With babushka scarves and cabbage-inspired coats, Eastern Europe's next generation trades 90s nostalgia for an avant-garde future.

In his dark and moody studio in Kiev, Ukrainian designer Artem Klimchuk motions to a rack full of babushka scarves—the same kind the elderly women directly outside (and the likes of A$AP Rocky and Marc Jacobs, lately) wear around their heads, knotted at the neck and styled with long dresses. The designer, though, has rendered them in neon fishnet fabrics with contrasting piping and decadent, sparkly embroidery.

Klimchuk is not the only label garnering hype for its unconventional, non-commercial take on fashion in Eastern Europe. Take Ksenia and Anton Schnaider of KSENIASCHNAIDER. The design duo’s latest must-have? A pair of jeans with one massive wide leg and another skinny, fitted leg.

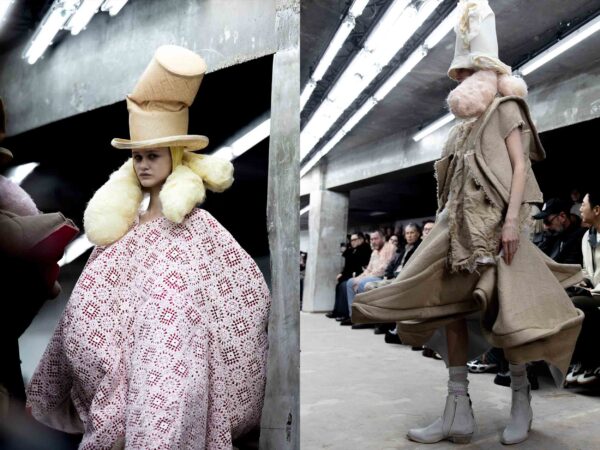

There is such a market for this kind of fashion in Ukraine that Kiev recently launched the biggest emerging designer contest in all of Eastern Europe. On a breezy night earlier this month, Ukrainian Fashion Week hosted its second edition of the International Young Designers Contest, inside the city’s Mystetskyi Arsenal National Art and Culture Museum Complex. Designers were handpicked from Czech Republic, Georgia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Ukraine to present five looks each in a runway show. The winner— Anastasia Padalka, whose collection was composed of crafty-looking transparent fabrics and punk iconography with embroidered face-coverings—received a $10,000 grant and a course in one of the programs at IED-Istituto Europeo di Design in Italy.

Watching the competition runway show, I couldn’t help but think about the impact of Eastern European fashion globally. In 2014, Vetements debuted in Paris as a mysterious collective who made awkwardly spliced jeans, oversized hoodies printed with slogans, and leather jackets with sleeves that extended far beyond the wearer’s arms. The lead designer was eventually revealed as Georgian-born Demna Gvasalia, who in 2015 was named creative director of Balenciaga. Gvasalia’s rise is largely thanks to the Soviet Russia-born stylist behind Vetements’ shows, Lotta Volkova, who mainstreamed “bad taste” by mashing up the aesthetic codes of Eastern and Western subcultures. Volkova has also worked with Gosha Rubchinskiy, the Russian designer whose brand has referenced Ronald Reagan’s Cold War-era ‘Evil Empire speech,’ George Orwell’s fictional dystopias, and the creativity of post-Soviet youth.

“‘I believe that art is one of the most effective tools of changing attitudes of humanity, in regards to many issues,’ [Georgian designer Levani] Shvelidze says.”

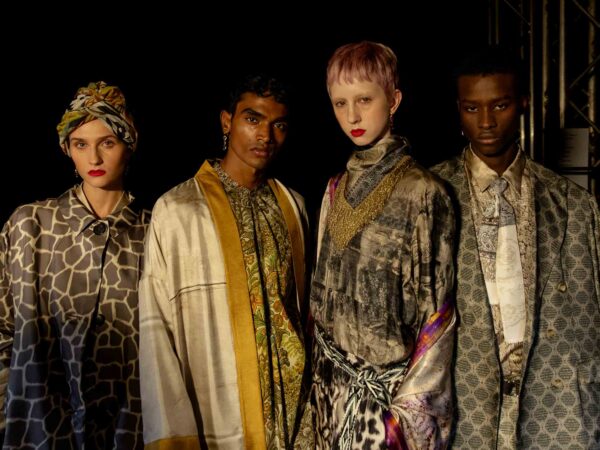

These designers felt intrinsically new at the time—like they brought something to the fashion world that was missing. But almost 30 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the voracious cultural exchange that followed, the next generation of creative youth in Eastern Europe is less enchanted by a singular post-Soviet aesthetic centering appropriated Western pop culture. This generation is instead carving out a post-post-Soviet identity focused on traditional craft, art collaborations, and statements about the unique political situations in their home countries.

At Kiev’s International Young Designers Contest, Estonian designer Katrin Aasmaa developed a menswear collection featuring sequined tweed short suits and dapper tailored coats inspired by her great aunt’s cabbage field. One of the male models also stomped down the catwalk wearing thigh-high yellow wellies. “I cut a cabbage in half, and copied all the lines within the patterns of the garment,” she explained after the show. Karl-Christoph Rebane, also from Estonia, sought to challenge his home country’s idea of masculinity, showing a debut collection that featured exaggerated shoulders, rainbow-colored sleeves, and black belts resembling penises.

“We push boys down for being too flamboyant, we create a grey mass of walking flesh, we celebrate with a show of toxic masculinity and [military] tanks followed by emotionless boys in army suits and joyless confetti,” Rebane commented. “I want to be an artist living from selling my own creations. This collection is about my experience with the Estonia army and how I tried to protest it, but in the midst of that, I found a way out of it. It’s a spectacle of emotions.” The title of his collection—‘Am I joke to you?’—is the question he posed to his country. In Estonia, a country once considered relatively progressive, the far right has recently gained power, and the government currently does not recognize same-sex marriages.

” This generation is carving out a post-post-Soviet identity focused on traditional craft, art collaborations, and statements about the unique political situations in their home countries.”

Latvian designer Laima Jurca used prints inspired by Soviet-era tablecloths in wax cloth—colorful fruits, canned foods, florals, and everyday objects—but rendered them in avant-garde, architectural shapes that covered models’ entire bodies. Her pieces were closer to walking art installations than everyday attire. Additionally, Georgian designer Levani Shvelidze’s collection was inspired by the birth of new creatures from Dracula and Morticia. “I believe that art is one of the most effective tools of changing attitudes of humanity, in regards to many issues,” Shvelidze says of the collection. Romanian designer Alexandra Iuliana Iancu showed stunning outré coats that resembled vibrant Cubist paintings. “I’m trying to encourage people to select clothes with artistic value instead of ready-to-wear,” she mused. Unsurprisingly, many of these emerging designers produce limited quantities of their unusual creations. “I just produce the quantities that I can definitely sell,” says Czech native Tereza Rosalie Kladošová of her vibrant merino wool coats. “In this way, I contribute to the sustainability of the fashion industry.”

According to Victoria Kharchenko, the project manager of the contest, the goal of showcasing non-commercial designers was a shared one, driven by the desire to communicate the multi-faceted nature of Eastern Europe’s post-Soviet identity as well as its lingering political tensions. “For a long time, we didn’t have this opportunity to express ourselves,” Kharchenko says, referring to the current political climate in Ukraine, which still has an extremely tense relationship with its neighboring Russia following the Russian occupation of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula in 2014—and Ukraine’s subsequent increasing commitment to NATO and the European Union. These young designers were not impacted by the influx of Western consumer culture that characterized Gvasalia’s formative years, but they are living through their own political tensions, and figuring out a new sense of identity through art.

There’s a lack of clear consensus on this identity and it’s not likely to be resolved soon. Ukraine’s new president is a former comedian whose only political experience is playing a president on TV, and who takes office amidst a struggling economy as well as an escalating war. The former Soviet nation of Moldova, which also took part in the design competition, is dealing with similar political unrest—including a coup attempt by its pro-Russia president, who was then pushed out of office by a Moldovan court (a snap election has been called for in September). Democracy is under siege in Romania and officially dead in Hungary.

With the memories and stories of the older generation’s lack of freedom hanging over their heads, young designers in Eastern Europe are refusing to be characterized by an all-encompassing post-Soviet aesthetic—but they are all bold, unafraid, and unapologetically expressive.