Backstage at the former Barneys New York building, Document spoke with three designers shaping the future of fashion

For the undergraduate Class of 2025 Fashion Design program at Parsons, finals week means one thing: the thesis runway show. On Monday, May 19, over 200 students presented their final looks at A Common Thread, a one-hour showcase held at the former Barneys New York building on Seventh Avenue—a space that once held the early works of Azzedine Alaïa, Comme des Garçons, Proenza Schouler and more, now taken over by the next generation of fashion.

The buildup to a fashion show is always the same. Outside, onlookers pressed against the floor-to-ceiling windows, trying to catch a glimpse of the runway. Just inside and up the marble stairs, designers dashed between racks, fixing hems, taping shoes, and fielding calls from producers as models raced to their places. Upbeat electro pop drumming through the space signaled their entrance from all sides of the room, ready to walk.

At the show, three standout designers caught our attention, each presenting a single look embodying the core of their thesis collection. Will Zornek’s knit yarn spilled into a tattered party dress, Yutung (Tori) Chen’s sharp tailoring took inspiration from a coat hung on a doorknob, and Zewen Shao’s weatherproof design could transform into twelve different iterations—one moment a full jumpsuit, the next, modified into a jacket. Between curtain calls and crowded staircases, Document caught up with the designers to learn more about their work.

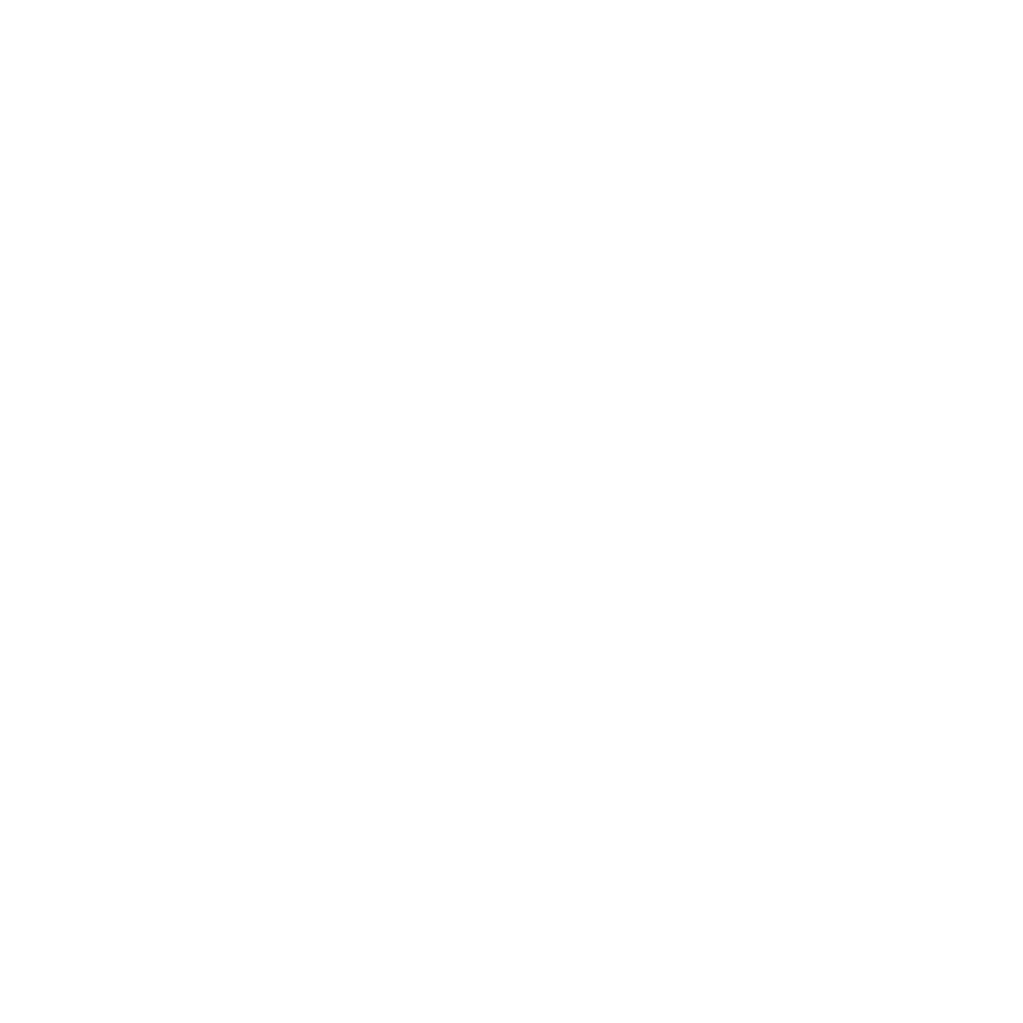

Zornek pulled apart the conventions of knitwear, literally. He distressed jersey yarn by hand, disrupting its usual structure and loosening its threads into soft, irregular weaves. “Making those organic forms was my way of subverting what I would see as a hetero world and making it a queer object, or queer textile,” Zornek explained.

Made of hot pink yarn that seemed to melt, his runway look featured sculpted shoulders reminiscent of a 1920s flapper silhouette. Paired with matching heels, Zornek envisioned the clothing as an object that transformed the wearer. “They’re objects that, when you wear them, they make you feel like a different person,” he said. “They give you the freedom to be something else, like putting on a character.”

Zornek drew inspiration from Madonna, John Waters, and Lady Gaga, anchoring his work in the power of performance and reinvention. “I want it to feel weird, odd, sexy, but also kind of gross.”

Where Zornek leaned into the spectacle, Yutung (Tori) Chen grounded her work in quiet elegance. Her design explored untethered, liminal spaces between wear and use—when a garment is draped over a doorknob or slouched on the edge of a chair. “It’s about capturing those moments that are often overlooked,” she said.

Chen’s look, an elongated trench dress in pale sage, translated that idea into something structured at the top and fluid below. Made from two coats cut into halves, the upper portion of the dress is precisely tailored, while the bottom structure gives way, softening into folds that trail behind the body like a garment slipping from a hanger.

The dress’s soft blurring green was inspired by moonlight. “Moonlight and the shifting of the moon are symbols of the impermanence of time, which connects back to the idea of the in-between time,” she explained. Chen also cited the minimalism of ’90s Yohji Yamamoto and the androgynous cool of model Stella Tennant. She sought to imbue her collection with what she called “the quiet but powerful” energy of that era, with a tomboyish edge. When asked what she hoped the audience would feel, Chen said, “I think [I am] trying to find a quiet space in the chaotic world we are living in now. We can still be powerful without being loud.”

Zewen Shao’s design, on the other hand, came alive in motion. Growing up watching animated heroes like Ben 10 and Kamen Rider, characters who instantly morph into new forms, Shao mimicked that shapeshifting in his garment. His look, made from waterproof technical fabric similar to Gore-Tex, can be worn as a full-length cape, a jumpsuit, a hooded parka, unzipped into pants, or even slung over the shoulder as a bag—in total, it could be worn twelve different ways.

“For most hero characters, their clothes need to be functional for them to move,” Shao said. Agility was at the core of his collection. “I love going outside—climbing, hiking—so every time I do those sports, I need to be wearing functional clothes.”

He has worn the garment himself on multiple occasions, whether in the rain after class or when he needed an on-the-go bag. “You can fold it to store small accessories around your waist,” he said. “If you want to wear it, you can take [the material not being used] out and unzip it. It’s easy to wear and carry so your clothes can adapt to many things.”

Beyond its high-function fabrics, including thermochromic materials that change color with body heat, the garment is playful. Its baggy style recalled Shao’s superhero character’s—turning dressing into an act of transformation itself.

Though these three student designers shared the runway at A Common Thread, their practices could not have been more distinct. Theirs were just three of over 200 collections marking the rise of a new vanguard of designers. Barneys may no longer sell clothes, but its legacy endures as a space for the future of fashion.