With FUZE at Baha Mar, the Bahamas is building a new foundation for its art world, linking local experimentation to global recognition at the Venice Biennale

The walk to the FUZE Art Fair isn’t short. From my hotel room at Baha Mar, it takes nearly fifteen minutes through a warren of corridors, across the towers of three hotels, and through a casino. Its floors are devil red, patterned to keep you disoriented but in motion. Casinos are designed with certain principles in mind: no clocks, no sharp turns, oxygen-rich air pumping through the vents to keep you alert. Everything is calibrated to disarm the parts of the brain that make you stop and reconsider. As I weave through the slot machines and card tables, I wonder whether any of that same science will make its way into the art fair. The expectation, walking in, is that it might.

But FUZE turns out to be something else entirely. The fair feels improbable, an event devoted to Caribbean art and dialogue staged inside a resort on Nassau. Now in its third edition, the FUZE Caribbean Art Fair has become a center of gravity for the region’s cultural scene. This year’s edition made headlines with the opening-night announcement that Lavar Munroe and the late John Beadle will represent the Bahamas at the 2026 Venice Biennale—only the second time the country will have its own national pavilion, the first being in 2013. For a young, small island nation of just 400,000 people, the announcement marked a breakthrough moment, signaling the viability of Bahamian art for the global stage.

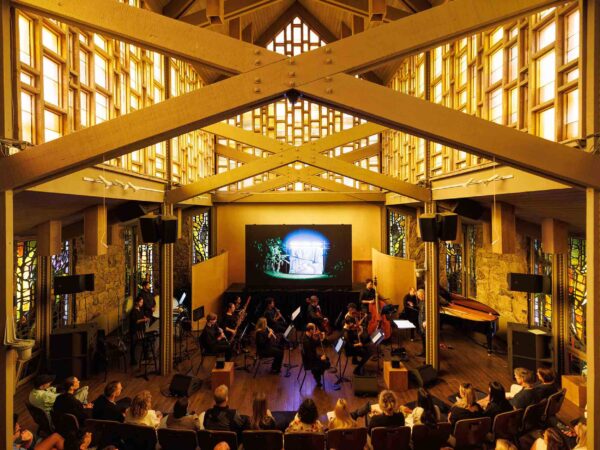

The partnership between Baha Mar and the country’s cultural agencies has been key to that ascent. The resort, which houses one of the Caribbean’s largest art collections, provided every booth at FUZE free of charge, making it possible for artists, galleries, and institutions from across the region to participate. It’s an inversion of the typical art fair model, more meeting ground than art market. John Cox, Executive Director of Art & Culture at Baha Mar, has been described by participants as a kind of quiet architect of the region’s new cultural infrastructure: an artist using corporate patronage to engineer access. “It means so much for us to put this platform together—to be able to work with all these artists and build a sense of community and collaboration across the region,” Cox said in opening remarks at the fair. “The theme this year, Harmony, was about exactly that: the need to hook arms, to work together. We all know that people in the greater community succeed because they connect.”

That access was felt immediately. For Yasmin Hadeed, who runs Y Art Gallery, Trinidad’s only dedicated contemporary art gallery, the invitation was very welcome. “We feel so isolated,” she told me from her booth, surrounded by Trinidadian painters and sculptors. “Coming here, it’s like, okay—we can do it. What are we doing next? There’s a broader vocabulary for us now.” Hadeed’s gallery, like others across the Caribbean, doesn’t often show work internationally. At FUZE, she wasn’t alone. The National Gallery of Jamaica and Alice Yard from Trinidad joined in, sharing space and conversation with Bahamian, Barbadian, and Caymanian artists. “It’s a regional conversation curated by people who work in the region,” said Monique Barnett-Davidson, senior curator at the National Gallery of Jamaica. “We have not just artists from the Caribbean, but also from the diaspora. It gives you a microcosm view of what the Caribbean ecosystem is like.”

Blue Curry, a Bahamian artist known for his conceptual critiques of tourism, pointed out the rarity of such a moment. “It’s really difficult to be a gallerist in the region,” he said. “Most places that call themselves galleries are tourist souvenir shops or frame shops. So the fact that Yasmin, a serious gallerist, can come to an art fair like this—it’s her first time—John has created the format.” The fair’s structure, he added, “creates space for an ecosystem that didn’t exist before.”

I met a married couple, collectors from Brooklyn who had flown in specifically for the fair seeking out African and Caribbean artists. A woman I met on the plane, a finance executive from New York, was attending for the third time. Not to buy art, but as part of an annual girls’ trip. “Lenny Kravitz brought us here,” she said, laughing. The next evening, I found myself standing beside Munroe and the hotel’s arts director as Kravitz rehearsed for his performance. He sang “It Ain’t Over ’Til It’s Over” to an intimate audience consisting of stage crew, the hotel manager, a sponsor of the fair, Munroe, and myself. It was a surreal moment, art, luxury, and sincerity folded together. That is FUZE’s peculiar magic as a small up-and-coming festival.

In the Bahamas, artmaking has long been synonymous with Junkanoo, the annual carnival of parades and towering floats that spill through the streets on Boxing Day and New Year’s. Recognized by UNESCO in 2023 as part of the world’s Intangible Cultural Heritage, Junkanoo traces its origins to the late 18th century, when enslaved Africans in the Bahamas were granted a brief respite around Christmas to celebrate their freedom through music and masquerade. It’s the country’s most accessible form of creative expression, a fusion of sculpture, costume, and choreography with competing groups and loyal fans. During the fair, Munroe invited me to visit a Junkanoo shack in a former slaughterhouse on the island, where artists work almost year-round on their floats and costumes. Inside, a dozen people showed us their projects with great pride: over fifteen-foot-high structures of metal, cardboard, and colored felt paper. Some floats were shaped like Hindu temples, others like teddy bears and hearts.

The man designing the teddy bear float tells me his work is a dedication to his mother. Later, a guide tells me that, outside of the shack, the teddy bear designer is a dangerous, feared person. In Junkanoo, the social hierarchy collapses—doctors, janitors, gangsters, and government sons all answer to the most creative person in the room. After the Junkanoo shack, I began to understand FUZE differently.

“We’re creating a blueprint…The first pavilion was largely led by foreigners. This time it’s 100 percent Bahamian—Bahamian curator, team, production. We can do it ourselves, and we can excel at doing it.”

If Junkanoo is how most Bahamians first encounter art, FUZE might offer them a second way. Throughout the weekend, groups of Bahamian schoolchildren were given tours of the fair. “You could see their eyes light up,” Curry said. “That’s what’s most important.” For Hadeed, the moment echoed the purpose of her own gallery back home. “It’s about exposure,” she said. “When the kids see this, they can imagine themselves in it.” Those scenes of discovery repeated across the fair’s aisles—artists explaining their work to students, curators leaning in to offer context, hotel staff stopping on their breaks to look.

But the fair isn’t without tension. For years, Curry—a fixture in the Bahamian art scene who has exhibited at Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the Liverpool Biennial, among others—had refused to participate. He felt conflicted about showing in a resort that symbolized the very tourism industry his work critiques. “For my entire career I’ve made work that engages with tourism and the stereotypes around the Bahamas,” he told me. “I was conflicted. But this year, I proposed something critical of the resort—and they let me do it.” His project was a suite of seven vinyl stickers, each printed with short provocations: Decenter Resorts and Paradise LOL. “All of the art in this country can’t be filtered through the resort,” he said.

Curry talked about the kind of work that can survive in a corporate space like this. A resort comes with rules—spoken and unspoken—about tone and what’s acceptable. “We’re not going to have a performance here of a naked woman writhing in ketchup,” he said. The point is structural: once a resort becomes the center of national art, the art adapts to the environment that enables its financial feasibility. “That’s the danger,” he said.

For him, “decentering” is about preservation, building other places for artists to take risks. He imagines studios, warehouses, artist-run initiatives, even informal gatherings that can exist alongside Baha Mar, so Bahamian art doesn’t become synonymous with the resort’s walls. “We need more than one locus of art,” he said. “We need a network.”

The stakes are high. Without alternative spaces, many of the country’s leading artists build their lives abroad. Munroe spends most of the year in Maryland; Curry lives in London. Both maintain deep ties to Nassau but rely on other cities to sustain their practice. “That’s the irony,” Curry said. “We’re showing that Bahamian art can operate at the highest level—but to do that, we’ve had to leave.”

Sales at FUZE, by most accounts, were modest. “Selling is difficult in Trinidad too,” Hadeed told me. “We share the same struggles. But it’s not about that—it’s about being here, meeting people I would have never met.” Curry agrees that the fair’s impact isn’t measured in transactions. “It’s about showing that an art ecosystem is possible,” he said. The irony, of course, is that the fair’s very generosity—the free booths, the resort’s backing—is what makes that ecosystem possible at all.

“When I first moved from the National Gallery to Baha Mar, people said, ‘You’re going to lose the criticality of what you’re doing,’” Cox recalled. “But I believed we could be critical—we could reimagine and recontextualize the spaces we were in, and use them to project ourselves forward.”

That such a project as Curry’s was approved speaks to FUZE’s paradox, a luxury resort willing to host its own critique. It is a sign of maturity perhaps; a recognition that national culture can’t grow without dissent. Still, Curry worries about access. “There are lots of people who are not going to come onto a resort property,” he said. “They don’t feel comfortable in this space.” For those who do, FUZE offers a glimpse of possibility that a Caribbean art world might exist locally, amid the contradictions of paradise.

Amanda Coulson, founder of Nassau’s TERN Gallery and former director of the National Art Gallery of the Bahamas, sees those contradictions as the point. “It allows artists to see they’re not alone,” she said. “They can have a career and stay home. For those kids to grow up finding that normal—that’s huge.” Coulson also helped coordinate the upcoming Venice Biennale pavilion, which will pair Munroe’s work with materials left by Beadle. “Some of John’s Haitian sails will be shipped to Venice,” Munroe told me. “I’ll combine them with Junkanoo costumes left on the street after Christmas to make a site-specific work.” The sails—salvaged from migrant boats crossing from Haiti to the Bahamas—speak to the region’s intertwined histories of migration and labor. “John was disturbed by seeing Black bodies still packed onto boats by Black people,” Coulson explained. “His work was about emigration, loss, and the souls at sea. Lavar’s extending that conversation.”

Munroe describes the Biennale as a turning point. “We’re creating a blueprint,” he said. “The first pavilion was largely led by foreigners. This time it’s 100 percent Bahamian—Bahamian curator, team, production. We can do it ourselves, and we can excel at doing it.” That same ethos—self-determination built on collaboration—runs through FUZE. As a corporate space creating room for critique, a tourism engine opening its doors to the local public (if they can can afford it), a commercial space facilitating regional cultural exchange on its own dime, a luxury resort functioning as a national cultural center.

In a country where state funding for the arts is minimal, the resort has become both patron and platform, absorbing the responsibilities of a ministry of culture. Baha Mar is a lead sponsor of the Bahamas’s Biennale pavilion, and FUZE’s open structure—the free booths, the regional invitations, the willingness to engage criticism—reveals a way for hospitality to deepen its function as cultural infrastructure. Still, it raises an uncomfortable question: what happens when national identity is shaped by private enterprise?

For now, the results are remarkable. The Bahamas will arrive in Venice next year as a small island nation articulating its creative sovereignty through both public partnership and private will.

On the last night of the festival, I blew $20 on a Whitney Houston themed slot machine. In the thick of the gambling thrum, I thought of that Junkanoo shack, the web of collaboration, the shared purpose that momentarily restructures hierarchy. FUZE, too, runs on that rhythm as a collective project—unexpectedly beautiful, built from contradiction and dedication.

“By the year 2020,” Cox remembered his mentor Jackson Burnside saying, “more people will come to the Bahamas for its art and culture than for the sun, sand, and sea.” He smiled. “That’s still the mantra for so many of us. It’s what drives this work.”