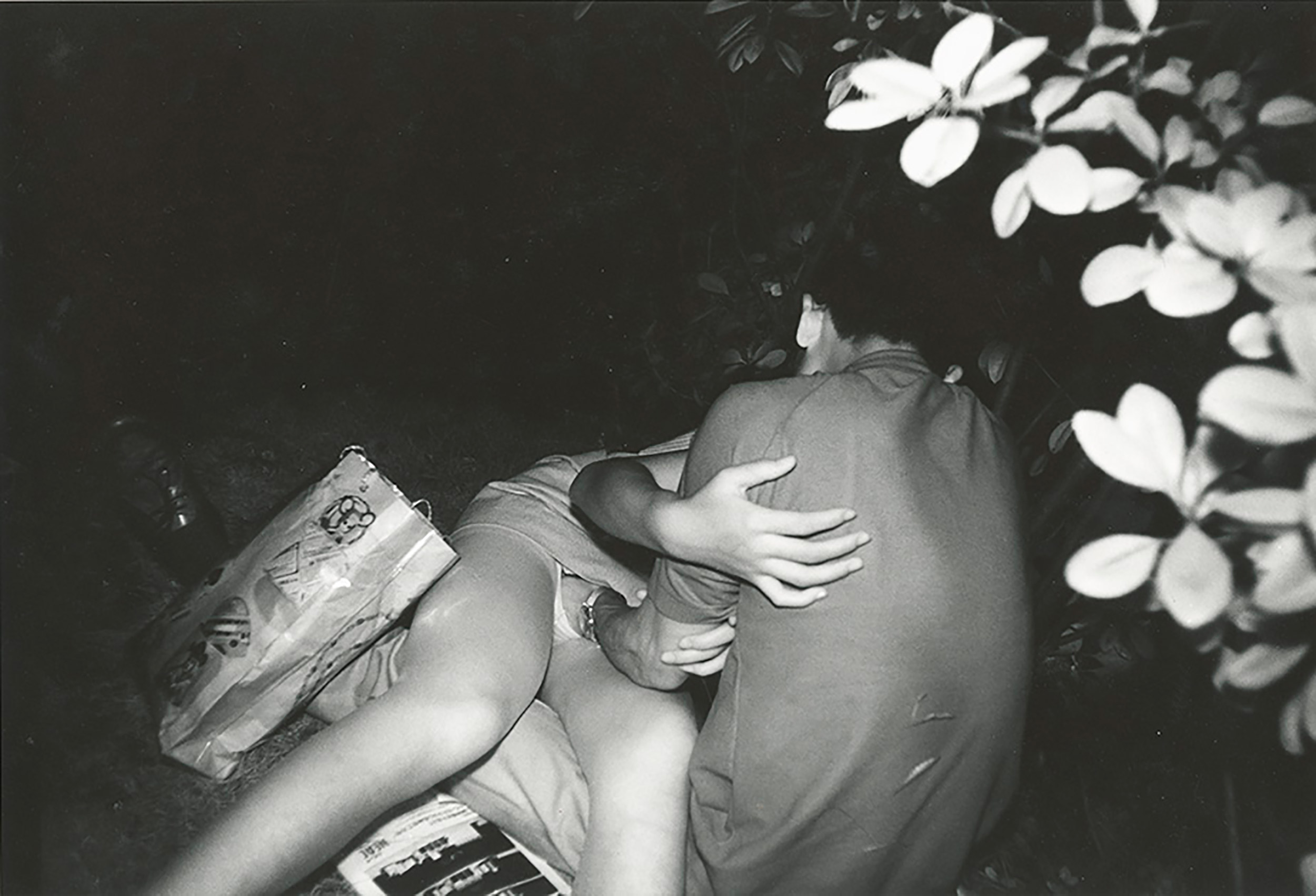

The photographer took thrilling, transgressive photos of young couples—and their onlookers—in 1970s Tokyo.

Under the cover of darkness, Japanese photographer Kohei Yoshiyuki crept through Tokyo’s Shinjuku, Yoyogi, and Aoyama Parks during the 1970s, in search of an illicit world known to a select few. Moving like a hunter on the prowl, Yoshiyuki used infrared film and flash to capture public displays of sex between heterosexual and homosexual couples—and, perhaps more shockingly, the voyeurs who gathered to watch.

“One day I stumbled on the scene—and [an] incredible scene [Laughs]. That was when I was still an amateur,” Yoshiyuki tells Nobouyoshi Araki in a conversation titled “Tiptoeing into the Darkness…With Love,” featured in the new book Kohei Yoshiyuki: The Park.

“I was shocked. They were actually fucking,” Yoshiyuki says. “When I saw them I knew this was something I had to photograph.”

From 1971 through 1973, Yoshiyuki made this body of work and then returned again in 1979 to complete the series of ethereal, otherworldly scenes. That same year, he exhibited the life-sized prints in Komai Gallery in Tokyo. “I turned out all the lights in the space and gave each visitor a flashlight,” Yoshiyuki tells Araki. “That way I was reconstructing the original settings.”

By transforming viewers into participants, Yoshiyuki layered transgression upon transgression to thrilling effect, his photographs just as thrilling now as they were then. “I realized how much I was implicated in what was going on by just looking,” says Vince Aletti, who wrote an essay for the book. “By being part of seeing everything through his eyes, there’s no way you can’t be pulled into that and become another voyeur or understand the drive and the mania of it.”

Yoshiyuki’s obsessiveness mirrors that of the subjects of his work and the risks they are willing to take to satisfy their desires, whether voyeur or exhibitionist. “It wasn’t one or two guys watching from a distance; there are often for our five and they were right in there,” Aletti says.

“There’s no way that the couple that was having sex didn’t know they were being watched and sometimes touched. The idea that this became an orgiastic situation but with almost everyone fully clothed is part of the bizarre nature of the whole thing. It seems a little insane—so daring and beyond what I imagined was going on in Japan, which I always thought of as an uptight, prim society.”

Indeed, there is a curious sense of formality in the fact that despite being en flagrante delicto, the couples are almost always fully dressed. Their sense of abandon is carefully moderated by the awareness that they are surrounded by strange men crouching and crawling on the ground, often daring to insert a hand where it does not belong.

“[The voyeurs] are almost hopeless,” says gallerist Yossi Milo, who first learned of Yoshiyuki’s work while reading a brief mention in Martin Parr’s The Photobook: A History. “It is very animalistic behavior, especially when you see four or five guys on their knees, watching like lions.”

Yoshiyuki was one of those cats stalking his prey, searching for the forbidden pleasures of the flesh and translating them into vivid tableaus of carnal pleasure and deep longing for intimacy.

“When Yoshikyuki was taking these pictures, Japan was on the rise. Real estate was extremely expensive at that time, especially for young people,” Milo explains. “A lot of young professionals had to live with their family. They couldn’t take someone home; they had to go to public places for privacy. If you look at the pictures very carefully, you will see beautifully dressed men and women who just left work; they have tennis rackets and Burberry umbrellas. They are not going out all of a sudden in the middle of the night.”

Yoshikyuki developed an eye for couples on the make, telling Araki, “You can always spot them because they walk fast.” He honed his skills with the knowledge that photographing people having sex in public isn’t illegal. He explains, “As long as you don’t say anything. If you keep quiet, take your photos and run, it’s okay.”

By transcending the binaries of privacy and surveillance, invisibility and visibility, prudishness and prurience, Yoshiyuki has produced masterful and mysterious images of sexual encounters that are neither graphic nor lascivious, yet filled with lust, desire, and compulsion.

Because of the photographer’s infrared flash, it’s easy to forget that everyone was groping blindly in the dark. There is no ambient light from street lamps or light pollution to brighten the night sky. Yoshiyuki, like the voyeurs, benefited from this. By moving in closely, his physical proximity adds to the tension and thrill, the danger of being caught and exposed on both sides of the camera.

Like many of his contemporaries of the late 1960s Provoke movement, Yoshiyuki’s work would go one to inspire a new generation of artists to use the camera to instigate, incite, and challenge the way we see and think not only about the world around us but the medium of photography itself.

“When this work came out, it was quite revolutionary,” Milo says, noting that a limited edition of The Park includes a facsimile reproduction of the groundbreaking 1980 Japanese publication Document Koen [Document Park]. “They sold over 100,000 copies of the magazine. People wrote letters to the editor that they wanted more because it was such a sensational, frightening discovery.”

Then Milo reveals another layer to the mystery surrounding this work: “Yoshiyuki was not his real name. It is a studio name he gave himself. I don’t know his first name or last name, but it has been ‘Yoshiyuki’ since the 1970s because he was very concerned about this body of work.”

By maintaining the anonymity of his subjects and himself, Yoshiyuki has blessed us with a stunning portrait of human sexuality liberated from the strictures of culture and civilization. In returning to the wild space of the public park, Yoshiyuki affirms our primal desires that continue to exist despite society’s relentless crusade to domesticate them.

At the same time, his need to document these desires speaks to our present age, when the invasion of privacy can literally jeopardize lives. “We are in an age where images are flying so fast,” Milo observes. “Looking at such an important document reminds us of many of these things happened 40 years ago.”