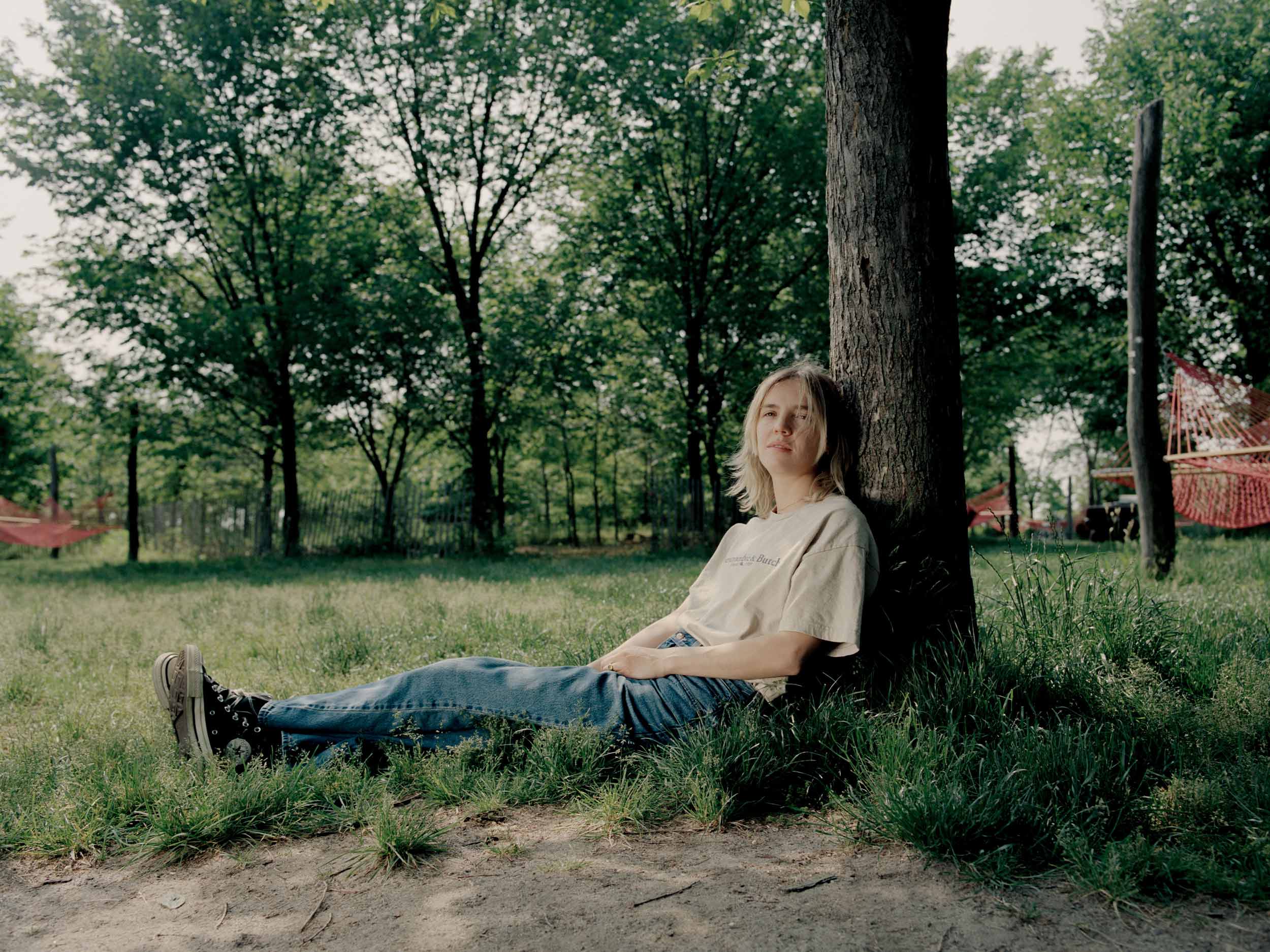

On new album ‘In The End It Always Does,’ Amber Bain charts the trajectory of a queer love story, from beginning to bittersweet end

Amber Bain still remembers the last line of a poem her ex sent her: “I’ll feel it all for the rest of my life, no matter what happens.” She was sitting on a fire escape in LA, and burst into tears after reading it. “It was such an amazing, detailed, and accurate perception of something that was beautiful in both its ugliness and its sweetness,” she recalls. “I was really choked up by it. And then my friend and co-writer Katie [Gavin] looked at me and was like, You know what the saddest thing is? She won’t.”

At the time, Bain laughed it off and called her friend an asshole—but several months and one breakup album later, she’s come to see the truth of the assessment. “When you’re heartbroken, it feels like it will never end—but you should hold on to those feelings, because they won’t last forever. And the idea that you one day won’t care about the thing that’s causing you pain is, in a way, even sadder than the idea that you always will,” she says. “That’s what I’m speaking to with the title In The End It Always Does.”

Released under her moniker The Japanese House, Bain’s sophomore album sees her delve deeper into themes of queer intimacy, trauma, and self-discovery—exploring familiar topics with a heightened candor, “teetering on the edge of an overshare.” Inspired by the experience of entering into a throuple with two women who had been dating for years, the record sees Bain chart the trajectory of the affair from its sizzling beginnings to fizzling end—capturing the particular and sometimes banal details of falling in love, and the bittersweet nature of a relationship’s unraveling. “Loving two people can be incredible, but it’s also very intense emotionally,” Bain reflects, joining me on Zoom with her dachshund, Joni—named after Joni Mitchell—resting on her lap. “It’s hard enough to love one person—because as soon as you’re invested in something, it has the potential to hurt.”

Though Bain doesn’t shy away from addressing the dynamic underpinning this chapter of her life, the emotional experience she describes could just as well map onto more conventional relationship structures—which Bain reports she has since returned to, in the form of a committed monogamous partnership with her current girlfriend. However, she doesn’t regret the experimentation that brought her here: “It can be really interesting and valuable to explore new avenues of romantic relationships. I feel that queer people are really open to that—because, just by being queer, you are already breaking the norm. It’s like, Okay, if that feels so good, then what if all the other stuff we’ve been told is normal is bullshit?” she reflects. Such realizations serve as the undercurrent pushing Bain’s work along, and fueling the self-confidence with which she explores her own vulnerabilities in her new album. “I’ve embraced what I’m good at—which is to be on the edge of embarrassment,” she says. “There’s a fine line between what’s cringe and what’s heartwarming, and I’m learning to tread it—whereas before, I never would have gone anywhere near that line.”

In The End It Always Does sees Bain lean further into pop sensibilities, with tracks like “Touching Yourself,” an unabashedly catchy earworm about desire and heartbreak that mines the friction between the song’s upbeat sound and melancholy lyrics. Equally unexpected is Bain’s collaboration with other musicians on the album, including the likes of Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon, MUNA’s Katie Gavin, Charli XCX, Matty Healy, and George Daniel. It’s a choice inspired by Bain’s increasing confidence in her own musical abilities and reputation, which she says has made her “less defensive” of involving other people in her creative process.

Bain’s desire to prove herself is understandable. At one point, The Japanese House was rumored to be a side-project of 1975 frontman Matty Healy—an industry conspiracy theory that took hold when she released her 2015 EP Pools to Bathe In through Dirty Hit. Between Bain’s association with the label, her project’s mysteriously anonymous name, and a lack of public appearances, she was soon fielding more questions about Healy than her own work. She eventually chose to step into the spotlight in order to dispel the rumors, lest the mystery of her identity become bigger than her music itself.

The fact that Bain’s use of a moniker would lead her to be mistaken for a man is ironic, given its origin: The Japanese House is a reference to the summer home Bain stayed in as a child, where she spent a week posing as a boy, and subsequently experienced her first queer romance with the girl next door. “She fell in love with me because she thought I was a boy, and I had to tell her at the end that I wasn’t. It was this horrible childhood heartbreak: She was running after the car when I left, just totally distraught,” Bain says. “I’ll never forget it.”

The encounter also inspired “Boyhood,” a rhapsodic track that sees Bain address the intersection of trauma and identity: how the adversities we face become inextricably linked to who we are. It’s a response to Bain’s own ruminations on the boyhood she never got to experience—and to how, despite feeling stifled by the constraints of femininity, she wouldn’t trade it for an uncomplicated adolescence. “That song is about recognizing the parts of yourself that maybe aren’t the most healthy—like the way you deal with conflict, or solve mental health issues with alcohol, which are things that I’ve struggled with in the past—but also realizing that, if I got to press a button and have a boyhood, I wouldn’t be who I am,” she says. “I think a lot of queer celebration is about embracing all the things that contribute to who you are—and being like, Thank you for making me gay, I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

In recent years, Bain has also grown more open about her sexuality—utilizing female pronouns in every song, which she describes as an “unconscious” choice, in a way that it wouldn’t have been years ago. “My music is under that umbrella of, like, ‘gay’ music—which is a genre within a genre,” she says. “I think it inevitably sounds queer, because it is. And I’m happy that my fans are openly queer, too. I always think about the time I found out my favorite musician was a lesbian, and I was just so relieved! It immediately helped me take a huge step towards accepting myself.”

For Bain, the boundary between life and art is a porous one: Often, she turns to songwriting to interpret aspects of her relationships as they unfold, accessing her subconscious desires before she’s even ready to accept them herself. “Songwriting doesn’t feel like it’s in my control at all. It feels like an innate thing that’s channeled through this weird little human vessel,” she says. “I’ll write a song and not know why, and then I’ll read the lyrics afterwards and be like, Oh, is this what I want? Is this what I think?”

Bain’s embrace of autobiography is evident, too, in her approach to music videos, one of which features her exchanging intimacies with a recent ex, Marika Hackman: the subject of the song. “Some people are like, Why do you do this to yourself? But I really enjoy the result of wading through the pain of being friends with someone you’ve dated,” she says. “It’s so hard to experience heartbreak, but at the same time, it’s amazing to love something so much that you are broken by losing it—and I feel lucky that I get to immortalize these moments in my life through music. I think that’s a desire that drives all art: the urge to turn a feeling into something physical.”

Photography Assistant Gabrielle Gowans.