‘Brutes’ and ‘All-Night Pharmacy’ destroy the canonical bad girl, allowing for pure(r) heroines to emerge

On either side of the country, roughly 30 degrees north of the equator, a young woman is missing. In Los Angeles, California, the missing girl is Debbie: an erratic older sister who vanishes from a hospital bed the night after being stabbed. In Falls Landing, Florida, it’s Sammy: an outcast Jesus freak turned mistress. But these are not main characters—not even in the stories of their disappearances. These girls were lost even before they went missing.

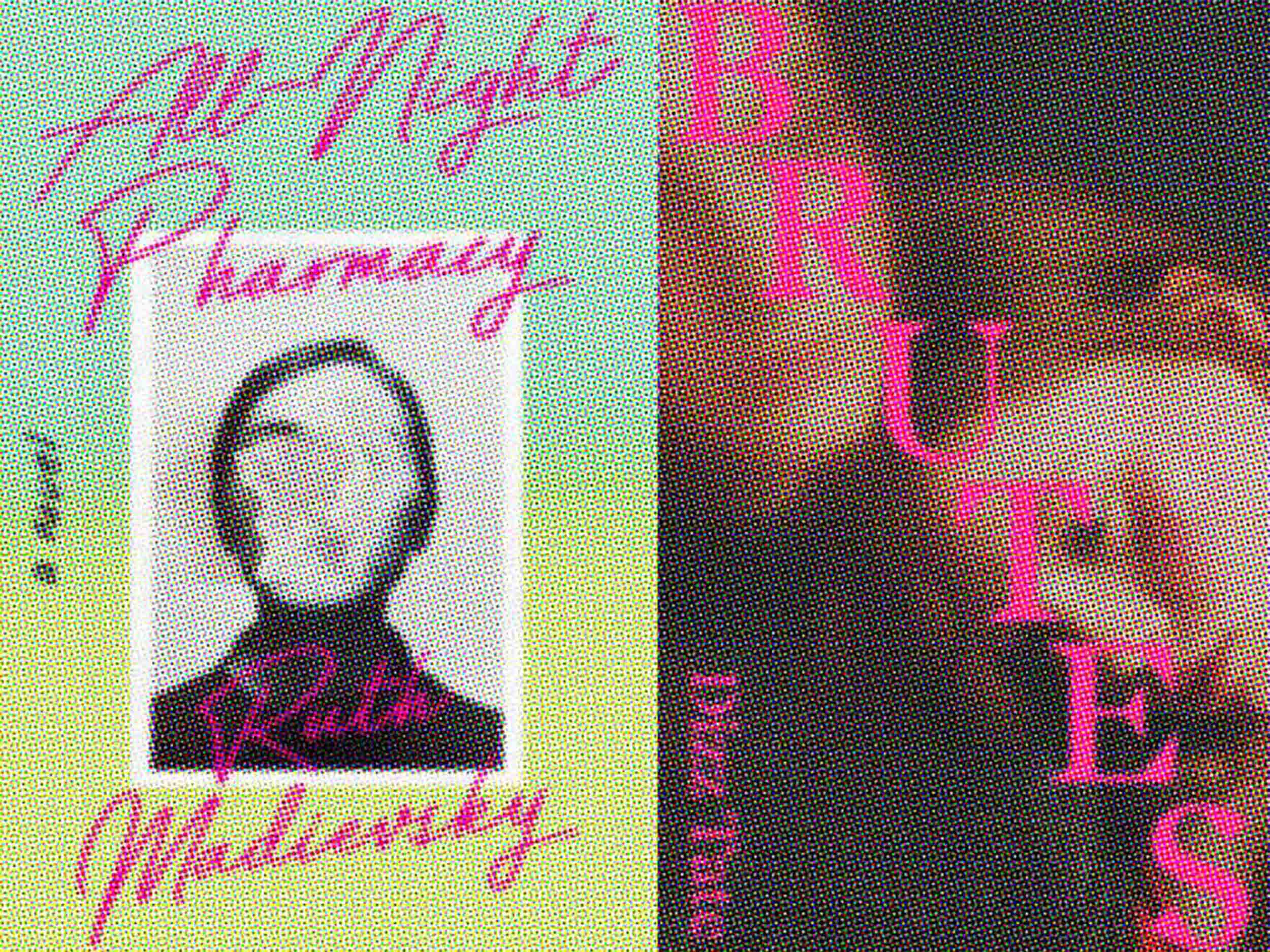

The twin mysteries of Debbie and Sammy are the premise for Ruth Madievsky’s All-Night Pharmacy and Dizz Tate’s Brutes, respectively. The two buzzy debuts, published this year by Catapult Books, are sort of incidental sisters—both are invariably described by reviewers as “Lynchian,” “atmospheric,” and “dark”—following young women in the wake of an important older girl’s disappearance. Where All-Night Pharmacy is a Soviet intergenerational trauma neo-noir with a dive bar basecamp, Brutes is a Florida gothic with teetering ladders and lake monsters and bougainvilleas bursting with bugs. Neither book looks much for their missing girls. Madievsky’s unnamed narrator avoids searching for her sister for years, and when Debbie (spoiler alert!) is found, it’s an anticlimactic reunion the lost girl had herself orchestrated. The Greek chorus narrating Tate’s novel in a collective first-person plural declare they “know where Sammy is, of course;” they had helped hide her in the first place. In either case, the mystery is not the lost girl’s location: Her sudden absence ignites the narrative, sure—the first line of Brutes asks, “Where is she?”, a refrain iterated throughout the novel—but finding her is beside the point.

I bring this up because of real bodies, the ones that have been found, and, now, the bodies for which an arrest has been made. These are the bodies of the Gilgo Four, a series of sex workers whose corpses were found in 2010. Their disappearances weren’t considered worthy of serious, sustained investigation by authorities; at a press conference, a newsperson was overheard remarking, “I can’t believe they’re doing all this for a whore.” Arguably, the publication of Robert Kolker’s Lost Girls (2013) and the subsequent titular Netflix feature film (2020) helped to rouse sufficient discourse to prompt a task force. Soon after this renewed investigative effort, the subtitle of Kolker’s bestseller—An Unsolved American Mystery—was outdated: The suspected killer was arrested last month.

“Rather than serving as a site for male contemplation, for Madievsky and Tate’s protagonists, the lost girl is an exterior foil against whom the narrator can discover herself.”

The lost girl is a parable of vice, a fable from the puritanically-tinged folklore of youth. (Think: the hedonistic teenagers swapping spit, groping in the front seat of the car, while a hook hand grips the door.) The lost girl is mute and lives mostly off the page; under no circumstance should her consciousness enter the text. She is a subject of mystery, even in narratives that seek to elucidate the opaque experience of girlhood; Brutes advertises itself as an alternate imagining of The Virgin Suicides, assuming that to inverse the (dominant) gender of its narrating Greek chorus is to subvert its voyeurism. In Madievsky and Tate’s books, it is clear we don’t want to find the missing girls. They have already relinquished their respectability, and with it, their authority.

This is not to suggest that the narrators are puritanical virgins themselves: All-Night Pharmacy’s is a drug addict, a thief, a cheater; Brutes’s narrators are, well, brutish. Where Madievsky’s protagonist is volatile and sometimes cruel, Debbie is a supernatural predator: her “extra canine tooth” is proof she “might have been a hunting dog or a vampire” in another life; she is likened to “those possessed toys that lit up even after you took their batteries out.” Where the gang of girls narrating Brutes push and taunt and mock, Sammy is an outsider altogether, her shaved head proof of her bald sexuality: “We hid our faces because we were certain that someday someone else would reveal them back to us, tuck our hair behind our ears, and tell us how beautiful we were, had been all along, in secret. None of us could believe Sammy had hacked off her curtain, revealed herself by choice.” Watching Sammy cheat—she sneaks out to kiss her best friend’s boyfriend—the chorus rebukes her: “We were moral girls and we did not believe in infidelity.” Her affair upsets the small shrine they made for her in their collective mind. Two weeks later, Sammy is missing.

In Dead Girls, Alice Bolin writes of the latent heterosexual fixation in lost girl narratives: “The victim’s body is a neutral arena on which to work out male problems.” But the problem with Debbie and Sammy is that they are both alive, and the storytellers are themselves girls. Neither dead nor pure, the missing young women are not “virgin martyr[s]” worthy of “the investigator’s haunted, semi-sexual obsession”—not victims at all. An alive girl, even a lost one, has a mouth, and with it, the possibility she might narrate her own story, reappearing and eradicating the mystery with her presence. She is, then, shunned off the page: Rather than serving as a site for male contemplation, for Madievsky and Tate’s protagonists, the lost girl is an exterior foil against whom the narrator can discover herself.

As much as the lost girl is maligned—and as much as she is missing—she is a fertile narrative tool. The night before Debbie disappears—before the narrator stabs her in a drunken daze—her influence is lamented: “I hated Debbie, for showing me yet again who we were.” For the protagonist, Debbie is a lantern hung low, throwing unflattering shadows on our narrator’s face from her inferior moral position. For the girls of Brutes, Sammy is an introduction to the grown-up world; the novel’s narrative jumps to the future, showing that their adult lives continue to orbit around her disappearance and its ensuing events.

“When we imagine missing girls to possess interiority, their absence is made more urgent and less abstract.”

The promiscuous, corrupt, and ultimately unsalvageable girl is an archetype of millennial female fiction—not as the heroine, but as the springboard from which a complicated but loveable protagonist can emerge. I think of Suzanne in The Girls, who seems to jumpstart bored, homely Evie Boyd’s life; she reflects as an adult: “No one had ever looked at me before Suzanne, not really, so she became my definition.” These girls—and they are always called girls, even when they behave so much like women—are invariably brazen and beautiful and the subject of a borderline sexual obsession. Their destruction is fated, not at the hands of a clean, lovely heroine, but of her own volition. It’s a form of narrative femicide: the lost girl’s absence makes space for the narrator’s life. It is, as Bolin notes, the concept Julie Kristeva wrote of: “a kind of original, generative anger, expressing a need to destroy the mother, the origin place, to become an individual self.”

That the success of Kolker’s journalism that seemingly pressured the investigation that would discover the Gilgo Four killer is, perhaps, a parable: When we imagine missing girls to possess interiority, their absence is made more urgent and less abstract. The missing girls of All-Night Pharmacy and Brutes share a status—though, notably, not a fate—with the subjects of Kolker’s “true crime masterpiece.” His nonfiction narrative endows each dead woman with a voice, ambition, and history—such exercises in fabulation that the missing girls of Madievsky and Tate are granted in sparing disinterest.

These two novels admirably and ambitiously seek to complicate the thriller narrative with memorable, richly-realized narrators. The comparison to a real-time true crime story exhausts itself quickly. What I mean to ask is: Can we imagine the lost slut as a coming-of-age heroine, neither infantilized for her naivety nor maligned for her sexuality? Erin Kate Ryan writes, “Symbol of what happens to girls who go bad… [The missing girl] is forever trapped in prelude; she will never [be] the hero of her own story.” But I want her in the first person. I want to stop the red leak of Debbie’s wound, to feel the flicker of the creature blooming in Sammy’s belly. I want to go missing with the lost girl. I want to know what she finds out beyond.