Upon her third solo exhibition with Chapter NY, the artist muses on the making and the meaning of her work

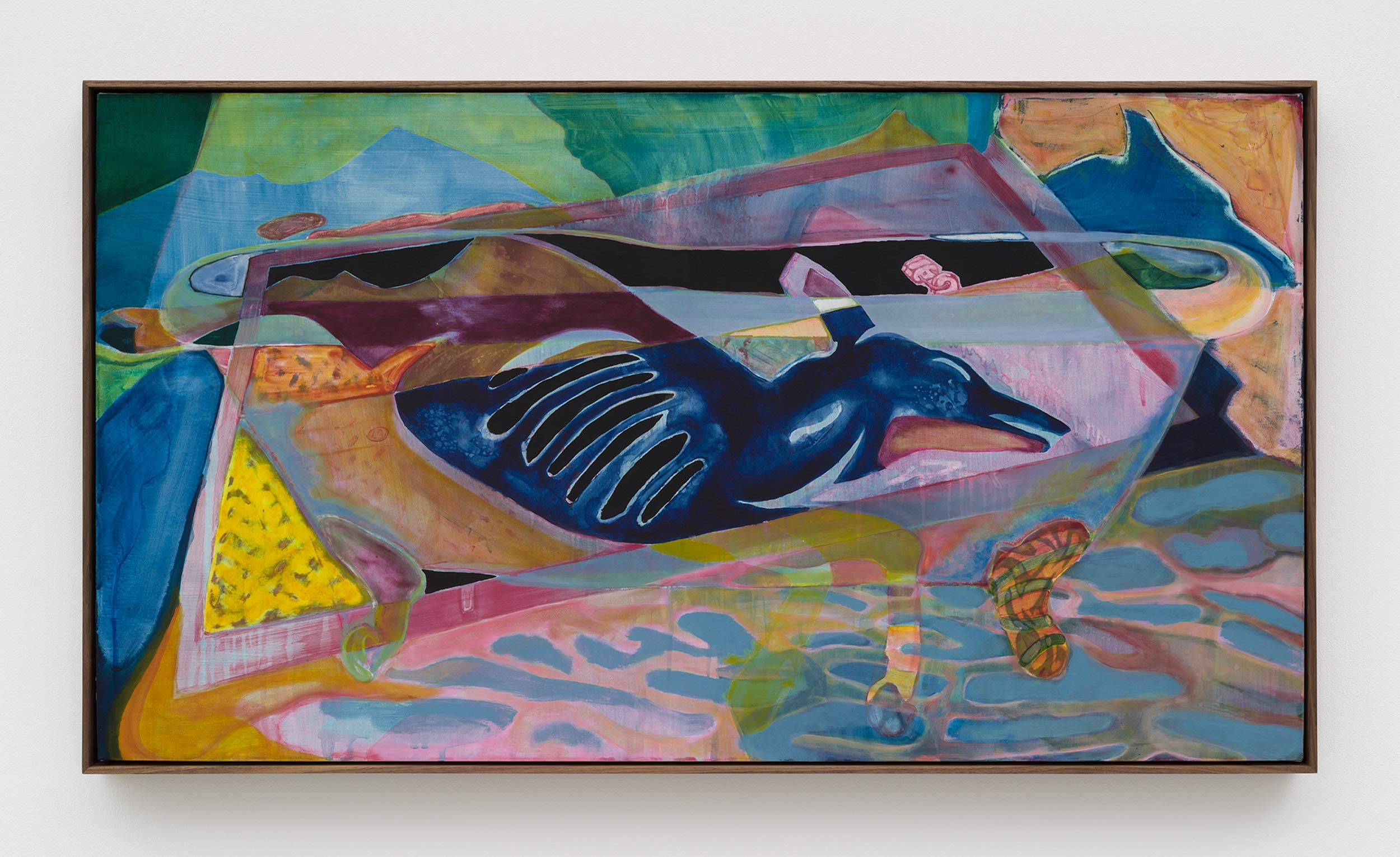

Willa Nasatir may use cameras and brushes, but she doesn’t necessarily make photographs or paintings. “I think medium specificity is a sort of outdated method for categorizing art,” she says. Her process is amorphous, and not easily tied to standard classifications; she first gathers materials, and then abstracts them, applying gouache and acrylics and images atop polycotton and plexiglass.

The way she works speaks to the themes present in the art itself, rendering the everyday surreal, and examining the simultaneity of realities, whereby two stories can exist at once—sometimes in conflict with one another, somehow each maintaining truth. Nasatir is inquisitive about power and the dynamics bred from it. “My work illuminates more than it illustrates,” she explains. Her art exposes; it is dense but not definitive, more preoccupied with prompting questions than it is with presuming absolute answers.

Upon her third solo exhibition with Chapter NY, Nasatir muses on the making and the meaning of her work.

Megan Hullander: How did you go about compiling the work for this exhibition? As it’s your third with Chapter, can you trace any sense of narrative or evolution through them in this space?

Willa Nasatir: One piece at a time! But when I zoom out, I have made shows that are all paintings and shows that are all photographs, and each time I’ve hoped to incite a conversation where the work is actually being considered in relation to its opposite form. My photographs are often misidentified as paintings, and I like that inaccuracy. So it feels natural to show them alongside one another, existing in a continuum.

Megan: ‘Multimedia’ is a term that is often adopted by contemporary artists, but rarely employed to the extent that you exercise it. How do the multiple mediums you work within connect to the thematics of your work?

Willa: Whenever I say ‘I’m a painter,’ or ‘I’m a photographer,’ it feels disingenuous. Some people really like that kind of categorization, but I don’t want to be one thing. It relaxes me to work in disparate mediums that both deflate and expand one another. In tandem, my work can undermine ideas of what a ‘painting’ or a ‘photograph’ is supposed to be. I think medium specificity is a sort of outdated method for categorizing art.

“An artist’s belief system is embedded in their work, even if the work, on its face, doesn’t depict those beliefs.”

Megan: Your work is often described as fragmented, surreal, and otherwise complicated. Do you think art needs to be provocative or challenging to have meaning? How do you balance aesthetic pleasure with conceptual dexterity?

Willa: I like to try to ditch myself in the process of making something. It’s exciting to me when the subject matter of the painting or photograph I’m making becomes unrecognizable. I don’t know exactly how to talk about my paintings, and that is exciting to me—it means I am actually inside a process that is alive, rather than standing at a remove from it.

I feel that an artist’s belief system is embedded in their work, even if the work, on its face, doesn’t depict those beliefs. My work illuminates more than it illustrates. Broadly speaking, I think pleasure can be a useful tool for turning the world into something more livable. Something beautiful can also be offensive or uncomfortable, depending on who is looking at it. But I want to have a good time making the things I make, because I spend so much time doing it.

Megan: What is the process of making the ‘everyday’ surreal like? Is it something that comes into your daily life somewhat naturally, or is it a more active process?

Willa: I’m interested in the techniques people use to [adjust] the volume of their consciousness. Ayahuasca or silent meditation retreats or sensory deprivation tanks, for instance—most of which I haven’t actually tried. The desire to feel more or less in any given moment is so distinctly human. Allowing yourself to view the everyday as somehow charged rather than banal is in line with that instinct—the hope being to both tether yourself to the life you’re in, and to free yourself from it.