Leigh Bowery's art was inseparable from his presence—a challenge Tate Modern's retrospective can't quite solve

Leigh Bowery landed in London in October 1980, cherub-faced and freshly dropped out of fashion school at just 19 years old. By New Year’s Eve, his resolutions were set: he’d lose weight, wear makeup every day, absorb everything, and break into art, fashion, or literature. Soon, hardly anyone would remember he came from Sunshine, a Melbourne suburb that sounds more likely to export postcards than provocateurs. Born anew, he found his way into nightlife—and into a crowd that spoke his language. His new friends helped translate his singularity into a currency of wild looks and wilder instincts. Being too much wasn’t just welcome, it was the whole point; something to aspire to and find solace in, even now, 30 years after his death from complications of AIDS. But his legacy isn’t some cloying conceit about authenticity. As his ongoing retrospective Leigh Bowery! at Tate Modern makes clear, Bowery embodied artifice, but never deceit. What he made up, he meant.

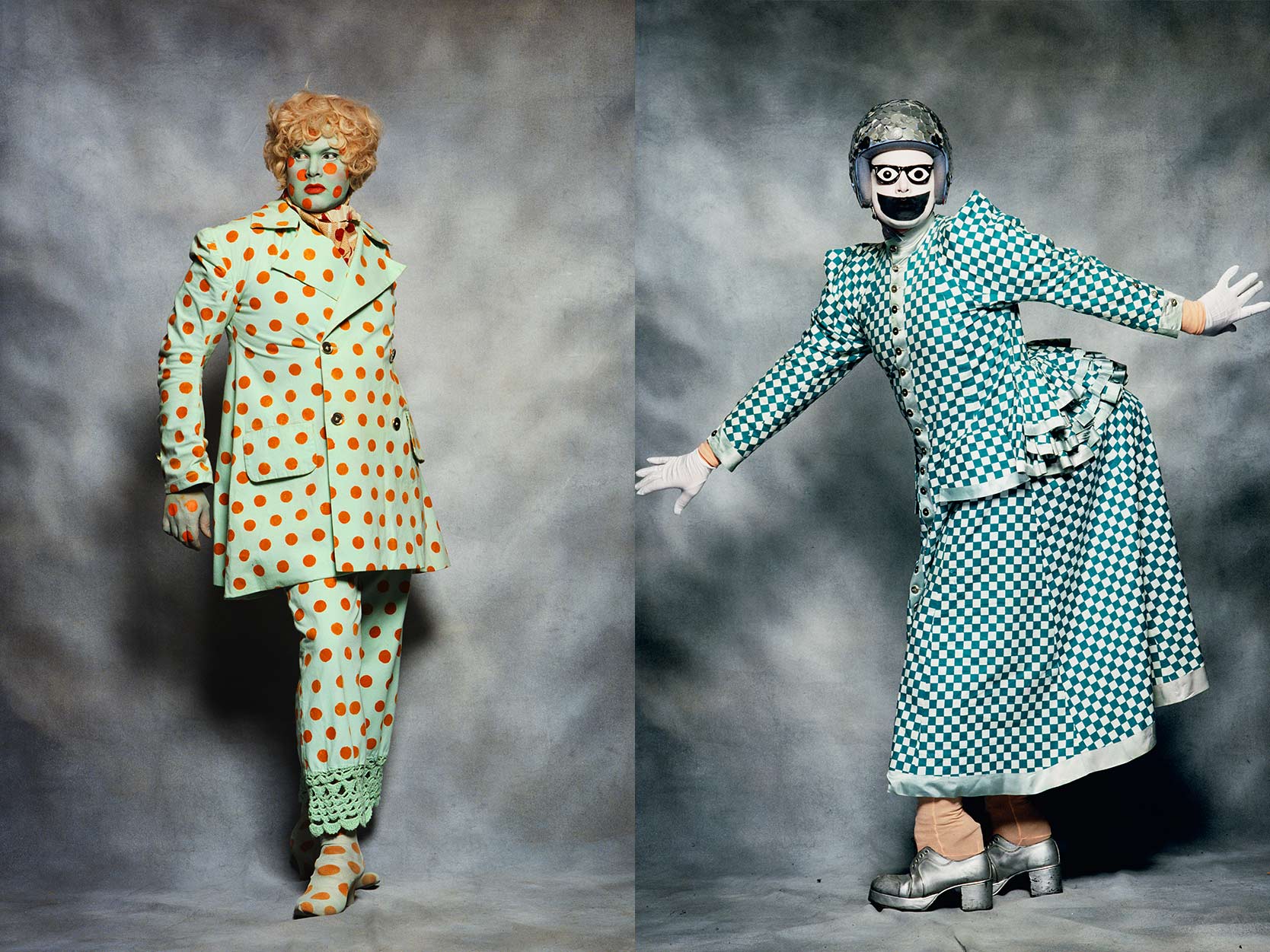

At first, he played by fashion’s rules, staging four collections between 1982 and 1986 in London and abroad. One was titled Pakis from Outer Space. It was a different time, as people say. The look included platform boots, body paint, piercings, plus all the vaguely ethnic flair a Brick Lane fabric shop could muster. A glam-rock Kali, if you will. Next came Mincing Queens, which imagined what a “rent boy” might look like in his mother’s eyes. It looked as if Baby Jane Hudson had raided a Puritan’s wardrobe and let Picasso do her makeup. At Bowery’s side was Trojan—his unrequited love, a lithe boy with delicate features who once hacked off half his own ear and then lipsticked the stump. They’d drop acid and go out dressed in Bowery’s creations. First to Heaven nightclub and Wardour Street dives, then to Taboo, the notorious party he launched with promoter Tony Gordon in 1985. Dance floors soon replaced catwalks as fashion became “really boring and quite dirty,” Bowery griped. By that point, he’d also traded pastiche for a kind of tunnel vision. Head-to-toe sequins, each one hand-stitched. He pictured a “boob tube tutu” and piled on tulle until it became a fluff ball. One zit prompted a faceful of fake scabs.

When punk became a style, Bowery reminded us it was a stance. And yet, looking back, his aesthetics felt less like a middle finger to decorum than a wink in its direction. Take his 1988 appearance on BBC’s The Clothes Show, where he pranced into Harrods’s tea room, announcing, “The staff here adore me.” In a mock-posh accent, he fibbed about visiting as a child, with his fingers fanned and one leg prissily pointed as he spoke. These flourishes held meaning. They deepened his playacting at good taste—Royals, Laura Ashley florals, and Tatler pages—and drained it of all elegance. At Leigh Bowery!, his clothes are shown on mannequins, and the joke falls flat. Worse still, these are replicas, stripped not just of context but of attitude. That’s not to say this kind of recontextualization never works (for example, Robert Mapplethorpe’s show at Gladstone 64 last March, where the hush of an Upper East Side salon made the photographer’s work feel all the more perverse). This exhibition, by contrast, draws out a clownish quality in Bowery’s clothes, one that may have been present but was always offset by something darker, more confrontational or severe. Such is the trap of institutional display, and the fate of those clothes. Bowery once threw his garments out the window to photograph them as limp puddles on the street below. Without him, they’re just clothes. Big and bold, yes, but somehow missing the point.

His point was simple—simplistic, even: to make people squirm, laugh, stare. Then to push even further. That was his art. But if you accept and even celebrate that: how far is too far? And who gets to decide? The curators chose to leave out images of Bowery’s most contentious moments, including the blackface minstrelsy, the dominatrix Nazi act, and the Hitler quilt made from rags he pilfered from Lucian Freud’s studio—Freud being Jewish, no less. The result is an exhibition that makes transgression safe for viewing. The curators, to their credit, flagged certain moments as points for questioning, though they largely sidestepped specifics. They’re afraid of making viewers uncomfortable—and of that discomfort reflecting poorly on Bowery’s image, or more subconsciously, on their own choice to celebrate it despite its perceived blemishes. But reducing these transgressions to blind spots or blunders misses their deep connection to why Bowery remains compelling. And then, hailing his provocations as radical only compounds the oversight. This absence of friction creates a false sense of daring, one that confuses shock for progress, and boundary-pushing for genuine challenge. Bowery wasn’t out to start a revolt—just some trouble.

As the ’90s dawned, his looks grew more extreme. Foam and corsetry sculpted WWII pinup curves and alien limbs onto his frame. Above it all, a British “bobby” helmet sported a cock-shaped coxcomb. A mask bore a hairy vulva. On stage, his shock tactics escalated, too. Hanging upside down, he bore the bite of clothespins fixed to his nipples and penis. He “gave birth” to his wife Nicola Rainbird, who crawled out from beneath his costume, naked and drenched in fake blood. At an AIDS benefit, he sprayed the audience with water from his anus. Police were called. The club nearly lost its license. Bowery almost regretted it, but instead, he posed as a student and mailed a defense, proclaiming himself an original whose genius demanded praise, not punishment.

His arrogance was unmistakable. For one thing, rejection to him wasn’t a verdict; it was a misjudgment. For another, he saw himself not just as artist, but as muse and engine fueling others’ rise to greatness. But that arrogance doubled as a shield against his fragile humanity. Bowery once brought his family to a Melbourne show he’d staged with Michael Clark’s dance company—then watched in horror as Clark let every mimed sex scene play out, dildo included. What his mother imagined as “the pièce de résistance of a triumphant homecoming turned out to be the most mortifying experience of her life,” Bowery wrote to his friend Sue Tilley. “Which explains why I’m typing a ten-thousand-word essay in my bedroom while she’s crying her heart out.” In his letters to Tilley, sex came up constantly. Then loneliness. But just as quickly, something caustic and ridiculous, like a splash of cold water to the face: “The major downside of success and applause is that I freak out and have to be mean to you.”

That unflappable self-importance remains a defining force among many gay men. We leave home—and with it, the expectations of who we’re meant to be. We tell ourselves we take up more space, feel more deeply, move with more purpose. We head to the clubs hoping to be seen—only to queue for hours, pay too much for watered-down drinks, strip off our shirts just to disappear into the crowd. Sometimes we go home alone, because what makes us harder to hurt also makes us harder to hold. Then we learn to romanticize the heartbreak. And do it again. And again. Until we turn sadness into something we can shape, sharpen, and call our own. Bowery knew this well. His vulnerability was as much performance as emotional truth. It shows in Freud’s penetrating portraits of him, and in a video by the filmmaker Charles Atlas, Teach (1992)—the best, most delirious piece in the retrospective. In it, Bowery lip-syncs to Aretha Franklin through plastic lips bought at a gag shop. He stares down the lens as she sings, her voice scolding almost, “Take a look in the mirror / Look at yourself / But don’t you look too close,” as if cracking a joke only we understand about this pathetic, pitiless, and beautiful act of living.

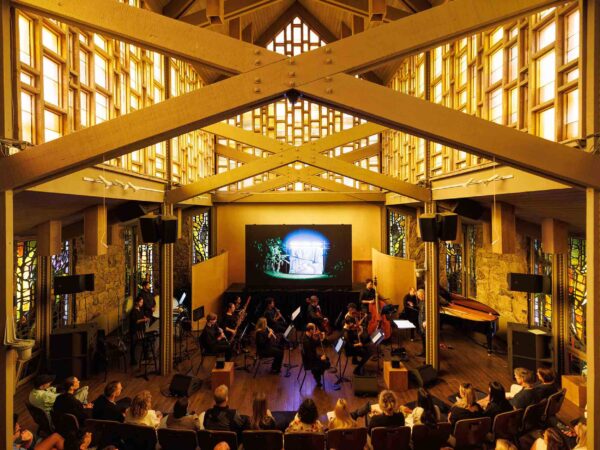

Leigh Bowery! is on view at Tate Modern through August 31.