'Et In Arcadia Ego' explore the ephemerality of the controversial practice, chronicling its landmarks and modern audiences

“He doesn’t fight to defend anything, but fights from pleasure having been bred to do exactly that,” said Orson Welles in episode six of Sketch Book, an installment dedicated to toro bravos, Spanish fighting bulls. A few minutes before, Welles noted, “The institution of bullfighting, you know, somebody once described as being indefensible… and irresistible.” These words were the breeding grounds of photographer Oliver Eglin’s latest series, Et In Arcadia Ego, a pensive portfolio that explores spectatorship and the prevalence of violence in history.

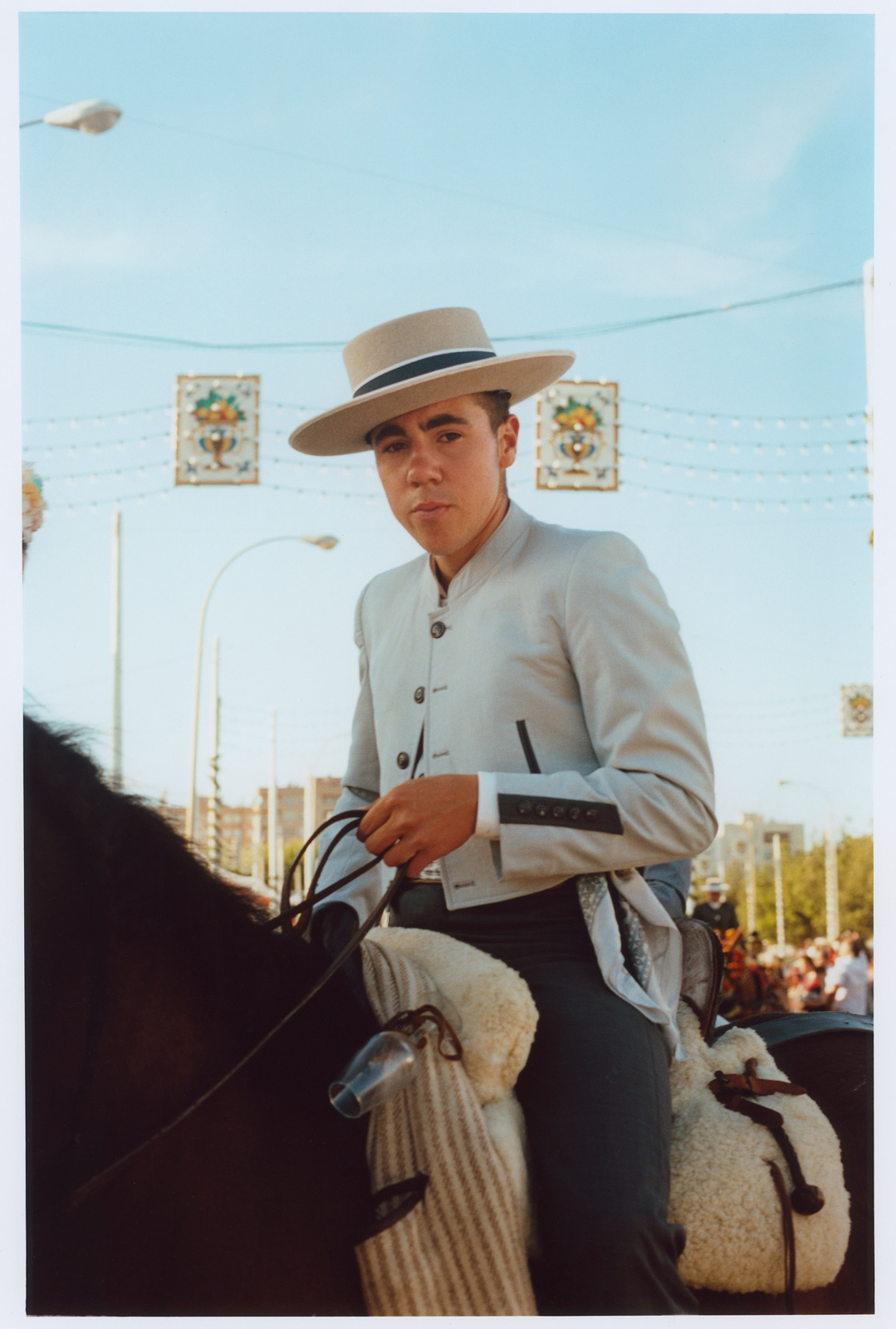

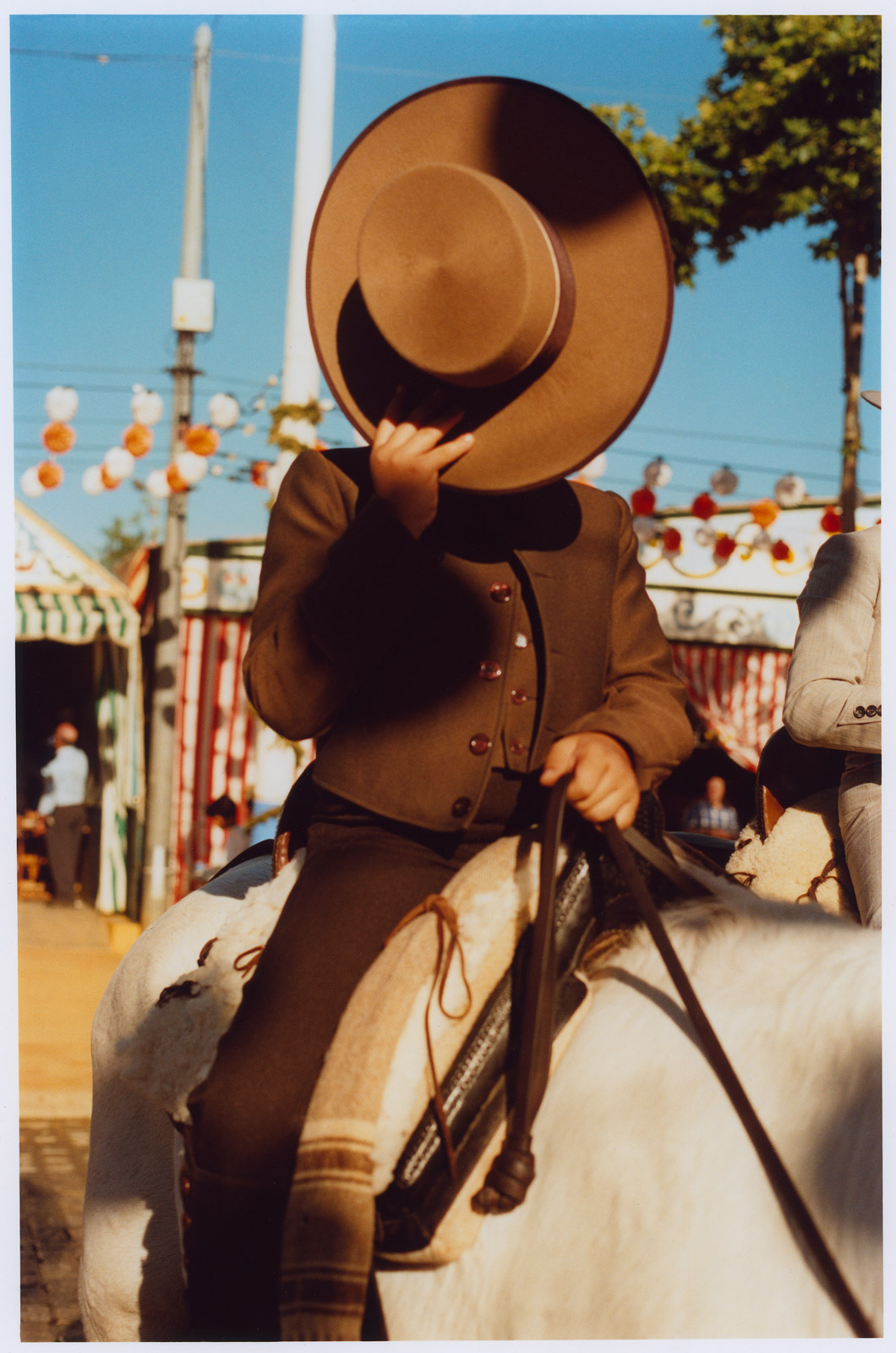

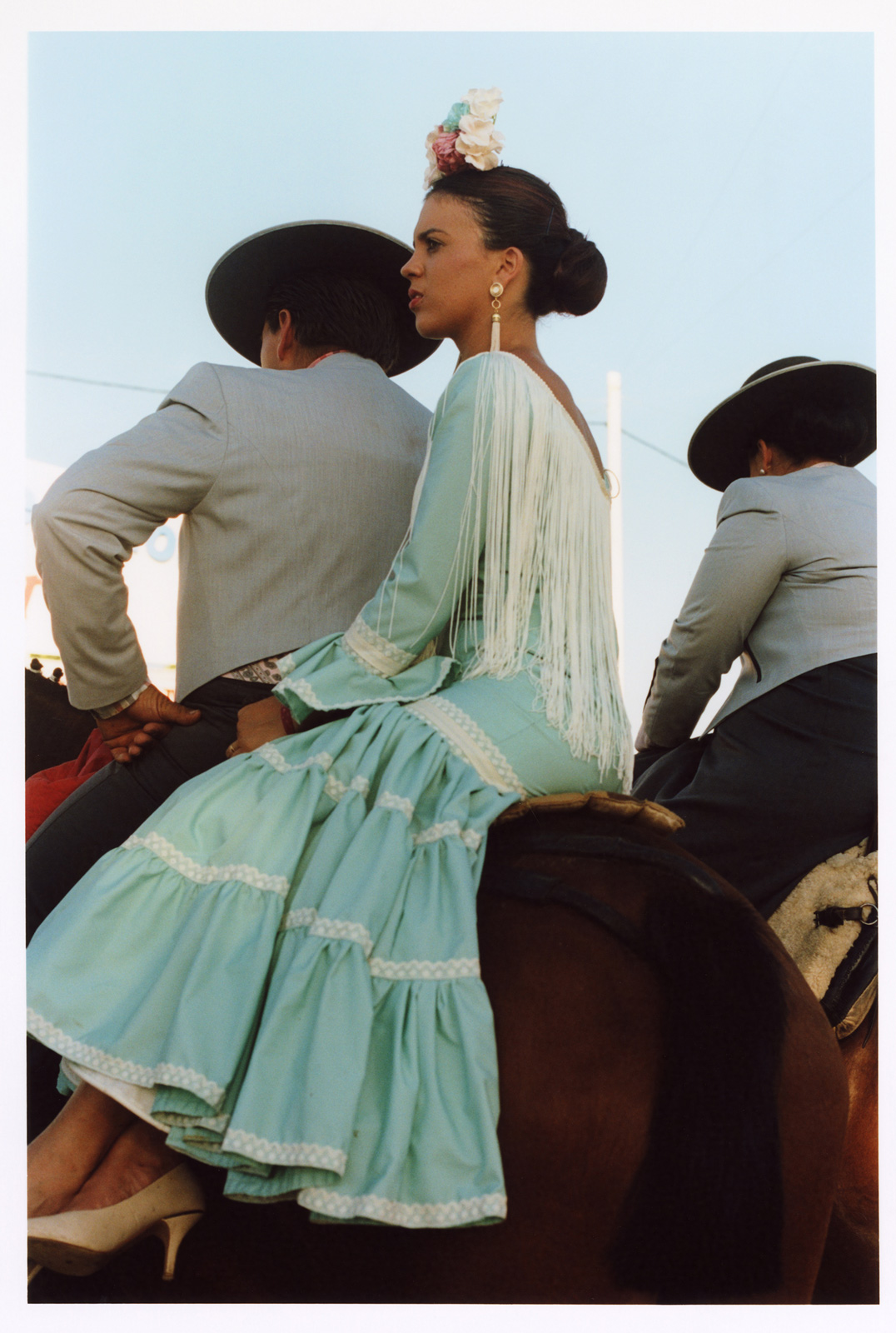

The Welsh visual artist works at the intersection of natural and urban spaces, of culture and the surrounding environment. For Et In Arcadia Ego, Eglin investigates the ephemerality of human civilization, and its lasting imprint on ruins through bullfighting, which take form in his documentation of structures like the ancient Roman amphitheater Italica. He’s well aware of the controversy behind the art and sport, consciously choosing to decipher its voyeuristic side. But Eglin steers clear from conventional brutal action shots, instead transforming the audience, matadors, and lonesome bulls into his muse in scenes from La Feria de Abril, a two-week tribute to the blossoming of spring.

Consistent with the broad timescales typical to his practice, this project was built over the course of a few years. Every visit to Seville allowed Eglin to further refine his work. Splashes of vibrant reds are woven into earthy tones, offering a glimpse of the Old World tradition. The stadiums and landscapes are rigid, the faces of people and animals are soft. Taken as a whole, the series tells the story of a centuries-old practice that has endured to this day.

Eglin joins Document to discuss his journey across the south of Spain to Andalucia, where he captured the region’s long-standing infatuation with the sport.

Madison Bulnes: What first drew you to bullfighting?

Oliver Eglin: I was drawn to a series of photographs of Picasso at the bullfights in Arles—I was fascinated by how captivated he looked. From there, I started researching [the tradition of it]. Eventually, I decided I wanted to explore the subject for myself. I made a trip by train from Paris, down through the center of Spain to Andalusi.

Madison: Why did you choose bullfighting as the medium through which to discuss humanity’s imprint on the world?

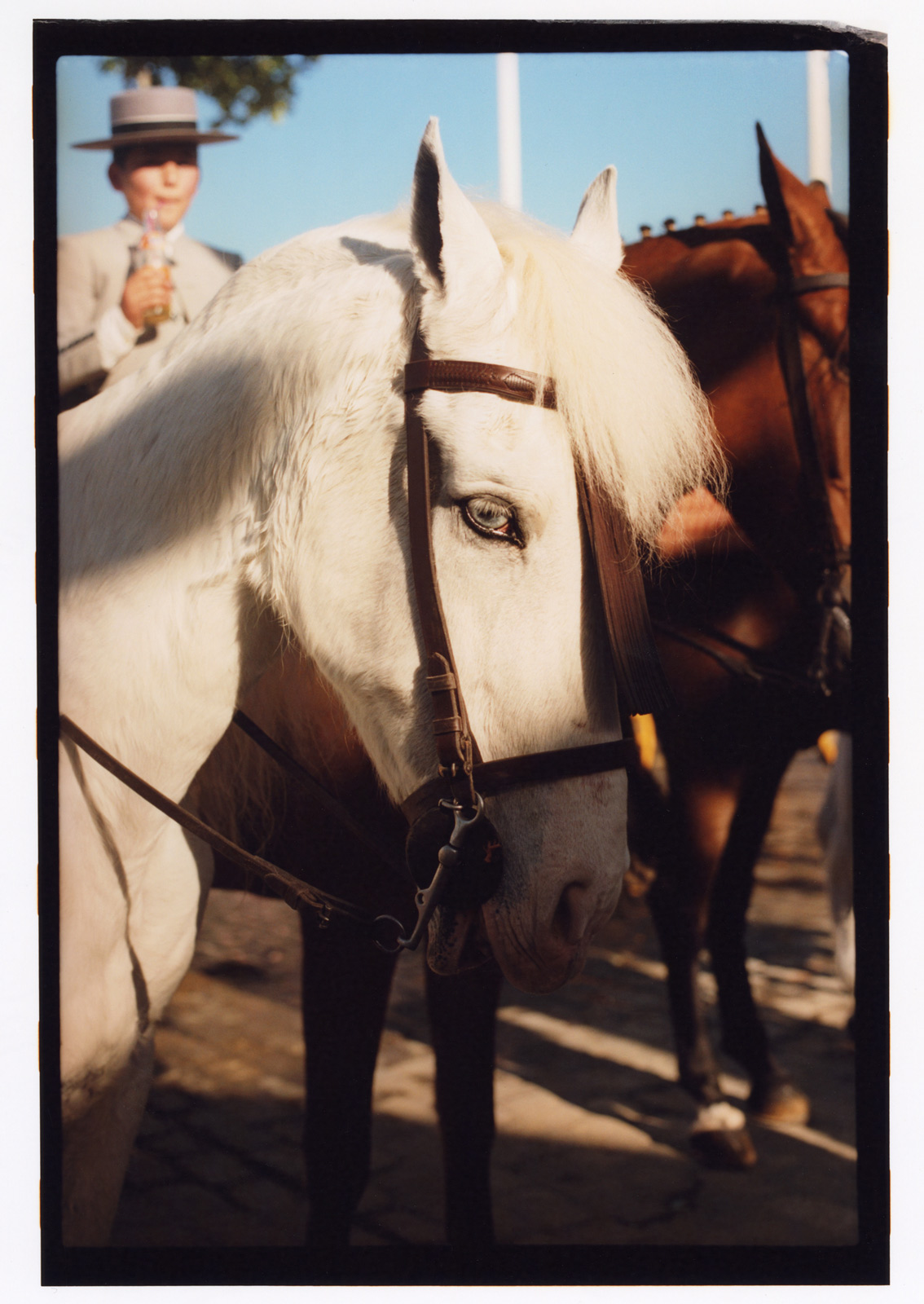

Oliver: My initial feeling was that bullfighting is just totally anachronistic. It seemed out of sync with modernity. Yet, in Spain, it’s a part of life. I’d been thinking a lot about humanity’s relationship with nature and the balance between them. Bulls, visually, are beautiful animals, but their form is shaped by the sport. The Spanish fighting bull is unlike any you would find in domestic livestock; he is much wilder and more aggressive. Humans have revered bulls throughout history, and I was interested in how—through studying our relationship with these animals—I might say something about our imprint on the world.

Madison: What was it like to attend La Feria de Abril festival?

Oliver: La Feria is a uniquely exuberant party—a whirl of color and energy lasting almost two weeks. Dresses, horses, and sherries [are at its center]. In the evenings, people dance and listen to flamenco performers. There is a connection between the bullfights and La Feria, but each event retains autonomy from the other.

Madison: What cultural customs stood out from the week’s celebration?

Oliver: I want to look at the preparation leading up to the bullfights, which ordinarily would go unseen. The bulls arrive at the arena on the day of a fight. Then they are shown to a private audience inside a coral. Afterward, the torero’s assistants draw lots to find out which bulls will face that evening. It is all very tense—no one is allowed to speak for fear of agitating the bulls. I came to appreciate the majesty and sheer power of the bulls after seeing them at close quarters.

Madison: You focus on two types of ruins in this project: historical remains, like the ancient Roman amphitheater and contemporary places, like the bullfighting rings. How do they compare to one another?

Oliver: Italica, the ruins of a Roman settlement on the edge of Seville, is where I made a section of the work, as I wanted to explore how that legacy bears relevance today. The connection is obvious; these ruins were the scene of gladiatorial fights some 2,000 years ago. Even if the history of a bullring is more recent, its design references the form of Roman amphitheaters. There is something deliberate about bullfighting resisting time, and it was interesting for me in terms of creating work that fractures or disrupts linear narratives.

Madison: Your photographs often look like they were taken secretly. Do you prefer to work as a spectator?

Oliver: Bullfighting was quite an abstract concept for me. Bloodsport exists outside of Spain, of course, but it doesn’t occupy such a culturally prominent space. Naturally, my perspective was that of an outsider looking in, but it wasn’t something I cultivated consciously. The work is [itself] about spectatorship—why these events draw in crowds of people, and what it is like to be a part of one. Iconic images of bullfights tend to be close-up action shots. I wanted to subvert this by focusing more on the audience and the apparatus around the event.

Madison: Where does your interest in ruins come from?

Oliver: Auguste Rodin said, ‘More beautiful than a beautiful thing is the ruin of a beautiful thing.’ It’s something I have long considered when creating work. I’m interested in the inevitable propensity for architectural and cultural upheaval, and nostalgia for what remains of the past. The cultural origins of bullfighting are tied in with the legacy of gladiatorial combat, so it seemed relevant to include aspects of Seville’s Roman history.

Madison: What do you hope to capture with landscape photography versus portraits—and in this case, portraits of bulls?

Oliver: I don’t particularly think about creating portraits or landscapes; it’s more about the project as a whole, and how I want to develop a narrative within the work. There are photographs where the bulls turn to look at the crowd—I find these moments to be powerful. It was a way to put the focus back onto the audience, as I wanted to implicate the viewer in thinking about how violence, and ultimately death, assume the form of spectacle.

Madison: What are your feelings on the controversy behind bullfighting, and have they changed over the course of this project?

Oliver: My feelings haven’t changed much. I had little interest in making a value judgment about bullfighting. The violence is self-evident—I was more interested in [exploring] what it is about that appeals to people. My understanding is that there is something about the proximity to death that has a cathartic effect on the spectator. Orson Welles described bullfighting as both “indefensible and irresistible.” I think that’s a good summary of how it has resisted reform.

Madison: Why did you decide to name your project a Nicolas Poussin painting?

Oliver: Et in Arcadia Ego is the title I took from a work by Guercino, which Poussin referenced in his own painting of the same name. Essentially it depicts a memento mori: two shepherds have arrived upon a human skull, which suggests the ever-present nature of death. Even in Arcadia, am I is the translation from Latin—I liked this juxtaposition of the Feria as a kind of Arcadia, alongside the bullfights which depict death.

Madison: What do you hope to say about the ephemerality of human civilization with this project?

Oliver: The work is about the myth of cultural progression, the idea that somehow we are more civilized and less bloodthirsty than we once were. History is not linear, we are bound to repeat ourselves, and I wanted to convey this thought through my photographs. Our world has become more precarious recently, and I think it is worth remembering that many great civilizations, ultimately, fell.