with refined clarity. Over just 24 minutes, she collapses the many hyphens of her artistic identity—selector, producer, vocalist—while reaping the benefits of her renewed studies in piano and bass. The record spans an almost impossible range of sound with unshaking confidence, never losing its coherence despite a crowded set of collaborators. This feat is captured at the outset with “Remember” as Ravyn Lenae’s ethereal melody and Scrufizzer’s cutting grime flow unite over a canvas of skittering drums. It is a project only Bambii could produce, grounded in a fanatical knowledge of Black music history and a singular ear for unexpected synergies.

“They’re not counterculture. They’re not counter-anything.”

In a sea of pop appropriations, Bambii proves the irreplicable distinction of an authentic rave project. She inverts their directional logic, exploring instead whether the spirit of the underground can scale beyond the fleeting timespace of the club. Despite its referential depth, Infinity Club II feels futuristic, welcoming listeners to a fantastical world where multiculturalism is taken to its logical extreme. Bambii’s infinity is a pulsing collective accessed not by the abandonment of individual identities, but through their careful immersion. At a time of escalating tribalism, Infinity Club II proves the persistent possibility of transcendent unity.

Many write off rave culture’s resurgence as escapism, a way to temporarily depart a world in rupture. In a sense, that is precisely what the underground has always provided—a sanctuary for those who find themselves outside the confines of an ever-tighter cultural hegemony. But is this infinity simply a privileged fantasy wasted on the young, beautiful, and urban? Or is it a future unfolding, a declaration of what reality is meant to be?

“Infinity Club is about real life,” she clarifies. “That’s what I’m trying to get back to. Bad things exist because people decided they would, but a lot of good things exist because people decided that, too.”