The art made by Guantanamo Bay detainees and the photographs of Edmund Clarke, both on display in New York City this spring, offers new perspectives to the drab palette of indefinite war—and the endless reach of American hegemony.

There are few things that typify the War on Terror more than Guantanamo Bay detention camp. It is the site of some of the United States’ most flagrant ongoing human rights abuses from the use of torture as an “enhanced interrogation tool” to indefinite detainment and the absolute suspension of the right to trial. To date, only 10 of the 41 men currently incarcerated have been charged or convicted. One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter, or so the adage goes. The politicized naming (or not) of domestic terrorists, from animal liberation activists to white supremacists to school shooters to serial bombers, makes manifest the dangers of trying to play terrorist-or-not—and where would the United States rank on this list? Yet it is undeniable that the mistreatment of these terrorism suspects has become a valuable recruitment tool for groups such as al-Qaeda, ISIS, and their myriad sympathizers. The iconic uniform worn by “non-compliant” detainees—those orange jumpsuits, those black hoods—has in particular become a powerful sartorial synecdoche for protesters and ISIS alike. Barbed wire, mesh fences, U.S. soldiers in camo and brown men on their knees wearing orange amongst endless beige: the drab palette of a war we no longer notice.

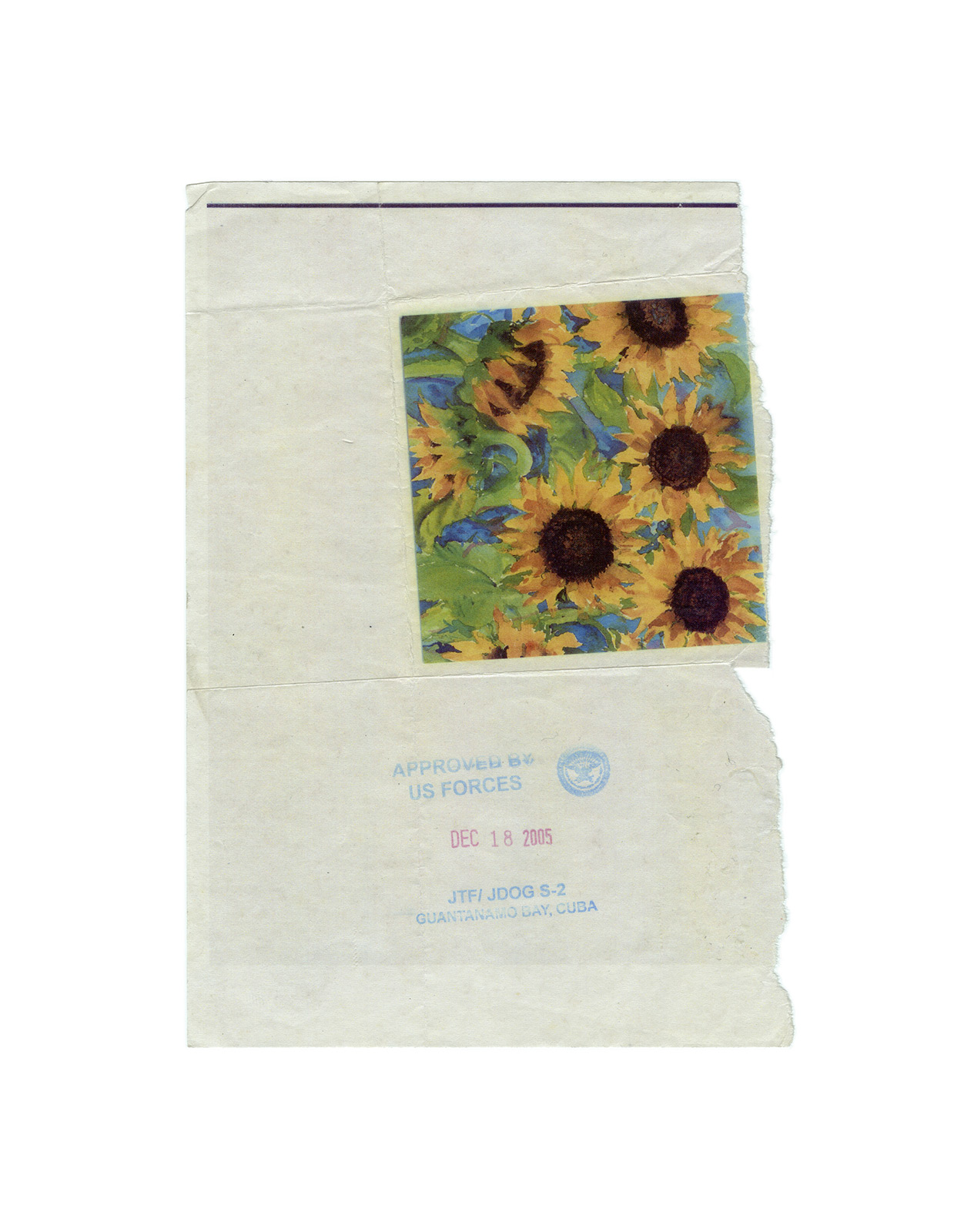

Two shows recently on view in New York provided a more nuanced picture. The first, Ode to the Sea, opened at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in early October and featured art from eight Guantanamo detainees or “forever prisoners” past and present. As the title suggests, seascapes predominated the selection, often featuring boats or bounded by mountains, shorelines, or a pedestrian corniche. Apart from a rendition of three-year old Aylan Kurdi facedown on the beach, an image which came to encapsulate the so-called migrant crisis, there are notably few people in these images. Speaking to Art Newspaper, co-curator Paige Laino noted that detainees would display their finished works in their cells for the enjoyment of all and, as such, the absence of figuration is likely out of respect to Islam’s interdiction against depicting the human body. All the work was made in the prison’s popular art classes, introduced by the Obama administration in 2009, which detainees were allowed to gift to lawyers or their families following a rigorous security screening. “The art program provides intellectual stimulation for the detainees and allows them to express their creativity,” a press caption released by the Department of Defense said at the time. The sails of one intricate ship sculpture (made from cardboard, old t-shirts and the plastic packaging of shaving razors) even bore the “Approved by U.S. Forces” stamp that evinced the work’s stringent vetting process.

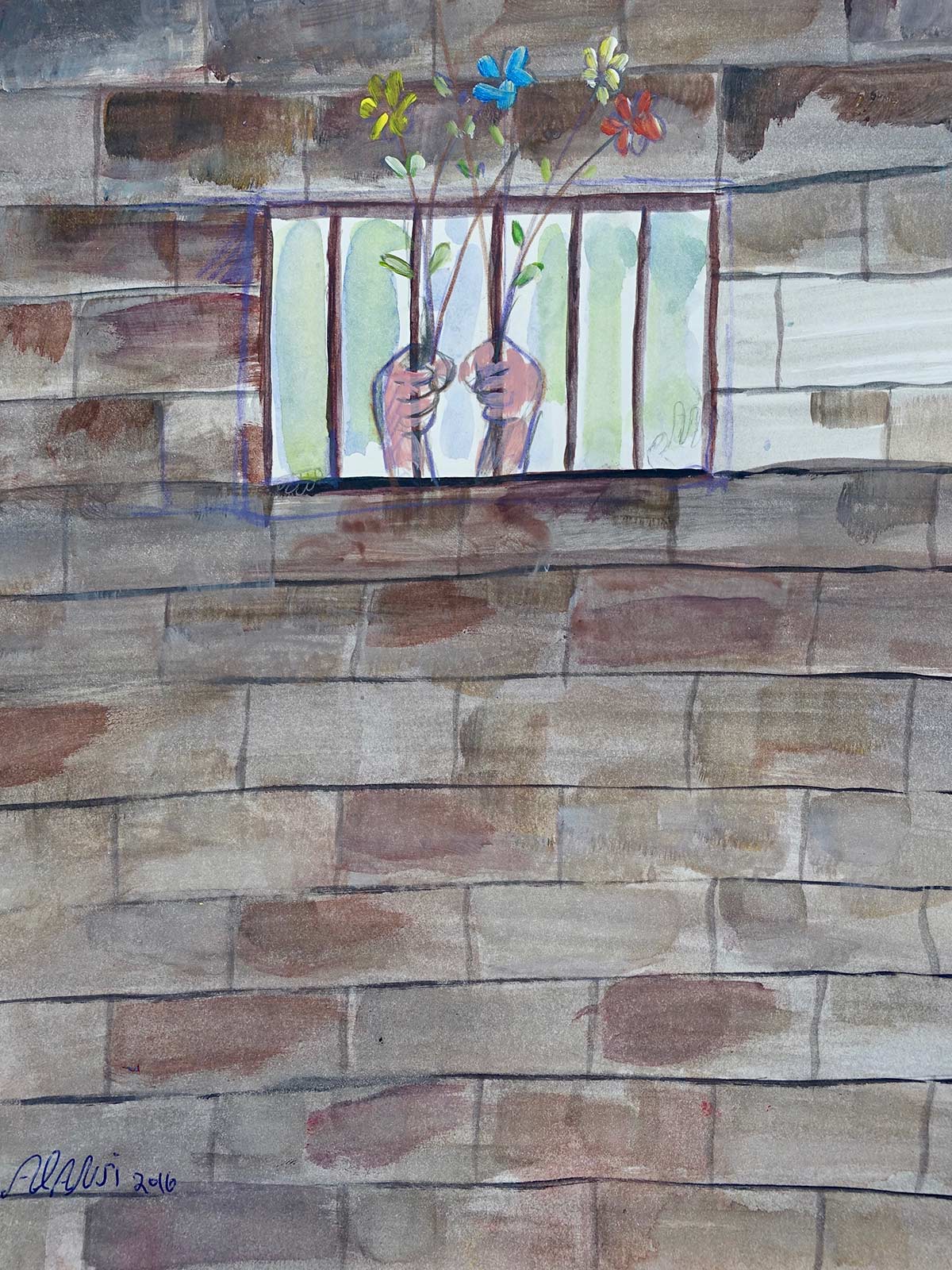

The paintings seem to have a thin, almost parched quality to them, as if all the water in the world couldn’t possibly be enough. At times, the symbolism was especially, if overly, portent: here’s the ill-fated Titanic steaming its way towards its watery grave, or, a pair of disembodied hands clutching flowers around the bars of a high cell window, the Statue of Liberty. (In the same interview, Laino added that the instruction was very much of the learn-by-reproducing variety and that many paintings were based on images from National Geographic, one of the few publications that inmates had ready access to.) Other paintings featured palm trees, minarets or flat-topped houses characteristic of much more arid climes that seemed to telegraph a longing for a home their makers may never see again. Anyone expecting any insights into daily life at Guantanamo Bay or a strong political message would have been disappointed. The 36 paintings, drawings, and sculptures were remarkable only in their pleasant banality. They were utterly non-threatening, and this was precisely the point.

Documentation of the show, which closed in January, suggests it was a fairly nondescript affair with simply framed paintings hung under the glare of institutional tube lights in a worn, carpeted holiday. Some 9/11 families objected, but the exhibition was generally enthusiastically received and widely reviewed. Within six weeks, the Department of Defense announced a new policy. They were concerned that these potential “terrorists”—many whose criminality is suspect in the first place—might profit off the sales of their work, that they might be used to fund further attacks. Effective immediately, they suspended all transfers of artwork out of Guantanamo pending a policy review, and moreover, declared that all art produced at Guantanamo would was now “property of the United States.” Artwork of detainees who had left the base would be incinerated, a decision that was quickly walked back in the face of the furor that followed. Instead of being destroyed, it would now be archived.

All in all, the Pentagon’s knee-jerk response proved to be a masterclass in the Streisand effect, creating a further PR nightmare for an institution already beset by them, and further depleting what little public goodwill Guantanamo Bay might have had left. Yet as the takes unspooled and the news cycle moved on, some important questions remain. It seems patently hypocritical that bonafide war criminals like George W. Bush, under whose aegis Gitmo opened, have weaponized art to rehabilitate their own images while the detainees—some of whom, again, have yet to be formally charged with a crime—are denied the same humanizing opportunity. The example of Anthony Papa and Mike Kelley suggests that there might indeed be liberation in art beyond the spiritual or the material. Who should own the works, the state or the artists that the state has extrajudicially detained? What about prison narratives on the dignity of art? Despite the recent flurry of performative mea culpas, art’s inextricability from capital has rendered any possible potential of creating material political change impotent. Yet, in banning these works, is the government implicitly reifying the power of art and implying that it actually, well, does something?

“The sea is history,” Derek Walcott wrote. It’s that grey vault that locks up all the monuments, battles, martyrs, all the tribal memory of those denied a history. And I wondered about all that watery symbolism in the John Jay show, all the more remarkable when considering waterboarding’s transmutation of water into a tool of torture. I learnt that the Guantánamo province, otherwise immortalized in the beloved Cuban folk song Guantanamera, takes its name from the indigenous Taíno language. The word refers to a place between two rivers, or rather more poetically, “the existence of the sea.” As nomenclature goes, it’s worth noting here just what a misnomer the phrase “detention camp,” and by extension, “detainees,” is in its intimation of impermanence, a temporary hold, being not-indefinite. And yes, the facility is part of an American naval base, but its visual vocabulary is one of fencing and enclosure, and so many shades of greige. I hadn’t even realized the prison was on the water. Could detainees even see the sea?

A moving essay by former detainee Mansoor Adayfi in the exhibition catalogue provides some elucidation. Even in those initial months where they did not know which direction to pray in, let alone which country they were in, they were always infinitely aware of the sea, just a few hundred feet away but always excruciatingly out of sight. The Afghans had never seen the sea before. The Arabs tried to explain with words and pictures, but actually gazing upon the water proved near impossible. Glimpses could be had from under tarps, or some cell windows, but looking out at the sea came at the risk of punishment by guards. It was only during a 2014 hurricane when the tarps came down for a few days that detainees were able to look out onto the bay. Shortly thereafter, it began to feature heavily in their art and poems. “The sea means freedom no one can control or own, freedom for everyone,” he writes. “Each of us found a way to escape to the sea.”

I looked up the camp on Google Maps. The border between the United States and Cuba looks like a piece of dog-eared paper, the skeuomorphic kind that will be remembered as a digital icon long after the last trees have been cut down. Fittingly, for a site inextricable from the multibillion-dollar war-prison industrial complex pipeline, the camp is listed as a business. The new mandate further complicates this in its implicit characterizing of art as a product of another lucrative industry, prison labour. Its accompanying interior shot shows a study in utilitarian ecru of cell. Its hours, according to Google, are 24/7. Opened in 2002, George W. Bush would whittle the population down to 242 from over 700 over the next eight years. Obama promised to close it but managed only to reduce detainee numbers down to 41, only a quarter of whom, again, have been charged. Following his campaign promise to “load it up with some bad dudes,” Trump signed an executive order in January to keep it open—and here’s that word again—indefinitely. Has there ever been an adverb more thoroughly maligned?

These new policies in which a prisoner is released but their art remains incarcerated are fascinating in the way in which they invert the logic of the art world, and the globalized neoliberal economy more broadly, which assumes the free passage of products not people. And it’s worth reiterating: art is not held hostage by the forces of market so much as being its willing, even enthusiastic bedfellow. Moreover, it functions as a primary conduit of money into (in the form of looted antiquities) and out of (as elites scramble to safely store their wealth in Dubai, Singapore, Switzerland or other offshore tax havens of their ilk) the same countries that the War on Terror has ravaged. More insidious however is the fact that release does not necessarily mean freedom for these prisoners but rather often takes the form of being transferred to prisons in other friendly, mostly Arabian Gulf, countries. This is not always a repatriation but rather an exercise in diplomacy. It can be assumed that compensation for taking on this burden materializes in another ways, whether in the form of arms and various trade deals or intelligence aid. In the case of Qatar, it was the release of an American officer. Still, the often shared language and culture is seen as a boon for the rehabilitation of these mostly “low-value detainees,” a term that indicates they were held without trial for up to 14 years before being cleared for transfer. Optics matter as the War on Terror nears its second decade and these transfers can be understood as a human NIMBY-fication, not unlike the way in which poorer neighborhoods bear a disproportionate burden of hazardous waste sites and homeless shelters, just extrapolated on a global scale. New suspects might not be sent to Guantanamo anymore, but are instead interrogated on ships (as with the parallel “floating Guantanamos of the War on Drugs”) or held in other sites outside of the legal—but not military—reach of US systems.

We might understand this outsourcing of detention in terms of what philosopher Giles Deleuze has characterized as a “society of control.” It builds on Michel Foucault’s concept of a disciplinary society to describe a more contemporary present in which technology allows states to carve out new forms of control which are so sophisticated that they render older forms irrelevant. The radical expansion of U.S. hegemony is one such example of this, as is the IDF’s strategies that weaponize urban deterritorialization. Just as incarceration does not always feature walls or fences—consider how Flint, Michigan hasn’t had clean water since April 2014—you no longer need to be within the barbed wire and tarps of Guantanamo to remain very firmly under U.S. control.

A second show of Guantanamo-related work from Edmund Clark at NYC’s Institute for Contemporary Photography visualizes the long shadow of U.S. control. Again, the familiar stamp “Approved by U.S. forces” appears on one work that documented letters of support sent to a detainee. Even outside the realm of soft power, U.S. dominion has long extended beyond the physical with a reach that is not an elongated arm so much as a coming face to face with the barrel of a Kentucky rifle. Yet the policing of support on display here suggests that the U.S. seeks to further extend its jurisdiction to the affective realm. In this domain, the line between sympathy and solidarity is closely monitored.

Particularly attractive at the ICP show was a scaled-up photographic series that provided an intimate look into three experiences of domesticity: the U.S. Naval base, the Guantanamo cells themselves, as well as scenes from released detainee’s attempts to fashion new lives abroad. The bright sunshine of these lower latitudes can’t quite erase the lingering umbra of U.S. control. An empty green yard, an SUV parked by mosque, majlis-style seating in a sparse room, a pile of leg shackles, an autopsy room, a green pillow emblazoned with “Welcome home Omar.” The medium implies some modicum of objectivity— truth telling in the face of so much censorship—yet it is hard to shake the suspicion that these photographs are just as artfully staged as the FOIA’d documentation elsewhere in the space. Wherein Clarke’s framing—and his inevitable inclusions and elisions—takes the place of censor’s black marker. But strangest of all: Guantanamo looks—feels—so much worse when looking out onto the imagined sea through the optimistic eyes of the detainees rather than in the catalogue of deprivations (sometimes graphic) that is the Clark show.

The title of Clark’s show, “The Day the Music Died” references the Don McLean chronicle of national (then: Vietnam) shame, “American Pie” and recurs in a wall decal of songs used to disorient detainees during interrogations. (The playlists includes the Barney and Friends theme and several Eminem songs). The song also soundtracks visitors’ descent into the basement exhibition; to enter, you must first pass through a rewarding historical exhibit on Japanese internment camps. The pairing sets up a cogent historical parallel, both in their depictions of daily life in the camps, as well as in a comparison of language used. An evacuee/internee is now an inmate, detainee or prisoner, for example, while an assembly centre is now a temporary detention centre. A recent Supreme Court ruling suggests that even if Guantanamo does one day close, for immigrants, being infinitely detained forever prisoners will continue to be the norm.