Following his Paris Fashion Week debut, the designer joins Document to expound upon the evolution of his practice, embracing material corruption, and imagining new forms for the abstract

Inside Paris’s Galerie Perrotin, Daniel Arsham cracks apart a plaster-cast sculpture, revealing a plaster jacket, which he places on a model, who is already dressed in plaster pants.

There is an instance, for any decent designer, where their work transcends functionality and is labeled as art. But with Arsham, that classification is much more literal and refined than usual. His works are equal parts garment and objet d’art; they could stand alone as sculptures, but also—as proven in his Paris Men’s Week show—they’re wearable.

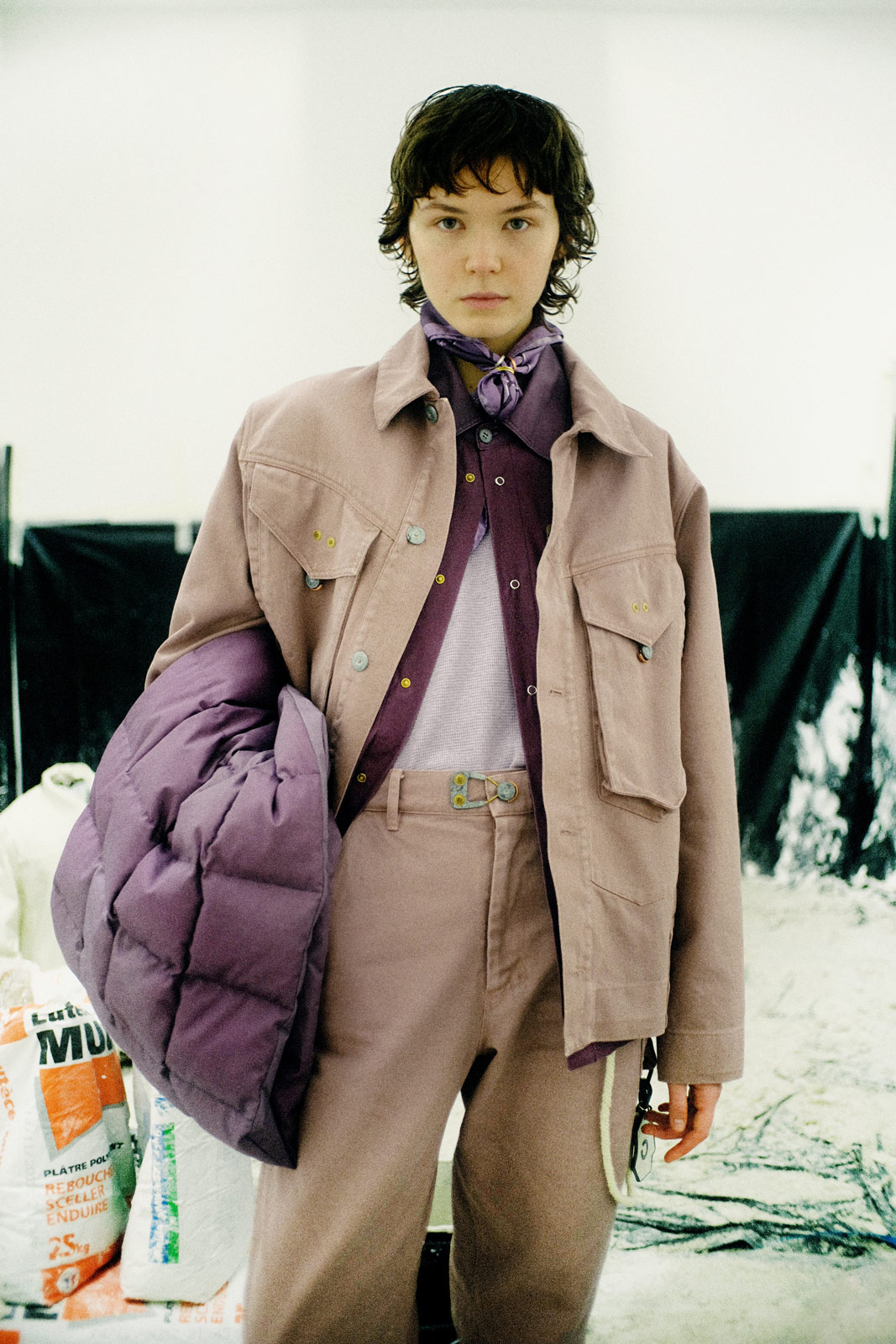

Arsham built Objects IV Life Chapter .003 with the intent of manufacturing a uniform for artists—a wardrobe that shares the creative impulse of the work they create. Riffs on workwear staples are imagined through the lens of Arsham’s fictional archaeology, which marries tradition and modernity: bold prints directly inspired by land-art installations, boots with uncoated metal toe caps built to decay, garments covered with an outer layer of fabric that is designed to dissolve with each wear. “The expectation that garments will stay perfect forever is impossible,” Arsham muses—his collection proposing to capitalize on their inevitable degradation, applying it intentionally.

Following his Paris Fashion Week debut, the designer joins Document to expound upon the evolution of his design practice, embracing material corruption, and imagining new forms for the abstract.

Megan Hullander: How does your sculptural practice translate to designing wearable garments?

Daniel Arsham: Sculpture is probably what I’m most known for now, even though painting was what I studied in school. Sculpture, and art in general, is something that we typically experience from the outside—we view it and we experience it without touch. But clothing houses us, changes our character, changes our physical shape. So, in a way, this entrance into the creation of garments allows the audience to kind of sculpt themselves.

Megan: This collection was built for the needs of the artist—how do you define those needs, whether that be in terms of functionality or aesthetics?

Daniel: In the beginning, for all the pieces, we start with functionality. Obviously, the clothing serves a purpose, and a lot of it is about the wearability of it, the durability of it. There’s a lot of denim, the steel toe caps on the boots, safety in the studio, lifting and moving heavy objects. But within that, there’s the possibility to allow for patina to happen. All the hardware in the garments is untreated, so it will patina with age, allowing the garments to have this kind of evolution of design and life.

Megan: How does this third chapter of Objects IV Life further cement the brand’s DNA? How has it departed from its initial conception since its genesis?

Daniel: Chapter .003 is really the most developed, in terms of outerwear. A lot of the silhouettes remain the same from Chapter .001, but the materials have advanced. We’ve had the introduction of responsibly sourced down jackets, as well as the Casentino jackets and gilets. The signature dungaree hardware has been increased in scale and used in bags. There are straps on a lot of the clothing that allow [for the] connection of bags to those pieces, and I’ve taken inspiration from vintage camouflage with some of the garments, to add this kind of abstract patterning.

Megan: How does your fascination with decay inform your approach to making garments that are built to last? How do you anticipate these pieces will evolve over time?

Daniel: I think the expectation that garments will stay perfect forever is impossible. So, the idea is that they will patina and age and change with wear, with intention.

“Clothing houses us, changes our character, changes our physical shape. So, in a way, this entrance into the creation of garments allows the audience to kind of sculpt themselves.”

Megan: In designing for this collection, did you begin with form or material? Were there any references or inspirations that felt particularly formative in the ideation of it?

Daniel: I’m not a trained designer in that way, so the translation of ideas into garments is done through our in-house designer, Matthew Grant. A lot of it begins with vintage pieces from my own collection, and things that I’ve found over the years that had a shape that I liked. I may give him a sample of fabric or a sketch of an idea that we test out—all of it has begun that way.

Megan: How did you go about constructing the soundtrack for this show? How does it play off your designs?

Daniel: I began playing around with this Teenage Engineering OP-1 synthesizer a couple of months ago, and reached out on Instagram to my community, to see if somebody who was a producer could help me refine that sound. Crooklyn was one of the people who responded to my message. I played everything that was heard in the presentation, and he helped adjust it. He added the bird sounds at the beginning—it’s a subtle sort of 808, with synthesizer keys in the background. Really, it was just about creating a kind of environment for the Chapter .003 collection to exist within.

Megan: Why did you select Galerie Perrotin as the site for this show? What excites you about fashion within the context of art?

Daniel: It was not an accident. My first ever exhibition happened 20 years ago, at that exact same location, in that same room. The idea of presenting sculpture, that was then literally broken, to reveal this new chapter, was something special. I had created a number of sculptures of these jackets in the past, so many people who were at the show were familiar with them. I think it was quite a surprise when they were broken out and became these wearable objects.