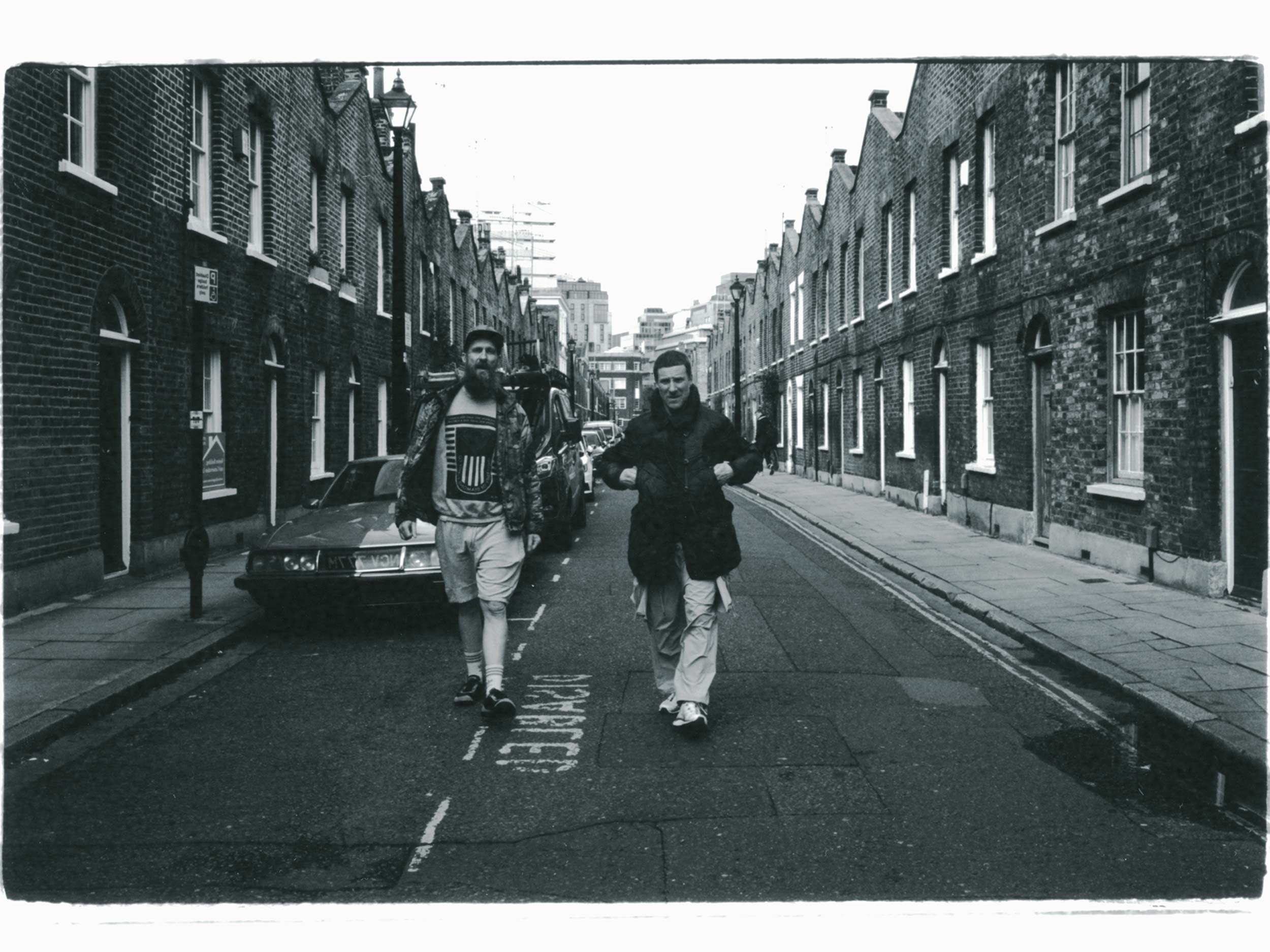

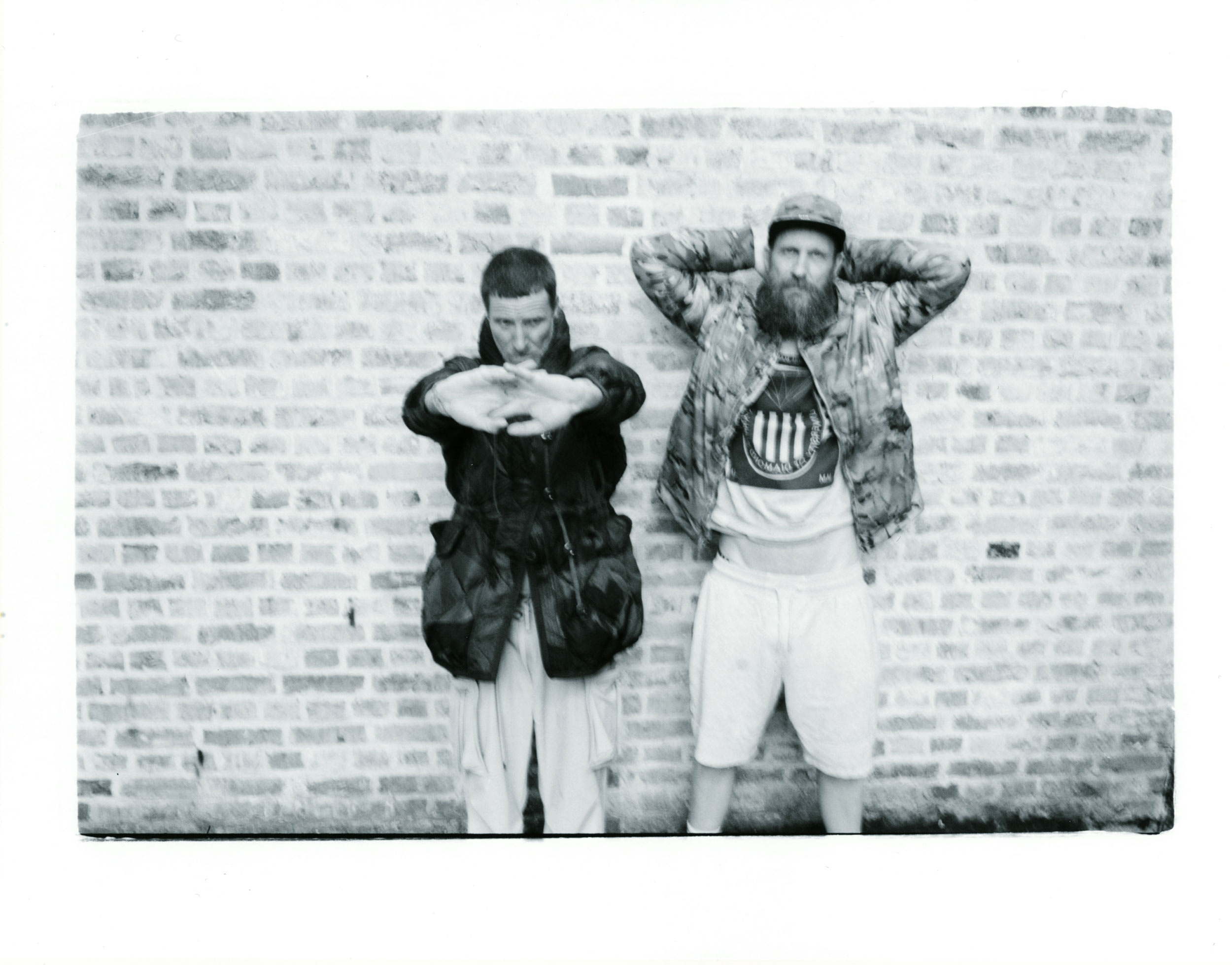

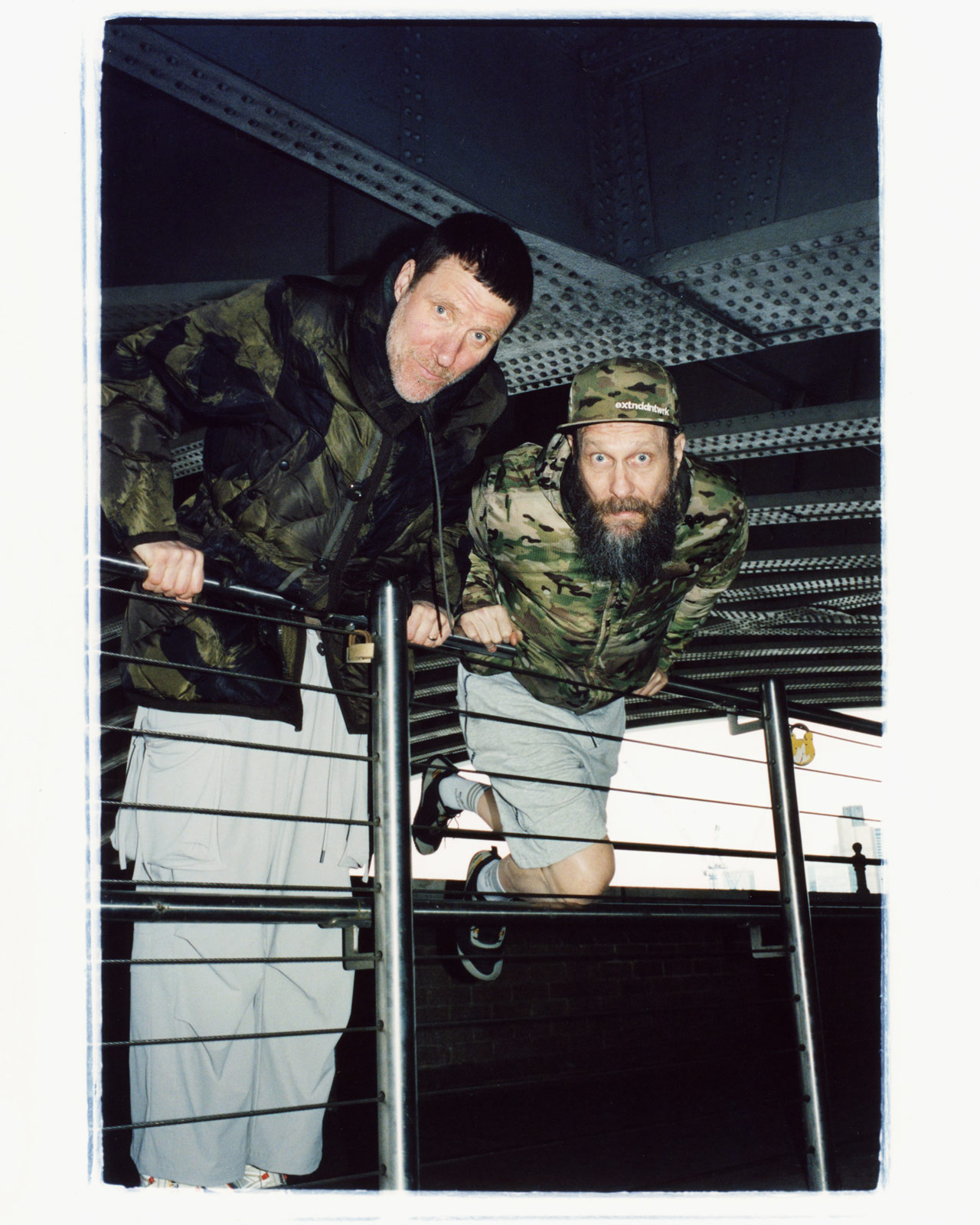

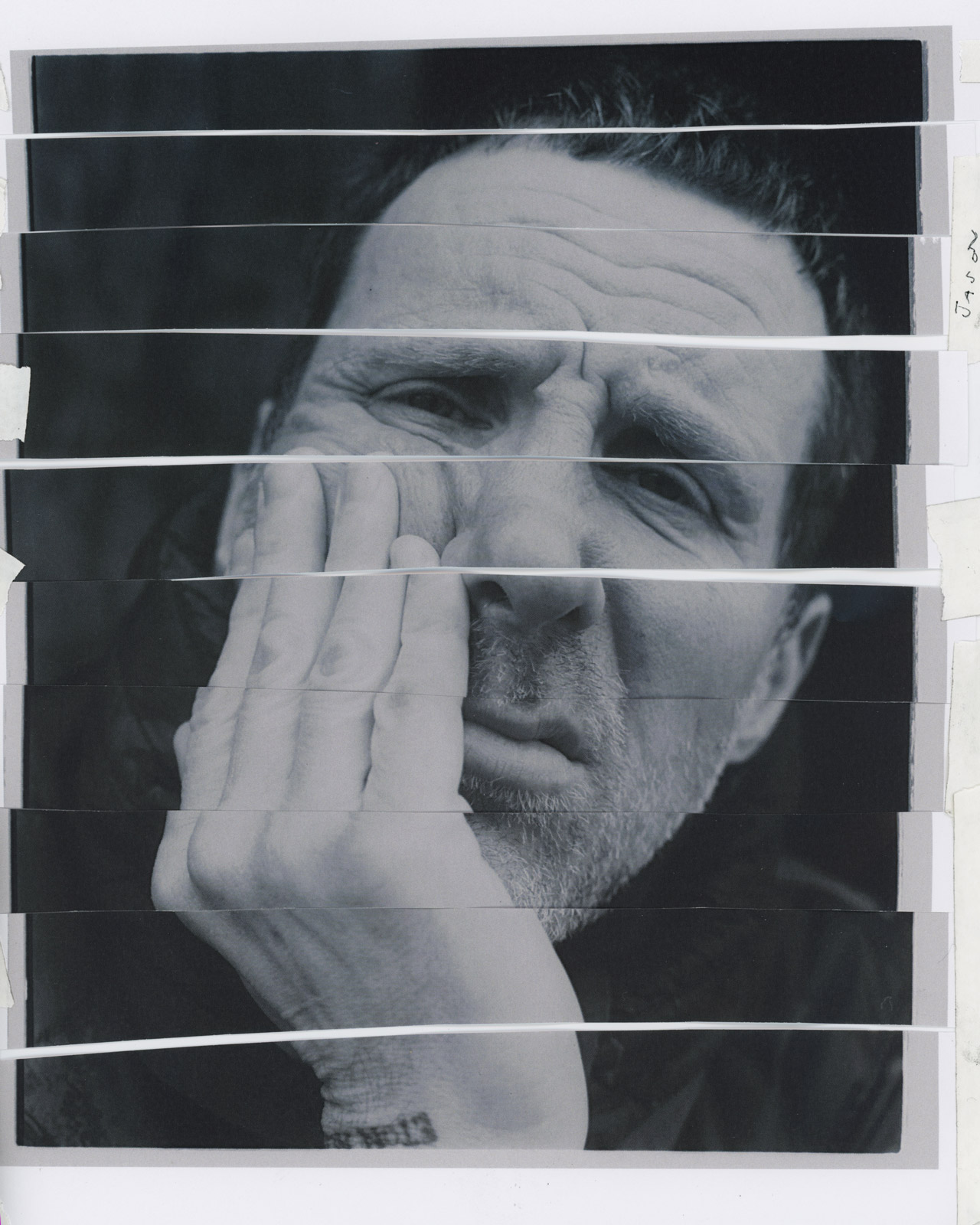

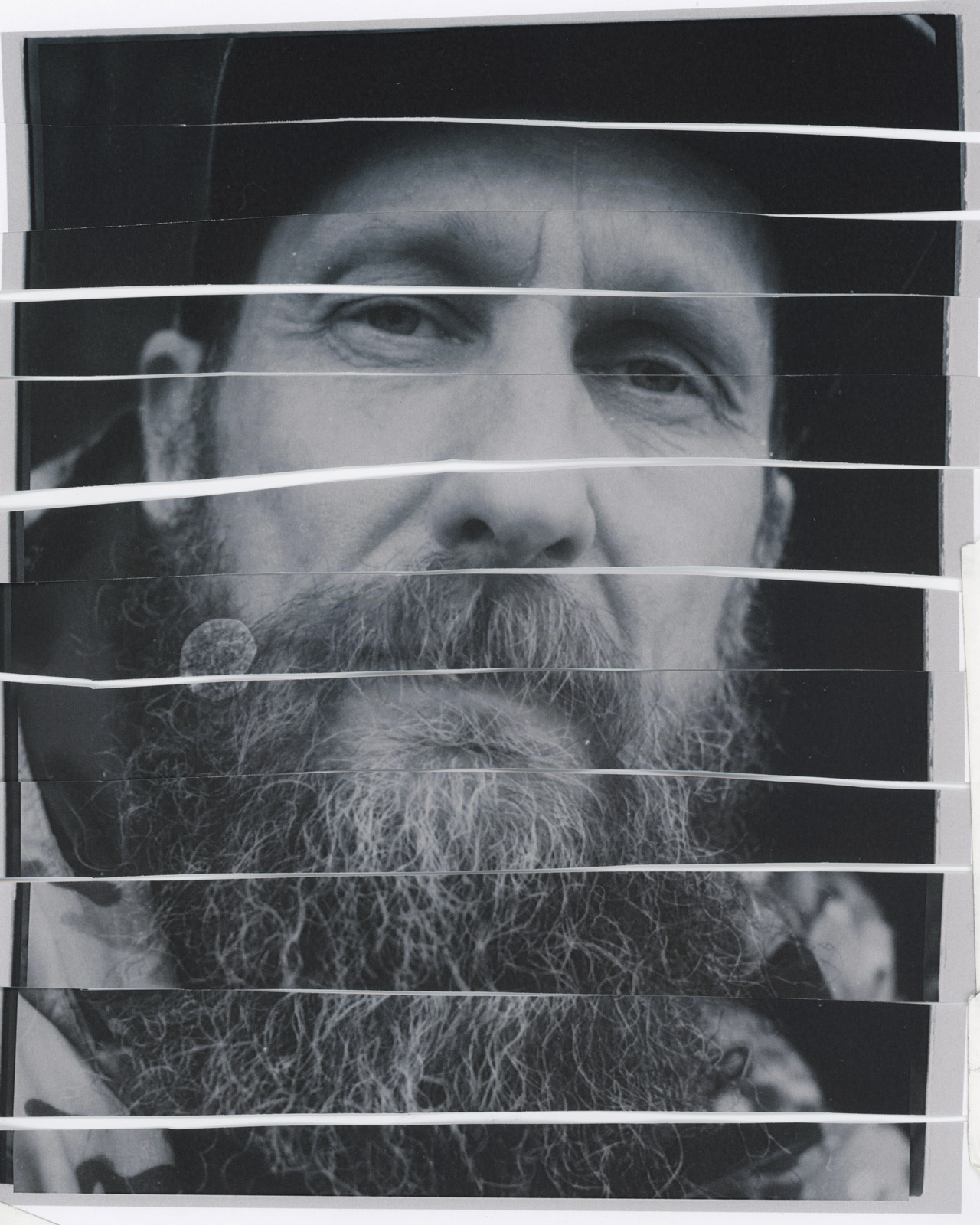

Following the release of ‘UK GRIM,’ Jason Williamson and Andrew Fearn join Document to disclose why they’ll keep going until they “drop dead”

Sleaford Mods, by its own analysis, is characteristically akin to a comedy routine. “They’ll attack themselves, and then they can have a go at everybody else,” says the musical half of the duo, Andrew Fearn, drawing parallels between stand-up and the self-hypocrisy of lyricist Jason Williamson. To be sure, their latest record UK GRIM doesn’t limit itself to its own posturing—which, Williamson explains, is mostly a result of the smoke blown up his ass following the success of their previous records. In keeping with the duo’s reputation for unencumbered critiques of the politically ruthless and culturally reckless, UK GRIM is scathing in the jabs thrown at its many targets.

The project was born from austerity-era Britain—and consequently, the pair’s home country and the people running it are long-standing muses. (“I got crisis stamina, full marathon, four poo breaks / I can feel the shit from your crisis rays / Spray up my back, because in England nobody can hear you scream / You’re just fucked lads.”) So, too, are the people they know more intimately, or at least adjacently. (“You’re not DIY, you’re a fucking twat / You look like Fred Dibnah and your haircut’s crap / You’re in a shouty band, you’re not original, man.”) Who exactly the subjects of such songs might be, Williamson won’t say—though if you care to hazard a guess, and have an adequate sense of the current musical landscape and its “white bloke aggro bands,” you’ll likely be exactly right.

Following the release of UK GRIM, Williamson and Fearn join Document to reflect upon their anger and anxiety, and to unpack how a career’s coming of age impacts its adequacy.

Megan Hullander: This record feels very angry, more so than your earlier work. I feel like there’s a tendency to associate that sort of anger with adolescence—but have you found yourself growing angrier with time?

Jason Williamson: We can get pretty angry, can’t we? I think it’s more that, these days, when you get angry, it’s more refined. There is some kind of self-control with it. I’m starting to learn that a lot of the things I was angry about when I was younger had to do with my own experiences, and not necessarily things that I was directing my anger at. So I tend to view anger, these days, in the sense of why I am feeling it.

Megan: Something in your work that feels different from a lot of music—especially contemporary music—that treads into critique, is the specificity with which you do it. Do you think that specificity is necessary for commentary on people and politics?

Jason: Yeah, I think it is. This is our world—the humor and the names and whatever we’re talking about. I think I got that from rap records, where you can’t know what they’re going on about full-stop; you’re not going to know what a 22-year-old Black man from Compton is going on about, but you can feel that energy, relate to it. I thought it wouldn’t be a problem to talk about things that people weren’t necessarily aware of, as long as the songs were good in a way that was natural.

Megan: The production on UK GRIM feels almost rawer and more stripped-back than it did on Spare Ribs. Was that something you went into this record wanting to do?

Andrew Fearn: I mean, a lot of it’s quite minimal. For me, it just feels like we made another album. We tried a few different styles, maybe. Like, initially, I thought it’d be cool if we tried something that sounded a bit more drum and bass. And then, I forget about that idea and just write a bit of music.

Jason: This is the beauty of it. I think this is why it continues to have such a strong life force, because there’s not an anxiety that clings to it. It’s all made in a calm, almost forgetful, dismissive way. I’ve made that, I’m happy with it, I’ll move on. You don’t think anything else of it.

Megan: The hypocrisy that thematically dominates a lot of the record seems disconnected from that ease you describe. Especially as some of that hypocrisy is directed at yourself, which can’t be a natural process to get to.

Jason: Oh god, yeah. Without a doubt. Lyrically, there is an emphasis on the fact that—although there are a lot of targets—there’s an ongoing awareness of myself. I’m not perfect, either. And there’s no right or wrong—it’s just me sounding off. But I quite like that. I’ve kind of eased into the fact that I’m just an idiot. I’m not the Mr. Know It All that, perhaps, I thought I was a few years ago, when the band took off—getting smoke blown up my ass every two minutes by people saying, Oh, lyrically, the songs blah, blah, blah. You do get a little bit of an idea about yourself, a self-image that isn’t necessarily true. It’s about coming to terms with the fact that I’m just like anyone else.

Andrew: A lot of comedians do that. They’ll attack themselves, and then they can have a go at everybody else.

Jason: It makes it easier. It adds a bit more reality to it.

Megan: You’re almost talking to yourself on some of the songs. Maybe it’s not all that deep, but I wondered if that was like a sentient narrator, another character—or if it’s more you, looking back at a previous self.

Jason: ‘DIwhy’ is criticizing a lot of other people, but at the same time, it’s having a conversation with other people. A lot of the conversations should be two-way, but they’re not—because there’s nobody else there to record the thing with me. So I’m just playing two parts. I quite liked the idea of the transparency of trying to mimic other voices, or trying to be someone else.

Megan: Tracks like ‘DIwhy’ felt very pointed. And that’s maybe one where you’re not explicitly calling out names, but it feels that it’s less of a broader commentary on culture at large, so much as towards a specific person.

Jason: There’s a handful of actual people that I’m referencing there. It’s probably three or four that are definite characters, definite people that exist, that are walking the face of the earth as we speak. Then, other times, stuff like ‘Tory Kong,’ is just an absurdist collection of words. But I am, again, sort of attacking various people. It’s under the guise of absurdism. It’s not really making any sense. One or two words might relate to somebody, do you know what I mean? But ‘DIwhy’ is a little bit more transparent.

Megan: Do you think those people would be able to identify themselves? Or, because it’s a conglomerate, it’ll be like, ‘That can’t be me, because my hair isn’t like that.’

Jason: I might rejig some of the details. So somebody might listen to it and think, Well, that’s not me—but it actually is.

Andrew: You’re not too descriptive. You don’t say anything like ‘man bun,’ or anything like that.

Jason: I think it’d be humor if I did, wouldn’t it? I did that in the past. And the obviousness of who you are having a go at doesn’t live to haunt you, but sometimes you do feel a little bit exposed. I’d rather just keep it—

Andrew: You don’t know though. Some people out there might actually find it funny. And they are a bit of a twat.

Jason: Well, that’s the idea. It’s our job to re-educate some of these people—without trying to sound like some fascist.

“Sometimes, I get a little bit intimidated by other bands, because they’re so terrible, and yet they’re more successful.”

Megan: How has the landscape of contemporary music —whether that be music you like, or music you don’t—influenced the way you think about your own music?

Andrew: I like it, but it doesn’t bother me. It’s not what I want to do. You’re supposed to enjoy music, aren’t you?

Jason: Andrew is really good with that. He doesn’t let things interfere with his own energies. Sometimes, I get a little bit intimidated by other bands, because they’re so terrible, and yet they’re more successful—it doesn’t intimidate me as much as it bothers me. That does go into the lyrics, it definitely steers the course. And also the energy of wanting to survive. Although it isn’t a competition, it is a bit dog-eat-dog, the music industry. And I’m always conscious that we haven’t necessarily got to stay one step ahead, because that’s just stupid. But it has to be vibrant. And we’ve got to be alive in this.

Andrew: There are really only two ways you can go about it: You can do something that already exists, or you can carve your own sort of style, like we have. Some people probably think we’re shit because of that, because they like contemporary music.

Jason: [Laughs] So many people buy into music, but it’s almost like fixing the tap or putting the kettle on—it’s just another domestic commodity. I don’t want to generalize, but my experience of people that just dip in and out, or have a relaxed attitude towards music—they don’t think about it in a creative or progressive sense. They’re quite submissive in their tastes.

Andrew: Music academia, as well—there are so many people that have such ability on the piano, on the guitar, which is great. I’m not knocking that at all. But they’re not being progressive with music. They just play an instrument.

Jason: Yeah, I think it’s completely different. What’s the point in mastering the crashing barre chord, like Pete Townshend used to do, or mastering blues guitar when it’s already been done? You’re just replicating someone else’s ability. To me, there’s no difference between doing that and making a table.

Andrew: We all need tables, I suppose. It’d be sad if those skills were lost, but I don’t think they really contribute to the progressive nature of music anymore. It kind of holds things back, and you just get more copycat bands. The general public needs a bit of educating. They’re impressed if someone can play competently, but it doesn’t mean it’s enjoyable to listen to.

Megan: Have you found that your work resonates with your fans in the way you intended it to, or hoped it would?

Jason: I never really think about what they’re going to think. Sometimes, people get the wrong end of the stick, or just don’t understand it, or just don’t like it—and that’s fine. But you don’t have to come online and fucking tell me.

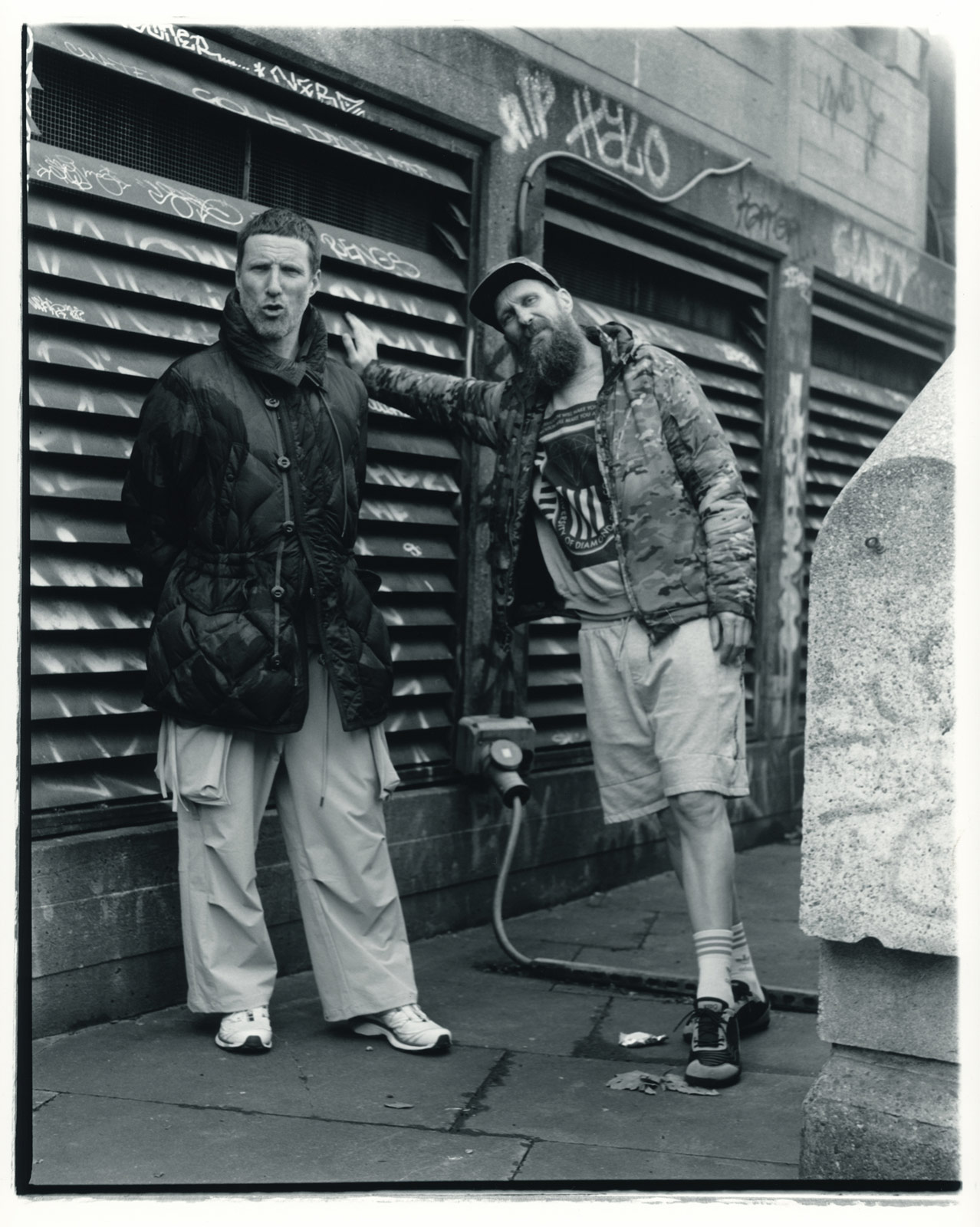

Andrew: Some people think you’re famous. There was that one time in Liverpool, walking back to the venue before the gig, and some bloke was like, ‘What are you doing, walking down the street?’ Expecting me to be in a limo or something.

Jason: Walking down the street? You? Some people are so daft. I mean, you gotta love the public as much as you hate them sometimes. Because a lot of them can be really nasty. I mean, I can. I guess we can all be nasty, can’t we? Some bloke accused me yesterday of being a multimillionaire. He said, ‘Oh, you got 1.6 million quid in the bank.’ I said, ‘Who told you that?’ 1.6 million quid? I haven’t got that. I’ve not clicked on it, but I’ve seen online, it says, How much is Andrew Fearn worth? and How much is Jason Williamson worth? I don’t know where they’re getting these figures from. But I don’t have 1.6 million quid.

“Sometimes, people get the wrong end of the stick, or just don’t understand it, or just don’t like it—and that’s fine. But you don’t have to come online and fucking tell me.”

Megan: Given the reputation you’ve established, do you ever feel like there’s an unwanted pressure to write about certain things, or to give your opinion on things that maybe you don’t want to?

Jason: You can’t help but put it in, because it’s so transparent—the corruption so in-your-face that you can’t not mention it. That the people in government are, for lack of a better word, absolutely fucking useless. The idea is to govern the country and lead the country, and to look after the people underneath it, which isn’t happening. It’s been like that for the last 12 years. We’re older these days, and we’re not going to feel like we have to write something that’s just not going to work for us. We’re a bit longer in the tooth. We’ve been there, seen it, done it.

Megan: You’ve both referenced that you’re older a number of times today, but you also—maybe not actually conversely—seem to be ramping up.

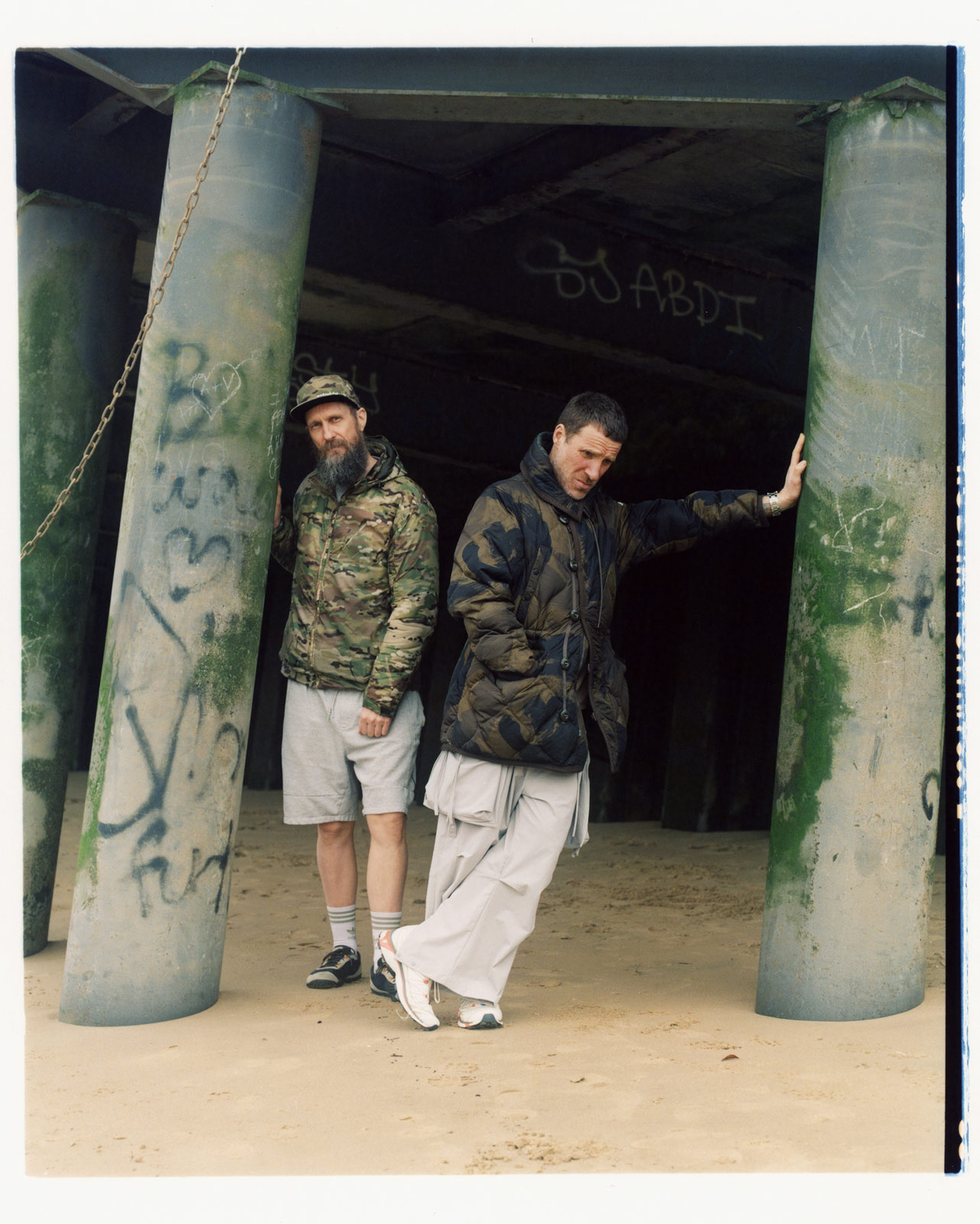

Andrew: We do stand out, in a way, because we’re our age. We were nearly 40 when Austerity came out. We were older when we started. A lot of artists around our age are now fat and lazy and lost it a bit. There’s no one our age still telling it to the man, or whatever.

Jason: Everyone our age is just caught in the period that they became famous in, I suppose.

Andrew: Even when you reach for it, the industry is kind of like, We’re ready to put you in the bin. They want younger and younger pop stars. They’ve been doing that for the past 20 years—it just gets younger and younger. It doesn’t really work very well. It’s not made good artists.

I guess when you’re famous in your 20s or your mid-20s, by the time you’ve hit 35, you’ve been doing it for 15 years. You’re probably just living on a farm somewhere and chilling out. I hope we keep going. We’ll keep going until we drop dead on-stage.