The photobook portraits the quiet pleasures of interspecies affection, unfolding from physical, intuitive communication among two women and the animals they live with

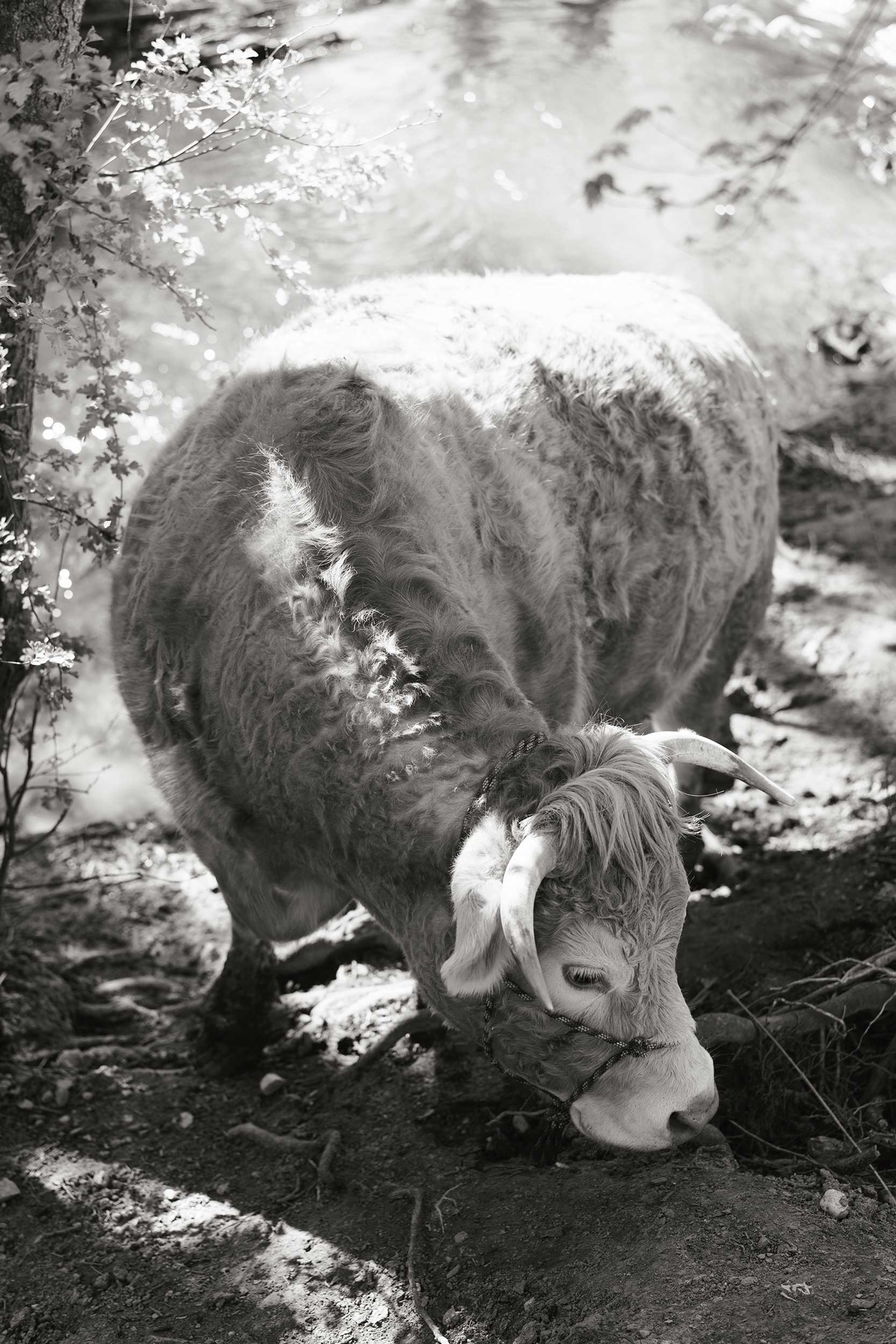

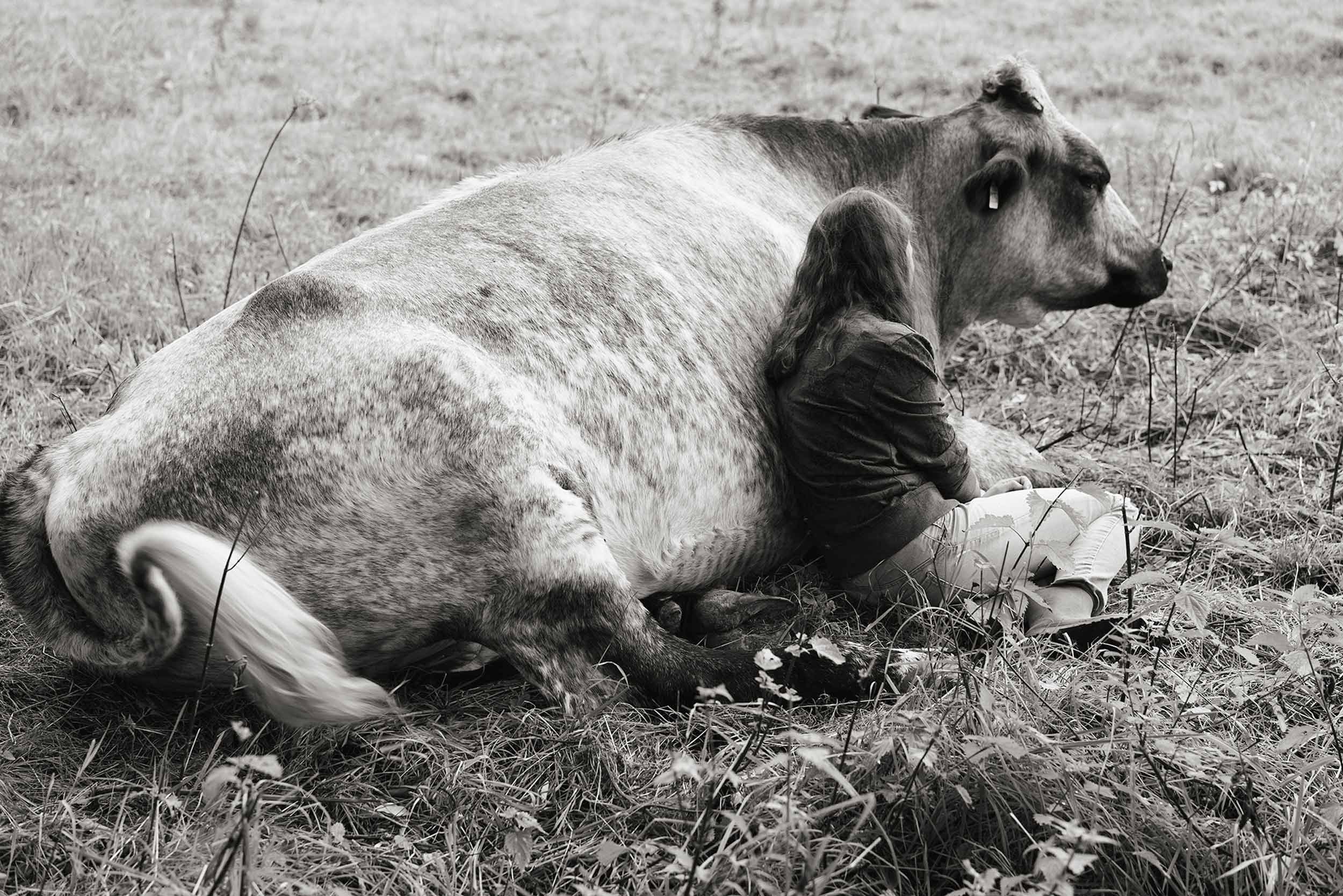

The flopping ears of a pig at play, swirling hair decorating its belly. A cow’s back ridged like a mountain range, its immense weight pressing against the ground. Yana Wernicke is preoccupied with the softer details that characterize animals; with subversions of species loneliness; with the tenderness possible in their relationships with people.

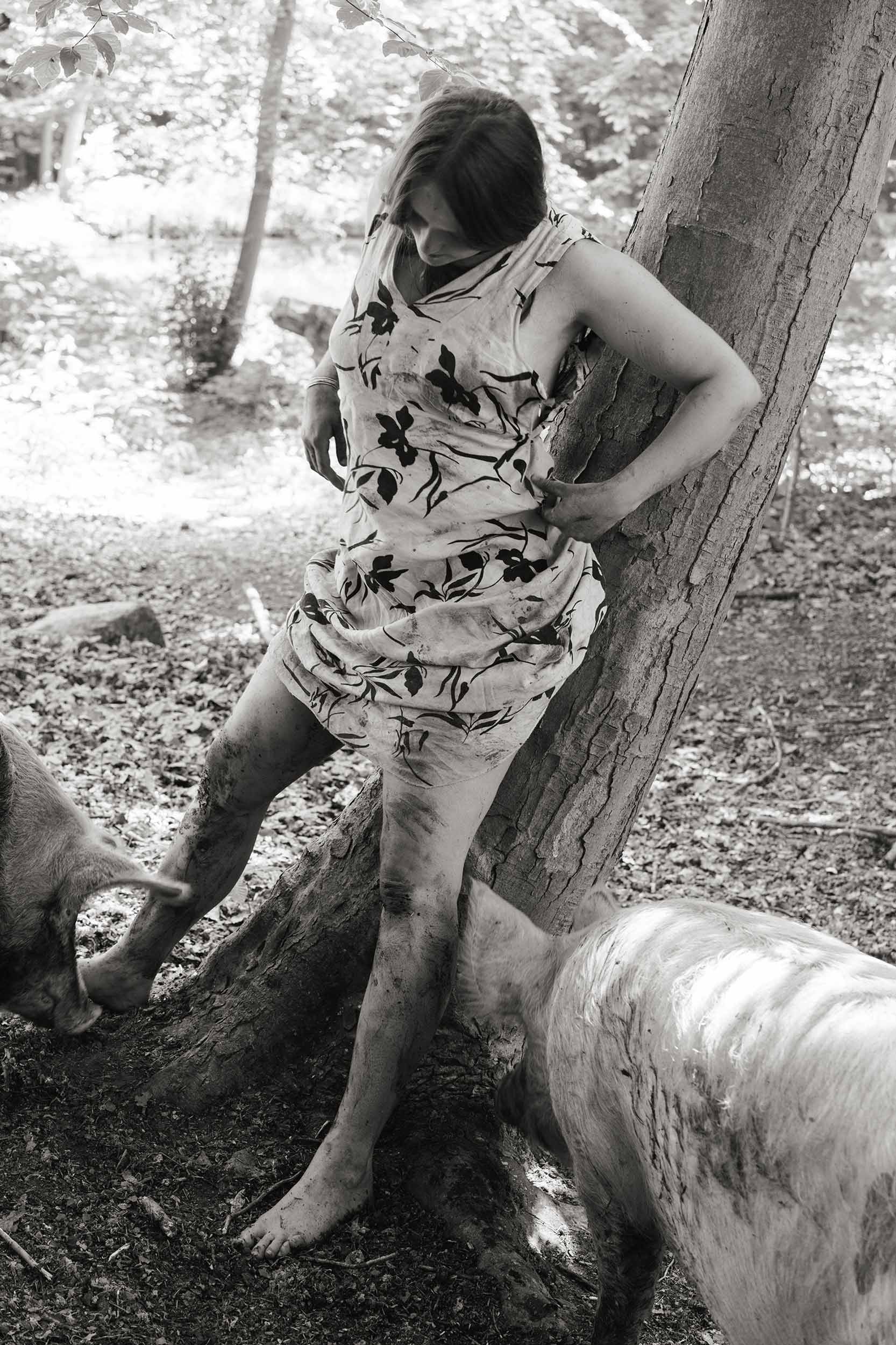

Companions traces that tenderness. The photobook portraits the emotional bond between two young women and the animals they’ve rescued. In German, its title translates to weggefährten, meaning “those who walk the path together.” Wernicke captures the range in types of companionship that the women, Rosina and Julia, developed with the farm animals they live alongside; they mimic those of siblings, of parents, of teachers, of students, of friends. Central to all is a mutual trust, a vulnerability, an eager affection.

Ahead of Companions’s release via Loose Joints, Wernicke joins Document to reflect upon the making of the book, and how its creation furthered her understanding of the importance of interspecies empathy.

Megan Hullander: How did you first connect with Rosina and Julie? What drew you to them?

Yana Wernicke: I had wanted to work on a project about human-animal relationships for a long time. In the beginning, I visited many animal sanctuaries all over Germany, where I photographed the animals and their caretakers.

I met Julie in the summer of 2020. She suggested that I should also meet Rosina—whom she had not yet met herself at that point. I started visiting both of them over a longer period of time and slowly realized that I wanted to focus the project on them.

Both of these women took on the huge responsibility of caring for these animals with little to no outside support. Their friendships with the animals they care for were unlike anything I had witnessed before. Not to say that the people in other sanctuaries aren’t also doing important work, of course—but I think because Julie and Rosina are doing this all on their own, and because their lives are so intertwined with those of their animals, they have such special relationships with them. There is so much trust and tenderness there, but also a huge amount of responsibility and pressure.

Megan: What was your own relationship with the animals depicted in the book like? Did those relationships feel separate from, or distinctly intertwined with, your relationships with Rosina and Julie?

Yana: My personal relationship to these animals is very much shaped through Julie and Rosina, and—to be honest—I never got to develop too close of a bond with them.

Of course, there are some that I connected with a little more—for example, Alvar and Kjell, the two pigs who I got to see grow up over the course of this project. Rosina rescued them from a factory farm when they were very young and I got to meet them only two weeks after they moved into her living room. Every time I visited, I could see how quickly they both grew and how their personalities became more apparent, until they had to move out of the house and onto a pasture.To truly build my own relationships with the animals, I would have had to spend much more time there, and so I saw my role as that of an observer, fascinated by Rosina and Julie’s way of living with their animals.

“Maybe humanity’s arguable loneliness stems from the fact that we have forgotten to communicate the way that animals do. Maybe our intraspecies communication has become too rational, instead of physical and intuitive.”

Megan: There’s a physical intimacy to many of the images in this collection. How does physical touch define or help you understand a person’s relationship with an animal?

Yana: Touch seems to be the primary way of communicating with an animal in a more intimate way. Touch between animals and humans is complex. Especially when you look at animals rescued from a farm, they might not know that human touch can also mean something positive—something not to be afraid of, but a declaration of friendship and companionship.

Both Rosina and Julie are very physical with their animals. There is touching, caressing with hands, but there is also just bodies leaning against each other, enjoying each other’s warmth and company. Their animals seek out this kind of physical attention.

Every relationship is different, though. Some are more physical than others, and Rosina and Julie are very respectful of their animals. Some might have had bad experiences in their time as ‘livestock,’ and so they will of course be approached a little more cautiously than the others.

Megan: Are there ways in which man’s relationship with animals can transcend those with other people?

Yana: I’m not sure if they can transcend relationships between people, but they are certainly different. Mainly, I think, because they are not based on language. Sometimes, I wonder what humans could gain in terms of understanding if we gave up language for a while and rather used just sound and our bodies to communicate with each other.

I think this is also where the concept of species loneliness comes into play, which is very much at the heart of this project. It is this idea of a longing, a nostalgia for a world in which humans find their way back to a life that is more entwined with that of animals. Animal-human relationships can be humbling; they can make us become aware of our own animal selves and feel a closer connection to the natural world.

Maybe humanity’s arguable loneliness stems from the fact that we have forgotten to communicate the way that animals do. Maybe our intraspecies communication has become too rational, instead of physical and intuitive.

Megan: Why did you choose the title Companions?

Yana: When I asked Julie and Rosina how they each would describe their relationships with their animals, their answers were very complex. Some they see like a brother or a sister, others as a daughter or son, and even as their teachers or students. These relationships are not fixed, but ever-changing.

But [there is] one thing they all have in common: They accompany each other on a stretch of their life. They are companions. In German, the word for companions is weggefährten, which translates to ‘those who walk the path together.’ I like this idea of sharing a path, of walking next to each other or following each other—without hierarchy. Companionship goes both ways.

Megan: Many of the images included in the book are very textural—is there a narrative or ideological function to that? Your eye seems drawn to the bodies of animals.

Yana: I think it’s both. As I [said], communication with animals is very much based on touch. I wanted to make this physical experience somehow tangible in my photographs. That’s why there are a lot of photographs of fur, skin, and body parts touching. I wanted the photographs to translate the closeness of this experience, so that as a viewer, you might feel the sensation of touch yourself.

We have become used to seeing these animal bodies as flesh to be consumed. But I wanted to show them as they truly are: living creatures that can feel pain and enjoy tenderness.

Getting so close might also reveal similarities between their bodies and ours. Pigs especially have had a really bad reputation for centuries, but they are actually such intelligent, lovable creatures. I suspect that the reason we often look down on pigs might be that their bodies, and especially their flesh, are so similar to ours.

I enjoy looking at animals closely, in all their physicality. The ears of a pig flopping around when it is playing—just like my dog’s. The swirls of the hair on a pig’s belly. The immense weight of a cow, the way their bodies turn into mountain ridges when they lie on the ground. They could crush you in an instant, yet they are so gentle and careful. Not to sound too romantic, but nature really provides endless space for such discoveries and observations.

Megan: Where did this project alter your own understanding of human-animal relationships?

Yana: A couple of months before I met Julie, I adopted a dog from a Spanish kill shelter. I absolutely love her, but she is also very difficult and still struggling with the environment she was brought [from]. Experiencing the relationships and the acceptance that Julie and Rosina have for their animals helped me to see things from my animal’s perspective, and in gaining an understanding of her. We all have the capacity for more empathy toward the non-human world.