From founding a Gowanus squat to performing at MoMA PS1, the transdisciplinary artist has carved a path from New York's margins to its cultural center without losing his edge

As a kid growing up in downtown Brooklyn, Ellery Neon was always up to no good. Born to a Lithuanian poet father and a New York-native visual artist mother, his artistic journey unspools like a punk odyssey—from teenage graffiti tagger to squat founder, train-hopping wanderer to drag wrestling impresario.

“The world is both beautiful and heinous at the same time,” Ellery reflects, a philosophy that permeates every aspect of his multifaceted practice.

His story begins in the early 2000s Brooklyn punk scene, where he cut his teeth as a graffiti tagger with his signature “You Go Girl”—a deliberately queer statement which eventually evolved into Hugo Gyrl, his artist pseudonym since 2015. His designs were heavily influenced by comic books superheroes, anatomies with twisted proportions and puffy bulging muscles. “If you’re [in Brooklyn] and you’re a kid, it’s just kind of something people do,” he explains. “Growing up in the graff scene, it was very much like a straight boys club. I always felt a little bit on the outside. So I wanted to write something that was funny and made people happy, and was a little femme and queer. I added witch hands and a lot of other motifs that were a little darker because I didn’t want to just seem like a fucking ‘live, laugh, love’ bath mat from Joanne’s Fabrics.”

He continued with graffiti after leaving his family home at just 16, but it was his discovery of an abandoned red brick power plant on the banks of the Gowanus Canal a year later that would cement his place in New York’s underground history.

The building, which Ellery dubbed “Batcave,” became home to a squat community of up to 15 residents at a time. “We stole electricity from different lampposts and even [from] a drop drawbridge that goes over the Gowanus Canal,” Ellery recalls. “When the drawbridge would go up, we would lose power. It was kind of charming.”

Batcave thrived for years, hosting raves, punk shows, and a bicycle repair shop, maintaining a strict no-hard-drugs policy. But when too many core residents left to travel—including Ellery, whose train-hopping voyage eventually led to his settling in New Orleans for many years—the community deteriorated. “When I came back, people who were in the building had started using heroin and the whole place had fallen to shit.”

Rather than abandon the space entirely, Ellery’s relationship with it evolved, returning periodically between 2008 and 2012 to scribble massive political messages across the building’s roof. The first, painted after the 2008 financial crisis, declared: “Open your eyes! No more corporate bullshit! Fuck Wall St!” Another, in 2012, read: “End stop and frisk! Hands off the kids!”

His political scrawls caught the eye of an arts philanthropist who then purchased the building. “He told me that he bought the building because he was attracted to the graffiti that I’d been painting on it, and he wanted to keep the radical energy of that spirit alive,” Ellery explains. The former squat was converted into Powerhouse Arts, a not-for-profit cultural center. Designed by architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron, who had previously converted yet another abandoned power plant into London’s Tate Modern, the architects preserved Ellery’s original graffiti throughout the space, even commissioning him to design the lobby’s central mural in 2023.

“That’s been kind of a recurring theme of my life,” Ellery notes, “making art without being aware of the repercussions it’s going to have for other people or in the world.”

This dynamic struck again in 2024 when, following the aftermath of October 7, Ellery updated a mural he had painted on a nondescript concrete wall surrounding a cell tower New Orleans’s Tremé neighborhood. In February of that year, he reinvented the mural to depict a green-skinned figure with Palestinian flags in her eyes and the text “All Eyes on Gaza.”

The mural stood untouched for months until an irate man was caught on camera defacing it, attacking Ellery’s work as “Hamas propaganda”. The confrontation went viral, drawing both gushing support and ire. When the mural was eventually buffed entirely, community members continued repainting their own political messages on the wall.

“I got to create a space that is specifically for one message. And I don’t care if it’s my work at this point—it doesn’t matter. It’s just beautiful that it’s getting this message out,” Ellery said.

While Ellery’s street art tackles political realities head-on, his alter-ego Gorlëënyah—a triple-nosed green alien wench who looks like she sprung from one of his murals—takes a more tongue-in-cheek approach. She’s the host of Choke Hole, a drag wrestling spectacle founded as an entirely illegal performance in New Orleans in 2018. Think WWE with its queer subtext amped all the way up: drag performers fly-kicking each other in the face and squashing opponents with giant boots, vapes, and baby bottles carved from styrofoam—skills Ellery honed creating Mardi Gras floats.

“All wrestling is real. It’s choreographed, and very dangerous,” Ellery asserts of the sport that has taken him from warehouse spaces in New Orleans to theaters and museums in Las Vegas, LA, and Germany. The elaborate production involves live lip-sync performances, fierce acrobatics, and custom videos that play before each match to establish character drama and. The troupe features a rotating cast of seedy characters with elaborate backstories. Jassy is an evil hyper-capitalist landlord who owns 99.9% of earth’s land, while Vis Queen serves as Gorlëënyah’s semi-automatic sex-robot head-of-security with a gun for a leg. Jocelyn Change, a white hippie police officer with dreadlocks who confiscates your drugs so she can do them herself is the troupe’s most detested character.

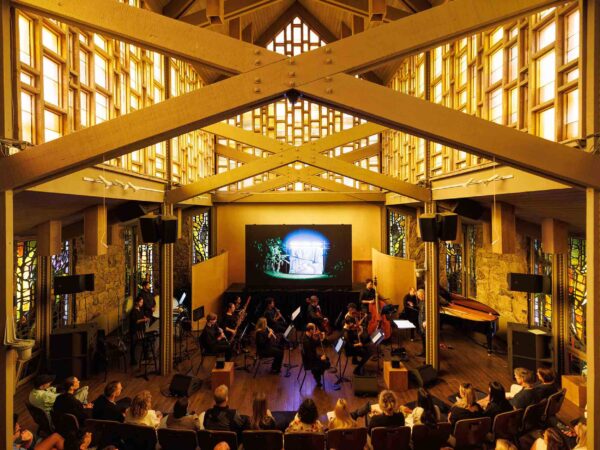

Returning to New York, with previous performances held at Times Square and The Met among others, Choke Hole will be staged at MoMA PS1 on June 13 as part of a fundraiser for Visual AIDS, dragging one of New York’s most prestigious art institutions into the subversive world of debaucherous wrestling.

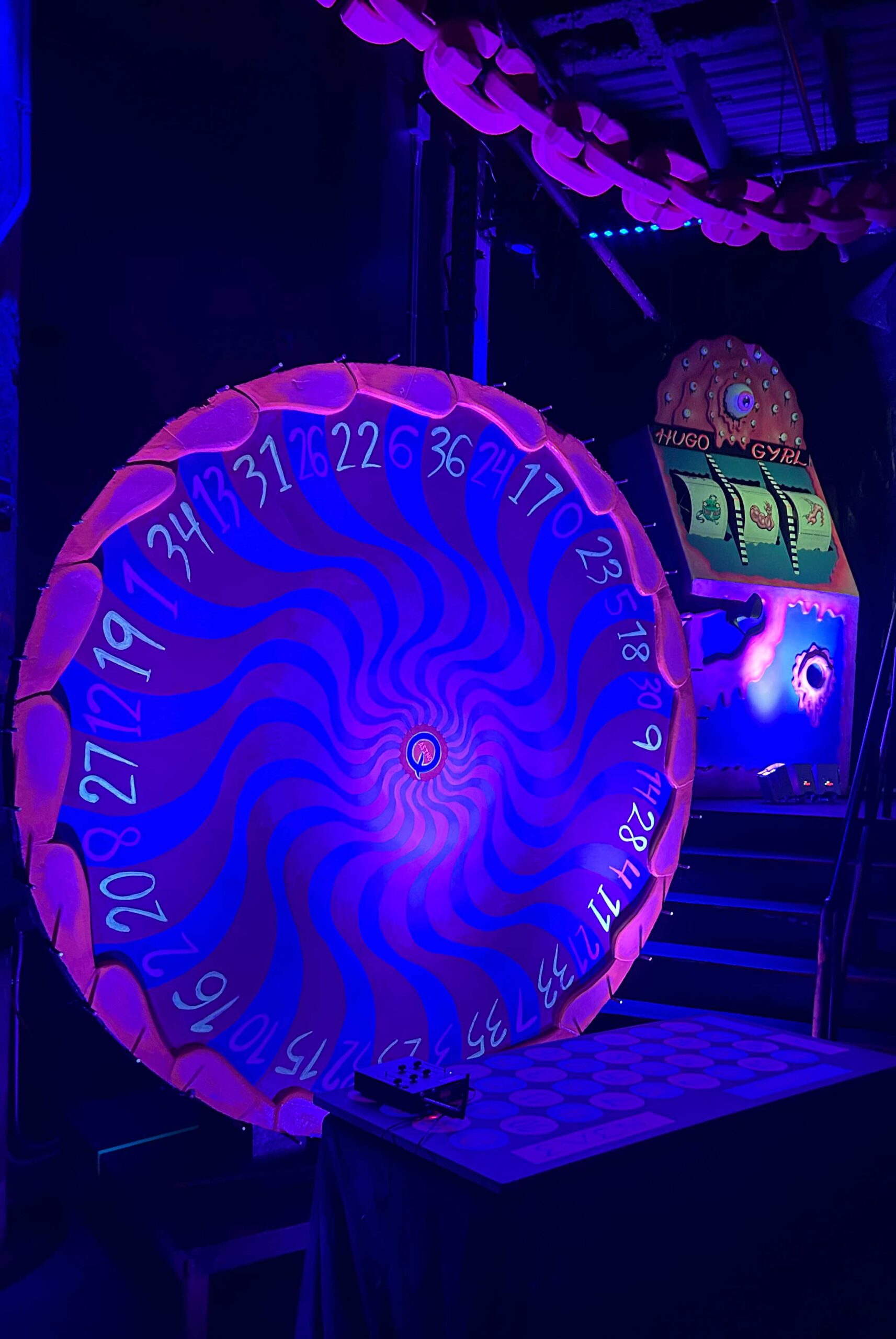

Ellery’s fascination with scale-play—a true size queen who loves things both giant and tiny—peaks in Qasino, his collection of mega-sized casino games. Originally built in 2018 for a New Orleans rave, the collection includes a six-by-eight-foot functioning slot machine operated by pulling a giant mannequin leg, an eight-foot-diameter roulette wheel, a massive Plinko game, and more. The games were almost lost after sitting in a New Orleans warehouse for years. They were being dumped when a friend of Ellery’s driving by serendipitously caught the landlord trying to stuff the giant roulette wheel in a garbage bin and rescued the entire collection.

After touring with Red Bull around the country, Qasino landed in New York, where it’s currently stashed in “some random man’s garage in New Jersey.” But this Saturday, the games will emerge from exile for the queer party Function, where ravers can pull that giant mannequin leg for the chance to twist their fate and win real prizes.

The games are more than jumbo novelties. “In a world where the odds often feel stacked against us, Qasino invites you to spin again. To take chances. To be seen,” he explains. “The games are a different way for people to interact with each other [at parties] that isn’t just about the music or the drinking or the drugs.”

Whether he’s hanging upside down painting political messages on rooftops, designing campaign banners for New York mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani, or body-slamming drag queens in museums, Ellery operates in the tension between beauty and chaos, institution and rebellion.

Making art first, asking permission never—that’s Ellery’s superpower. He echoes the rise of self-taught street artists like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat before him, carving a path from New York’s margins to its cultural center without losing his edge, creating with punk immediacy and letting the world catch up to his vision on its own time.

“You don’t want to play too nice, you don’t want to play too nasty,” Ellery muses. “You want to play just right. You really wanna get under their skin.”