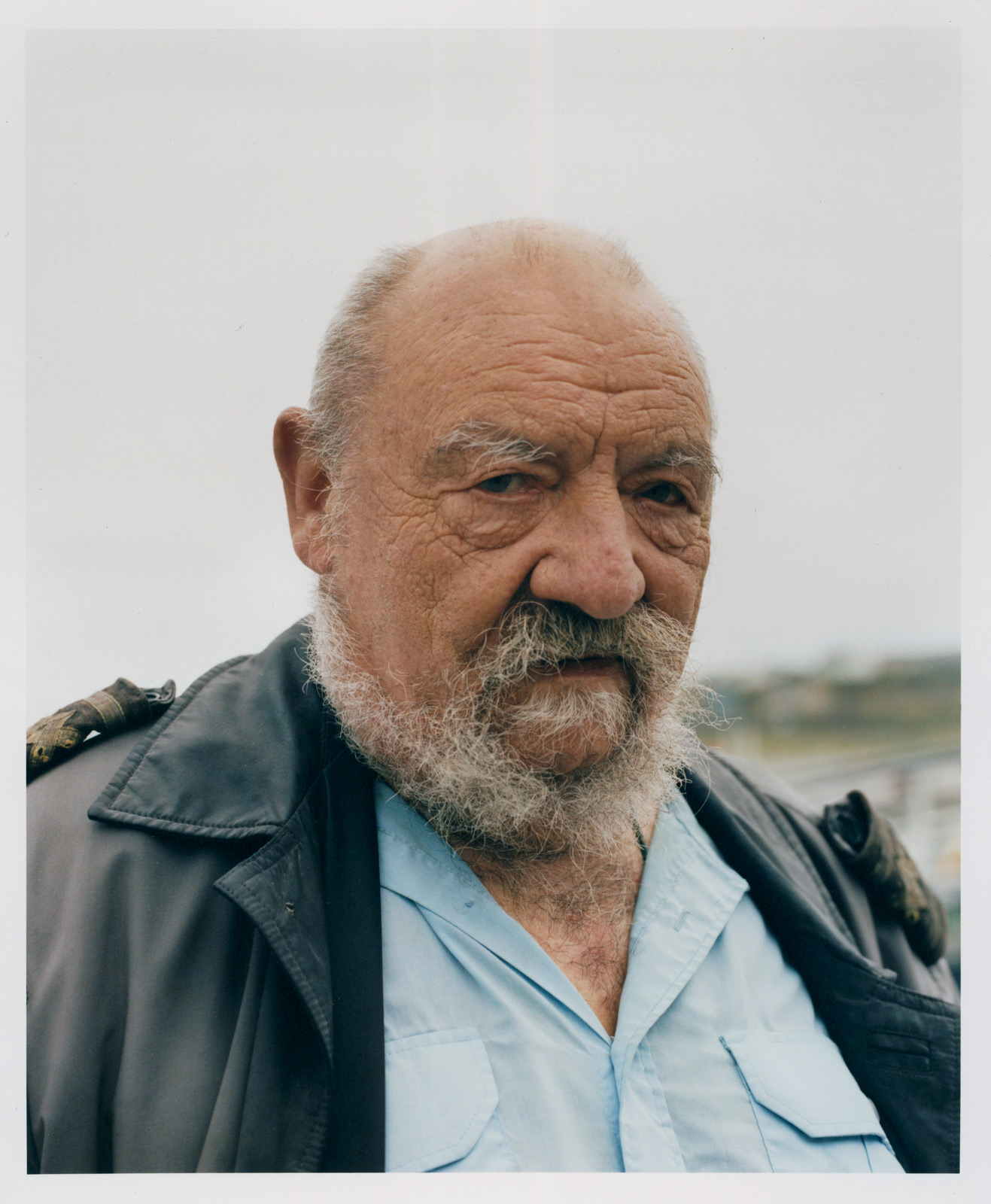

The New York-based artist captures intimacy in portraits and landscapes alike

There is an earnestness to Chad Unger, the kind of earnestness that feels rare in the world of art where ego is often an unsaid credential of entry. The now New York-based photographer could easily slump into the world of the Lower East Side art bro elite—he’s got the mustache, the natural athleticism hidden under loose-fitting tees, the charming smile, and the artistic talent that, together, undoubtedly would allow him to get away with being an asshole. (If I was gifted with that combo, I would be.) But Unger is warm and kind, qualities which carry over to his work.

It’s difficult to categorize him in the same ways we often do those we don’t know intimately. He is an artist and an athlete, and he is gay and deaf. Identity is central to art—the complexities that make up Unger are part of what makes his images so unique. That, along with a modesty that translates into eagerness to learn and evolve.

Unger grew up in Maryland where he was completely immersed in the deaf community. He was raised in an all-deaf family and attended an all-deaf school. In high school, he submerged himself into the world of Tumblr, where his first experiments in photography took place. Snowboarding began to dominate his life when he moved to Colorado for college, but after transfering to a school in Utah, where he took a photography course, his work took on new life. While he was working as a trimmer at a weed farm, Unger’s work really evolved into the narrative-driven photos that occupy his current portfolio.

His portraits and landscapes are equally intimate, balancing soft, filmic tones with striking subjects. Unger joined me over Zoom, along with his interpreter, to discuss the evolution of his work, his philosophies of practice, and his recent move to New York.

Megan Hullander: Do you feel like people over-credit the importance of your deafness in regards to the quality of your work, or do you think it’s something that is really defining of your perspective?

Chad Unger: Originally, I really did think that that was true. After a while, I started to change my mind. I do think that my work is recognized first. They can’t see [my work] and be like, ‘A deaf person took that photo.’ They actually saw my work as the work it was.

Megan: Are there any experiences of shooting you can pinpoint that changed your perspective on how you approach photography?

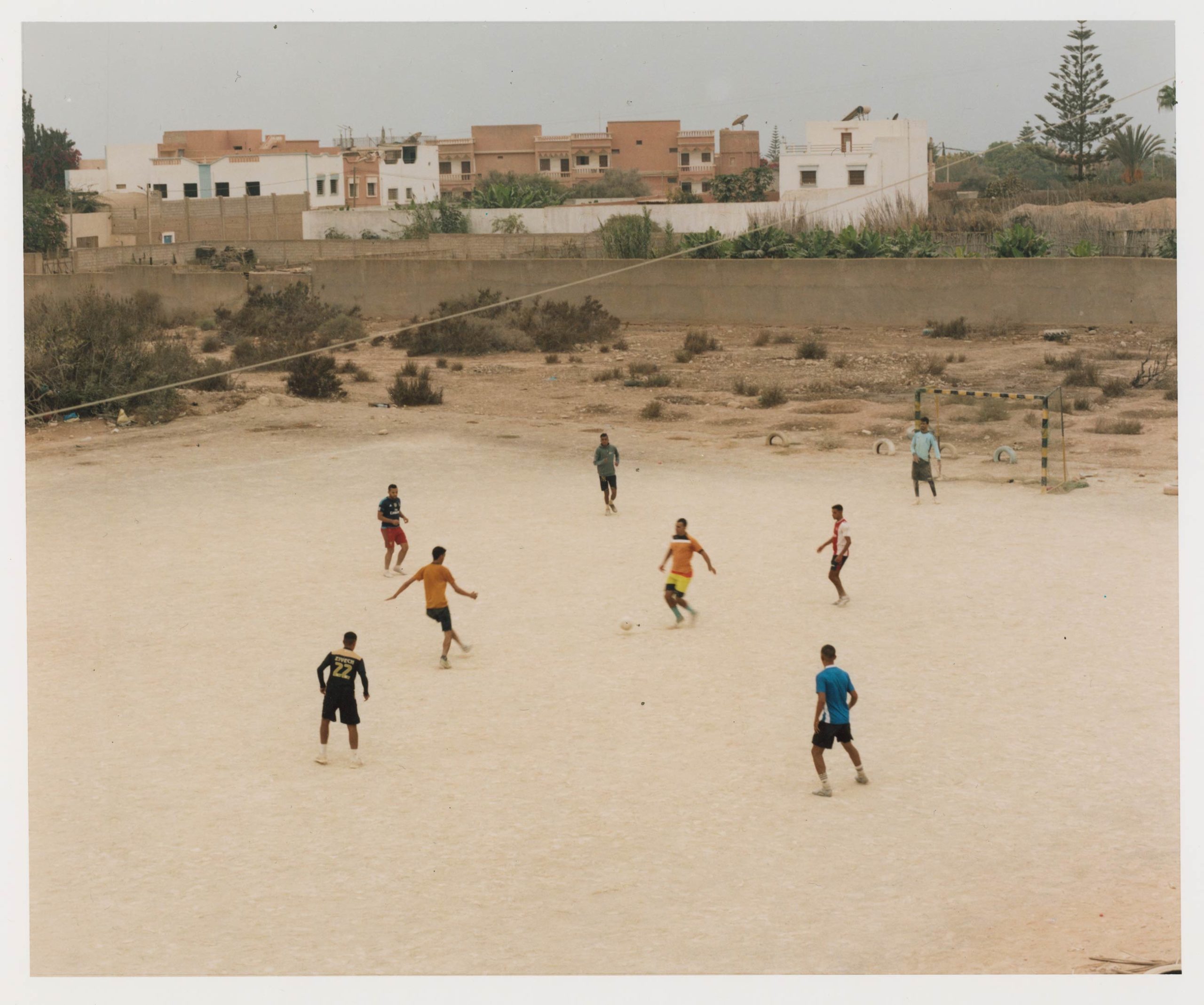

Chad: I went to Morocco by myself for travel last fall. For a long time, I was nervous about shooting people, and it was during that trip that I would just do it. I would just always point at my camera, and then give them a thumbs up, and then I would continue shooting people. I feel like I was able to use some cues and gestures with people to help them understand what I was trying to tell them—like whether I was asking them to move or change their face. After that trip, I started to think, ‘Maybe I really could start shooting people without saying anything.’

Megan: As both an athlete and an artist, have you found that—outside of just directly shooting other snowboarders—there’s been any sort of intersection in how you approach those identities?

Chad: I tried to bring them together. But I just couldn’t get what I wanted from it. I do think people can, and it’s possible to create art within snowboarding. But I realized that I couldn’t really quite do what I wanted with snowboarding—that it wasn’t for me. You can make art snowboarding. After three years of doing that, I realized it wasn’t something that I could continue doing. And so I felt like, you know, New York—it’s the Big Apple. So I’m here.

Megan: And New York is a very different environment from where you grew up. Have you seen a reflection of that in your work?

Chad: Oh, it’s definitely influenced it, for sure. I have some opportunities to work with photographers who have worked for years and years and years. I realized how much I have to learn, and that that was okay—that I have to learn patience and I have to be okay with that pace of learning. It’s really great to meet other people and actually tell them about my experience. When I was in Maryland or Salt Lake, I couldn’t really talk about my work—I just didn’t feel like I had those opportunities. But people here seem to understand that, and that’s been really nice.

Megan: And how do you feel like your communities influence your work?

Chad: I haven’t lived in New York City for very long. So I don’t have a lot going on that way. But I do feel like I have some ideas that have changed my identity or influenced my identity, whether it’s the gay community or the deaf community, which I belong to both.

Megan: Do you feel like you’ve had any sort of personal growth since you started photography? Has it helped you understand yourself?

Chad: Without a doubt. Not necessarily, like, work-based, but based in who I am—learning that I do feel like that will change over time, and I can improve, and when I improve on work, then it improves everything else. The work itself improves, and then I as a human improve. I’m not the most patient person, so I know that will take work. I know that it takes time, and it’s not gonna happen overnight. I’m in it for the long haul.