For Document’s Summer/Pre-Fall 2022 issue, the master storytellers talk ‘Aliens,’ ‘Avatar,’ and surviving the chaos of filmmaking

The written word holds immense power. Good storytelling conveys ideas, incites change, and challenges us to explore philosophical and moral questions about humanity’s past, present, and future. James Cameron is mostly known as a masterful director and pioneer of special effects, but he’s also an epic storyteller. Still, when the then-upstart filmmaker was tasked with writing a sequel to Ridley Scott’s Alien that centered the character of Warrant Officer Ripley, he didn’t expect to find himself in the make-or-break position of presenting his story to one of Hollywood’s toughest critics: Warrant Officer Ripley herself.

Sigourney Weaver, an English major and Yale Drama-trained actor, had little interest in science fiction, let alone returning for a sequel to the sci-fi horror blockbuster that had put her on Hollywood’s A-list. (A self-confessed theater snob, she claims to have gotten through her scenes in Alien by pretending she was performing in Shakespeare’s Henry V.) Luckily, Weaver was astonished by the complexity and structural merits of Cameron’s script—and he was receptive to her input on the film’s dialogue and the drawing of its central character. Aliens became the first, and probably only, sci-fi action masterpiece about motherhood and the Vietnam War. Weaver—a gun control advocate whose only brush with violence was almost getting into a fistfight arguing between Fitzgerald and Hemingway in college—became the first to receive a Best Actress Oscar nomination for a sci-fi movie, cementing Ellen Ripley as one of the most groundbreaking female action heroes in cinema history.

Weaver grew up in New York City during TV’s golden age, raised by parents who were part of a scene of postwar entertainment pioneers. Her mother, Elizabeth Inglis, was an English actress, and her father, Sylvester “Pat” Weaver, was a television executive who served as president of NBC and created the Today Show. In the days before home video, films wouldn’t be seen unless people saw them in theaters, and perhaps this—along with her father—instilled in Weaver a powerful sense of which stories would survive what she calls “the chaos and bloodshed of filmmaking.” After Aliens, Weaver proved her versatility with an assortment of critically-acclaimed projects including The Year of Living Dangerously, Ghostbusters, Gorillas in the Mist, Working Girl, and Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm, as well as contributing voice work to Futurama and WALL-E and narrating the American version of the BBC’s Planet Earth. Meanwhile, James Cameron was developing a project called Avatar, which he planned to start filming after he finished Titanic in 1997—however, he would have to wait 10 years for technology to catch up with his vision. Eventually, Weaver and Cameron revisited their collaborative working relationship and shared enthusiasm for field science when Weaver was cast as Dr. Grace Augustine, an exobiologist and head of the Avatar Program, who advocates for peaceful relations with the Na’vi, a humanoid species indigenous to Pandora. A visually hypnotizing science fiction epic that interrogates colonization, corporate interests, and our relationship with nature, Avatar remains the highest-grossing film worldwide. The first of four sequels, Avatar: The Way of Water is slated for release in December 2022 and sees Weaver return as a different character. As Cameron says, “No one ever dies in science fiction.”

Sigourney Weaver: Hi!

James Cameron: There you are, looking so radiant.

Sigourney: Oh yeah, right. How are you? It’s been forever.

James: I know. Well, it feels like forever. Every day feels like forever. It’s like a hamster wheel that I can’t get off of.

Sigourney: You mean the film itself? Or life?

James: Yeah, I’m talking about Avatar, not life in general. You get to sort of flounce in and do a bit of acting from time to time.

Sigourney: Sometimes I think I’d like to be in your role.

James: You’d be great at it, actually.

Sigourney: Not for Avatar.

James: No, no, no. Not that kind of movie, but you should think about directing. Everybody would be terrified of you, they’d do exactly what you say even if it was wrong. You’re so well-read, and you know all the novels, you know all the plays.

Sigourney: Well, I always wanted to be a writer. They hold the keys to the city. I think that I found it too lonely, I’m much more of a team player. But, you know, I’m beginning to feel slightly fulfilled in my career, and maybe that means I could take on a different challenge.

When I was sent your script of Aliens, I was working on a film in France with Gérard Depardieu, and I [found it to be] this full-blown, remarkable story that had such a strong theme, such a powerful emotional story. It was so touching, it was so funny. It also had—which impressed me to no end, because most film scripts don’t—an amazing structure. You had my character—who had survived, but who knew what would happen to her if she floated around in space—beginning as someone mocked, someone not listened to, someone discarded, tossed away. I thought it was such an amazing beginning for that character, because obviously, going through something like the first experience of Alien, she would have changed every cell in her body.

James: Well, we were telling a story about a traumatized person. You became a kind of feminist or post-feminist icon out of that film. And, as you describe it, it occurs to me that part of it was because they didn’t listen to you. And you can attribute that to gender. I mean, yes, your story was outlandish, but the subtext of it was they didn’t listen. The male power structures, the business guys, the corporate guys, the corporate tribunal, the military guy—they were all male-dominated, patriarchal power structures, and they didn’t listen to you.

“I feel like shooting can wear down a story. It can defeat the story. It has to have a strong enough structure to stay standing after the chaos and bloodshed of filming.”

Sigourney: I get pissed off just thinking about it [laughs].

James: The funniest review I ever heard of Titanic was from a guy standing in line at a theater, who said to his pal, ‘It’s a chick flick with guy parts.’ I think that applies to Aliens. There’s plenty of gun-and-run, ‘Hurry up, the bad guys are coming through the door,’ kind of stuff—the jeopardy. But there’s really this subconsciously architected feminist statement there. I wasn’t even aware that’s what I was doing.

Sigourney: I think you pitched David Giler and Walter Hill doing another Alien, didn’t you? How much of it had you already conceived? Any of it?

James: I was pitching a story to David and Walter—they had really liked my Terminator script, and this was before I’d actually shot Terminator—they liked me as a writer. I went in and I pitched my heart out on this thing that they wanted to do, which was Spartacus in space. I had this whole idea about genetic engineering and this slave class and this elite class, and they said, ‘Yeah, but there’s no swords.’ I said, ‘What?’ I was taking Spartacus metaphorically, I wasn’t taking it literally. They said, ‘No, we want a sword and sandal epic in space.’ I’m like, ‘Oh. Okay, that’s super disappointing.’ So I basically got up and threw myself out of their office. I was out in the corridor and a guy said, ‘Wait, wait, wait. We got this other thing.’ I said, ‘What is it?’ And he said, ‘Alien 2.’ If you could have taken a brain scan of my mind at that point, it would look like a pinball machine lighting up. I wrote the treatment in, like, three days, because I took this other thing I’d been writing called Mother. It was originally called E.T., but some other guy beat me to the title, so I changed it to Mother. It was about, basically, two mothers battling to the death across two species. I just dropped Ripley into the middle of the story and moved it from Venus, where it was supposed to take place, to the planetoid.

I was petrified when I drove up to Santa Barbara to meet you for the first time. I thought, I’ve signed on for this thing, and I know nothing about this woman. This was before the internet, where you can Google everybody. I think you had done A Year of Living Dangerously, but that hadn’t come out, so all I knew was Warrant Officer Ripley. I knew you were tall. This was my second film, but it was my first film with a movie star. I’d done Terminator with Arnold, but for some reason, Arnold and I just clicked. I had no idea what to expect from you.

Sigourney: I’d have much less of an idea of what to expect from Arnold Schwarzenegger than I would from a regular actor.

James: I always assume that it’s a collaboration that could become a power struggle. I walked in thinking, If she’s wearing tall heels and wants to tower over me and intimidate me, then I’m screwed, and if she’s wearing flats she’s too self-conscious about her height. You were wearing, like, a medium heel, and I went, Okay, so far I’m good [laughs].

Sigourney: I’m sort of astonished you gave it that much thought. What I remember about meeting you was how terribly nice you were, how interested you were in my point of view—you certainly weren’t one of those guys who didn’t think an actor had a brain. You were very interested in what I thought, you wanted it to resonate for me. I was already smitten, because I had read the script and I just could not believe how you could come up with all those different levels of relationships—it was just so complex, and yet it was so simple.

James: I remember we clicked right away over the material. There’s a picture, one of the behind-the-scenes pictures, it’s actually my favorite from the whole production—and it’s you and me sitting on the ramp of the dropship set, and we both are like this [makes a concentrating face], and we’re just deeply in it. The whole crew is standing there waiting while we figure it out. That’s my memory of our working relationship, which is that we just sat down and we talked it out. At first, I was worried that you approached everything a little too intellectually, and then I saw you work. You were able to go straight to the emotion so deeply and thoroughly and quickly. You always had a sense of perspective, a kind of overmind, but you were also able to be a hundred percent intuitive in the moment. I came out of that movie thinking, That’s what actors should be. Then, to my disappointment, I found out that they are not all that.

Sigourney: What’s funny is either I’m lazy or I know my limitations, because I can find a script, as I did with Aliens, that’s about something more than the people in it, that has a very strong story that’s really about something, that has humor, and that has a structure—because I feel like shooting can wear down a story. It can defeat the story. It has to have a strong enough structure to stay standing after the chaos and bloodshed of filming, and I knew that yours would. That gives an actor, at least an actor who’s an English major, tremendous confidence. I can’t ruin this picture. This picture will work no matter what we do. It’s sound.

James: Unfuckupable is the word I prefer.

Sigourney: Yeah, unfuckupable, exactly.

James: And you had to look forward to shooting machine guns. We had one disagreement on the film, and you came to me and said, ‘I’m very concerned. I’m a gun control advocate, I can’t shoot a machine gun, I’m sorry.’ I said, ‘Did you actually read the script? This woman goes berserk.’ [Laughs] As my memory serves—and I’d like to cross-reference with yours—I said, ‘I’ll get some weapons, we’ll have the armor set up.’ We had them set up behind the James Bond stage. We were way out in the back of the back lot at the studio. I remember he handed you a Thompson submachine gun, and you just held the trigger down and went Brrrat-a-tat-tat, like that. There was this kind of stunned look on your face, then you looked over at me and kind of smiled, and said, ‘I can do this.’ [Laughs] Another liberal bites the dust.

Sigourney: [Laughs] I know, really. So much for my ethics. That’s a very powerful thing, unfortunately, to hold a machine gun.

“What I think is so exciting about the sci-fi space, and why it continues to be relevant, is that the things that come up in these movies are things that kids are really worried about.”

James: I’m questioning it more in my later professional life. If I were to make another Terminator film now, I don’t even know how I would want to approach it. That’s a hypothetical, but those movies are about guns. To me, the gun in Aliens was never the gun, it was the power loader—it was a symbol of technology and something that could be used as a tool or a weapon, and in my mind it was symbolic of how we always weaponize everything. We’ll figure out a way to weaponize advanced AI—the second we get a computer that’s as intelligent as we are, it’s going to be a weapon.

Sigourney: And those poor soldiers, they had machine guns, but they were worthless against this foe.

James: Right. And in my mind, that was all a metaphor for Vietnam. We sent in all this heavy horsepower, all this heavy weaponry, but we were outsmarted and outrun and outdodged—the classic kind of guerilla action. You can’t just solve a problem with a military sledgehammer.

Hannah Ongley: In Aliens, do you think there was a misreading on the part of the audience about your intentions with the weapons? I just wonder if that criticism of the military industrial complex was something you tried to make more overt in Avatar.

James: I don’t think so. I was very much a creature of the ’80s at that point. There’s a fine line between action and violence. Gale and I set out to make an action film out of what had previously been a horror film, so we kept some horror but we didn’t have that deep, Freudian subconscious, terrifying body horror. We didn’t get to that level—by intention—and we put a lot more action in than Ridley had. But that was a long time ago, and I look at the responsibility of movies differently now. Are there guns in Avatar 2? Absolutely. But I distinguish a lot between what is fantasy in a film and what the social responsibility of a film is. Sigourney and I, we’re both so attuned to what the positive messaging of the Avatar films can and should be. We got such a wave of positive feedback from the first Avatar that we became these overnight eco-crusaders.

Do you remember our trip down to the Amazon, Sig, to try to stop the Belo Monte Dam? Who could forget our time in the Kayapo village?

Sigourney: Oh, I know. [Laughs] Covered with insects, yes. But I’m grateful we got a chance to do that and to meet so many of the villagers. I got to sit with the women. I didn’t understand the language, but I felt that they were very graciously accepting of us as visitors who meant well and were anxious to help. It wasn’t a very long stay, but it was a very powerful one.

James: I look back on it now and I just wish we could have done more. I think we did what we could on short notice, and with relatively little training. We put together a good team and we had good translators—there were literally only two people in the world who spoke Kayapo fluently, and we had one of them. I wound up going back with Arnold, trying to blow it up as a media thing, because I thought, You can’t just do a drive-by. You’ve got to be in it to win it, you know? It’s just—the bulldozers don’t stop. We showed stopping the bulldozers in Avatar metaphorically, but in reality, they don’t [stop]—and under Bolsonaro, it’s even worse. He considers the indigenous to be vermin. He just wants to bulldoze the whole place. It’s horrific. You can only hold back that tide for so long.

Sigourney: I’m very excited about Avatar 2 going around the world, because I do feel like it will start to fan the flames of that unity we felt when the first one was out there playing—how much more we shared in terms of what’s important to us. It really brought us together, Jim, in the most amazing way, and I’m hoping the second one will do even more.

James: We’ll see. It’s a very different picture. I think it’s more challenging in a lot of ways to people, and I was a little worried about us being seen coming in the door with a big target on us, as being those Pollyanna tree huggers. So there’s a strong theme running through it, obviously, of the connectedness of nature, and your character expresses it so beautifully, not so much in word as in deed.

Hannah: Is there something about the science fiction genre that appeals to you in terms of communicating these universal themes of environmentalism, or military intervention? Is there something about that genre that makes you feel like you can appeal to a wider audience?

Sigourney: What I think is so exciting about the sci-fi space, and why it continues to be relevant, is that the things that come up in these movies are things that kids are really worried about—like, that people are like the people in the company in Alien. And now it’s not just corporations, you see politicians acting that way, too. How do you fight against that kind of blindness, deafness?

James: Exactly. Look, I’m a gearhead. I love robots and spaceships and all the hardware, and science fiction has always had all the great ideas for what we hypothetically could invent. It was always about human potential. The sci-fi of the ’50s and ’60s was extremely dystopian. It was really about all the ways that our technology and our science could kill us. It was very hopeful in the ’30s. We’re going to expand to the stars and meet interesting other races and all sorts of things, invent humanoid robots and do all kinds of cool stuff. Then World War II came along, and in the wake of the Cold War and nuclear weapons, science fiction got very, very dark, probably right up until Star Wars. Lucas threw out the dystopian playbook. He turned space opera into mythic storytelling in the John W. Campbell mold. And this science fiction made a lot of money. But it stopped being the conscience that it used to be. Now, I think it’s sort of found a balance between [conscience and] fun, and Avatar, I think, is right in the middle. It certainly has the aspirational fantasy—I want to be there, I want to do that, I want to ride creatures and all that cool stuff—but it’s got the moral parable as well.

Hannah: Do you think there was more of an appetite for technological optimism in science fiction literature, with authors like Arthur C. Clarke? Actually, Sigourney, I heard that Arthur C. Clarke came to one of your parents’ parties to show them something in an issue of Playboy that you later snuck out of his bag.

Sigourney: That’s true. My first issue of Playboy. My father loved space, we got a telescope and we looked at the stars and talked about them. We had a very positive idea in America, going to space. It was not about space wars. It was about exploration of space. I think the first book my mother ever read to us was Robinson Crusoe, which is not really the thing to read to children under six. And it was an adventure, and it was this man on an island. He could have been on a planet, figuring out how things worked. I had so many nightmares about that book when I was small. But I haven’t read many [science fiction] authors. I’ve read Octavia Butler, because she’s one of our daughter’s favorites.

James: I grew up on a steady diet of science fiction. It’s literally all I read while I was in high school. I had a one-hour bus ride to and from school, so I was on a bus for two hours a day. And with all of my in class reading behind my math texts, I pretty much was knocking out a 200-page pulp scifi book a day. And you were steeped in proper literature. You even took your stage name from a character in Gatsby, I think, right?

Sigourney: It’s true. I almost got into a fistfight with someone in college, arguing between Hemingway and Fitzgerald. Maybe there was a competition between them but, really, their writing is so different I don’t know why that even was a thing. But the written word seemed, and it still does to me, incredibly powerful and an opener of so many doors.

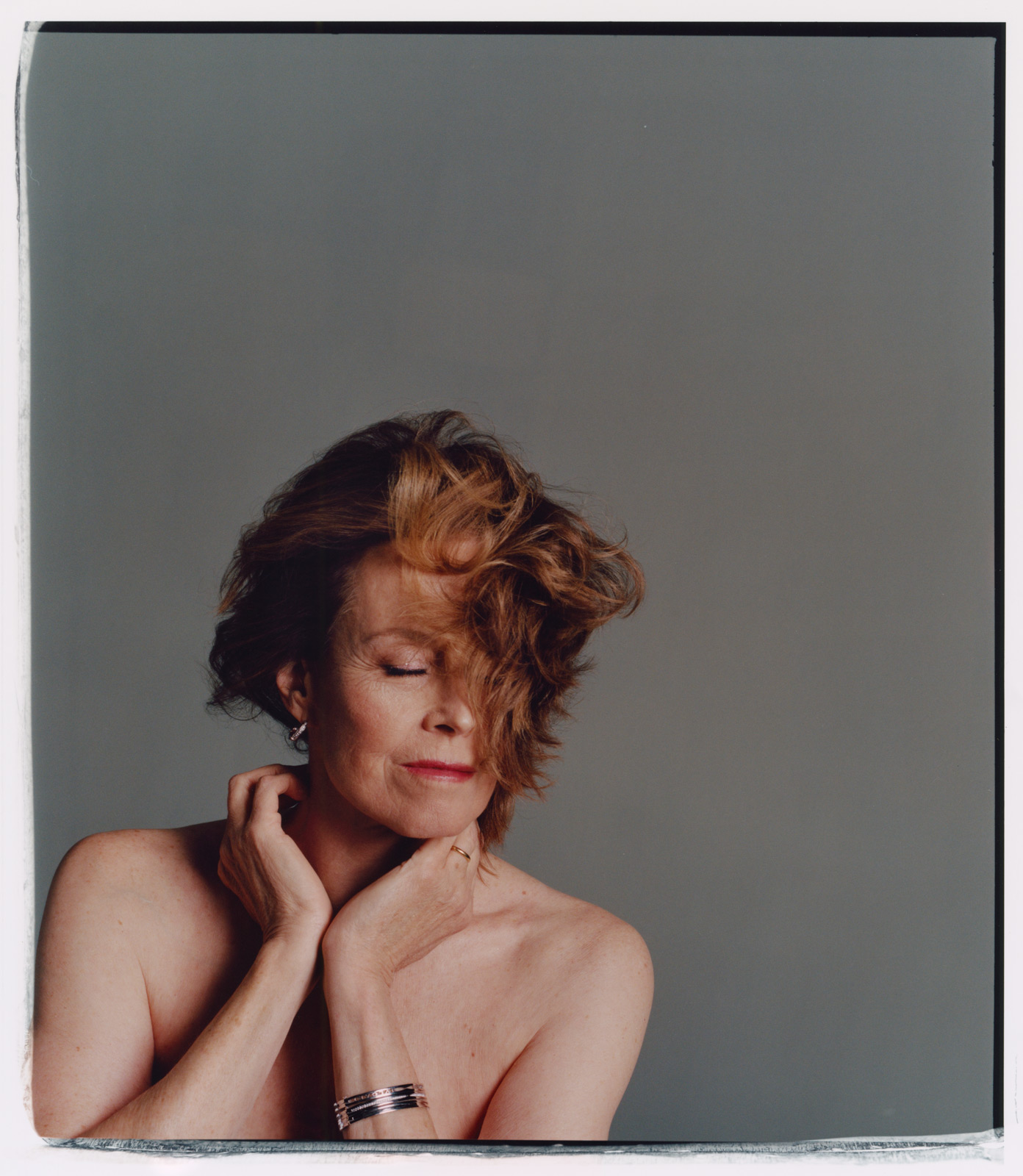

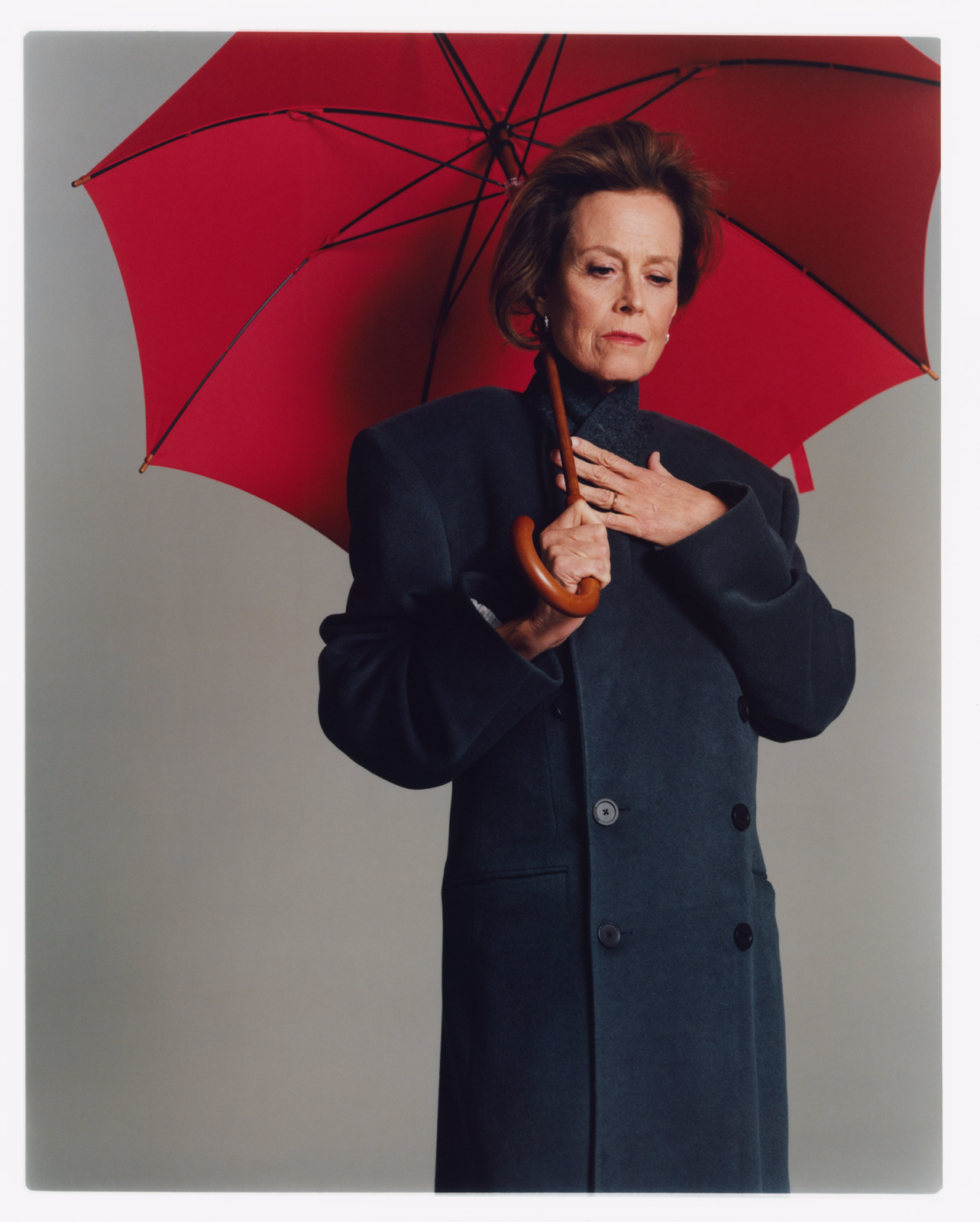

Hair Peter Gray for BOB Styling at Home Agency. Make-up Brigitte Reiss-Anderson at A-Frame Agency. Set Design Todd Wiggins at MHS Artists. Photo Assistants Mitchell Stafford, Xavier Muñiz, Ivory Serra. 4×5 Operator Kirk Edwards. Stylist Assistant James Kelley. Tailor Olga Dudnik. Set Design Assistants Montana Pugh, Arlington Garrett, Kylie Baker. Production Ms4 Production. Casting Tom Macklin. Handprinting Natalie Hail.