The British artist draws from Surrealism to empower women to reclaim their “birthright” to sexual expression and deconstruct oppressive structures of power.

For over 50 years, British-born American artist Penny Slinger has dedicated her practice to exploring the fantastic nature of the feminine psyche. Her efforts have now culminated in Inside Out, a captivating exhibition featuring four bodies of Slinger’s work throughout the 1960s and 70s, opening February 7 at Fortnight Institute in New York.

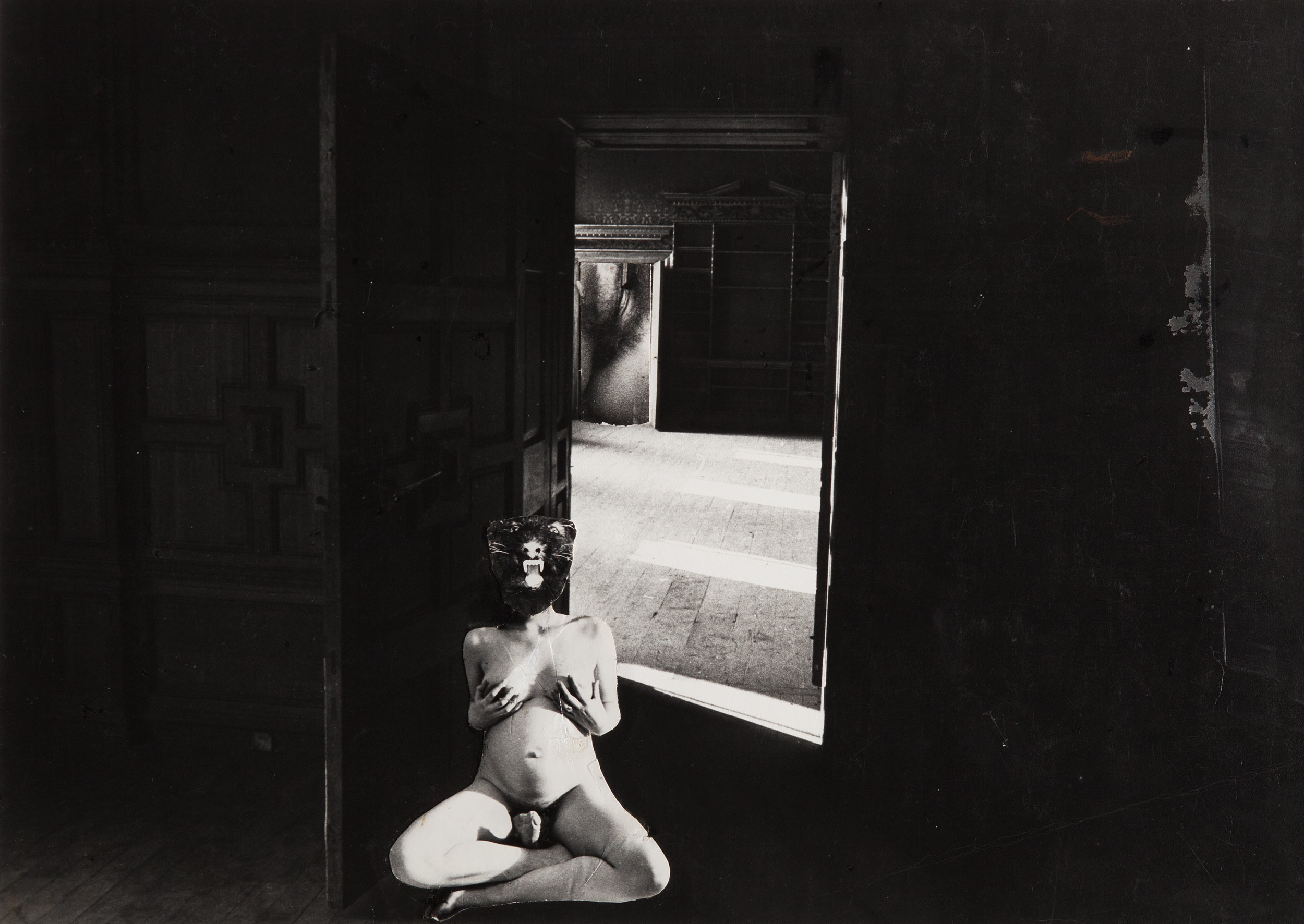

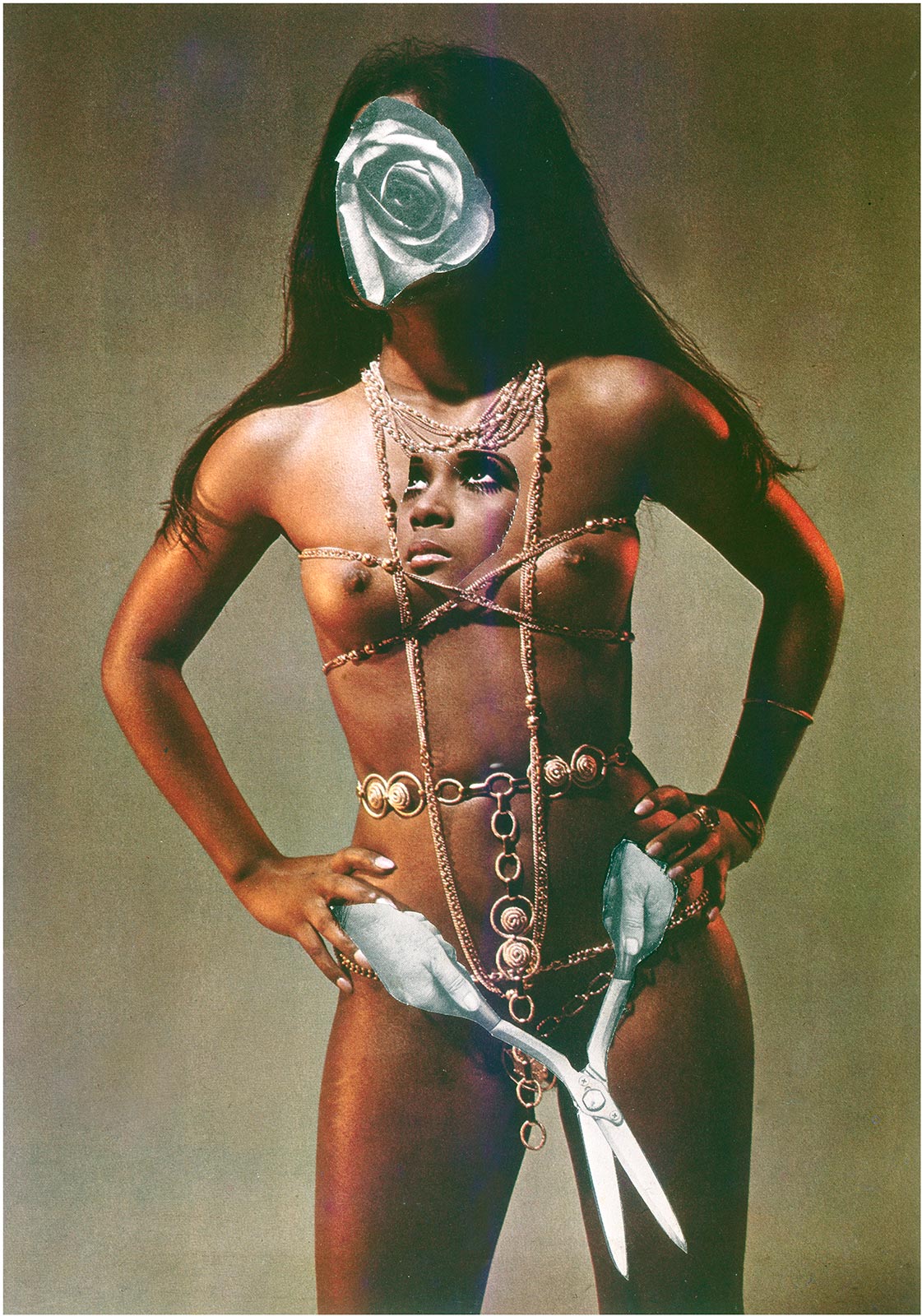

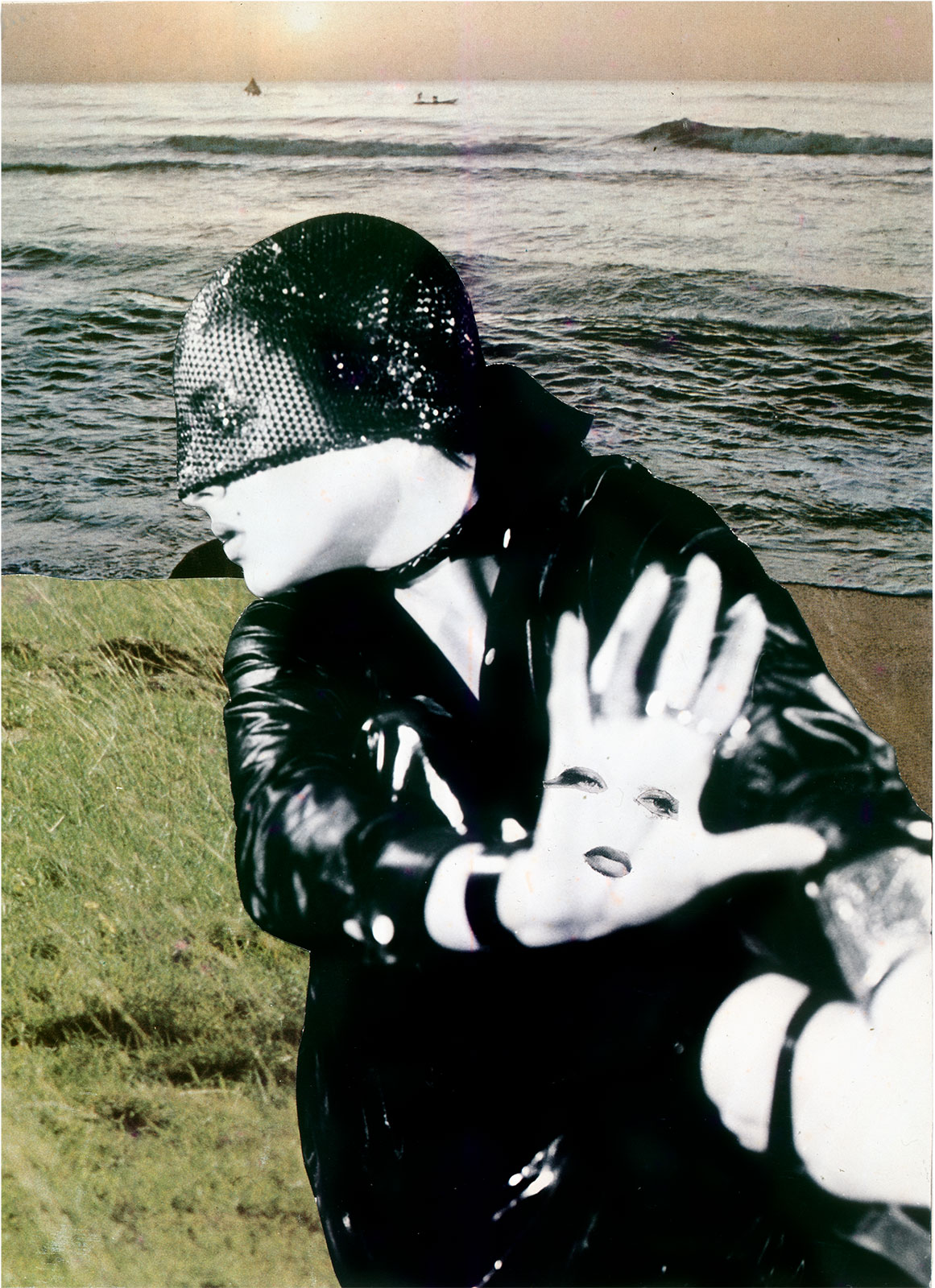

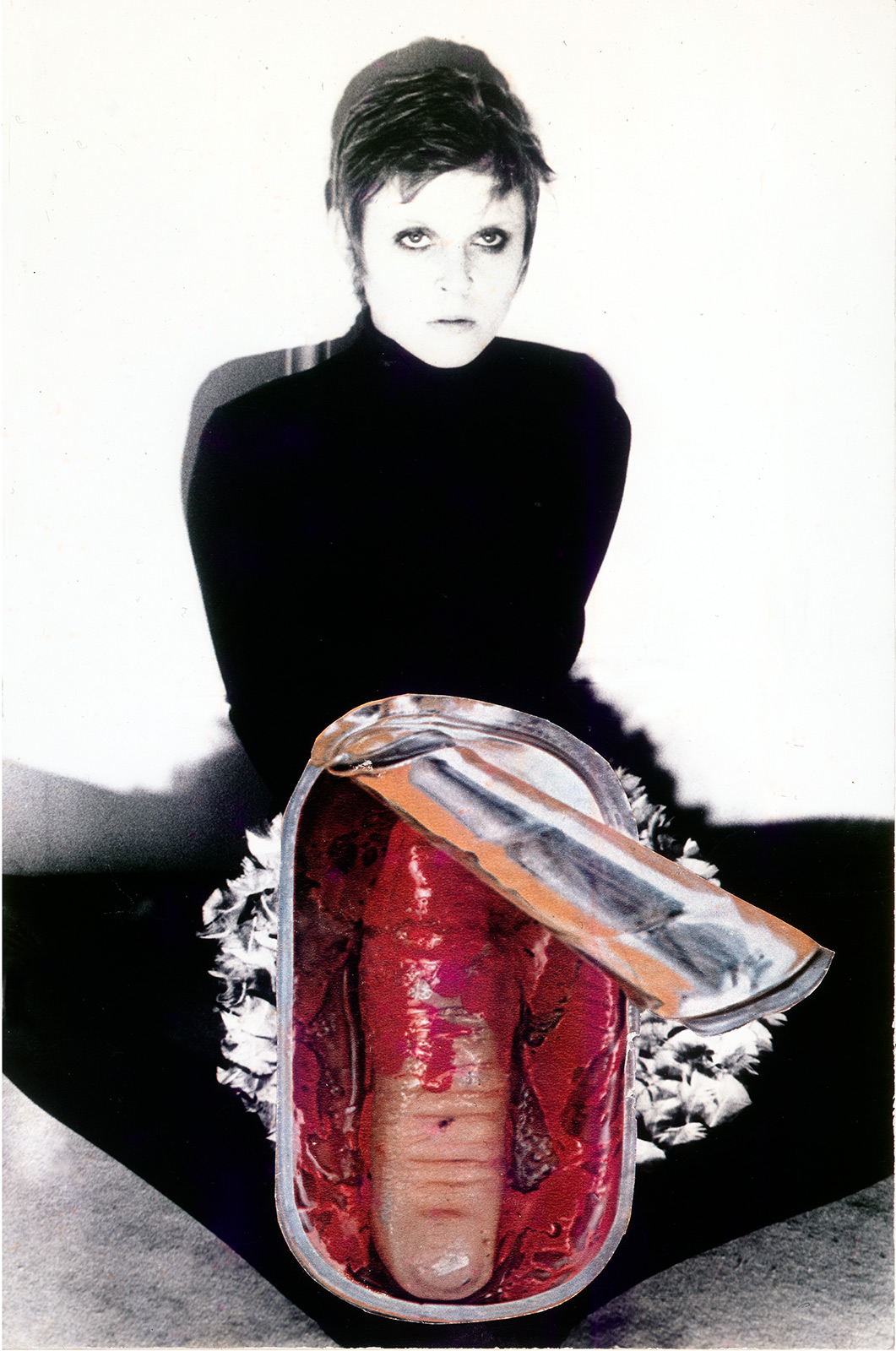

The exhibition grounds itself in the mediums of film, collage, and photography, the two latter of which, when combined by Slinger, make for a highly sensorial experience. Photography collages pierce and distort our traditional sense of reality by juxtaposing sharp scissors or bloodied fingers over intimate parts of the female body such as the woman’s face, breast, and vagina. This contrast of soft and destructive becomes emblematic of Slinger’s ability to confront stigmas of female sexuality as “shameful” and “forbidden” head on, and beautifully usurp these false connotations with the driving image of a woman as beholding a diaphanous energy within her body that is inherently sensual.

Aptly named, Inside Out implores its viewer to look towards their innate, mystical selves to unlock a connection to the natural world that can be felt with a profound sense of sensuality and eroticism. The exhibition, presented in collaboration with Blum & Poe, is a reminder to women that self-exploration endows us with the power to reclaim our own divine essence and asserts a subversive new form of reality that allows women to be their own muse.

Kaylee Warren—Surrealism inspires the way you approach the feminine psyche in your work. Do you think the experience of being female is an inherently surreal one?

Penny Slinger—Well, I think the tours of surrealism are a very good way to probe the feminine psyche. A lot of people talk about the sexuality in my work, but I’m really interested in the psychic striptease, which gets below the skin into what’s going on inside. So in that case, it is surreal because we’re painting a landscape of dreams and imaginings and all the things which aren’t necessarily a part of the mundane world but definitely a big part of who we really are—our intuitive selves and our mystical selves and our sensual selves. As women [these selves] are very intertwined, and yet there hasn’t been much of a platform for it. That’s what inspired me to bring that to the light of day, using the way that surrealists molded reality in new combinations so that we are then cracking open the way that things originally seem. Through that crack, you are lifting veils into all these layers and levels that are a part of our much bigger beings.

Kaylee—The exhibition is a collection of works you created during the 1960s and 70s. How has your understanding of the feminine psyche evolved since then, if at all?

Penny—That’s a big question. I think in a way we come in as complete beings and, yes, we grow and evolve throughout our experiences, but I think we’re kind of an imprint of who we are—whether its from past lives or just a bigger collective pot that we dip into to mold our beings as they come into manifestation. As I got a bit older and wiser, that scope became broader. Surrealism was a very big effecting thing for me because I saw the ways of using collage—for me photographic collage is really important—to show something more than just the world of appearance. Then that developed into tantric art. I know tantra has become a big influence in modern life, but mainly just the sexual side of tantra. But actually tantra means “to weave” or “to expand.” It’s like weaving all the parts of yourself together and expanding into a more multidimensional view of yourself. As I grew up, I got to know more about that and incorporated that into my whole way of seeing.

When I was living in the Caribbean, I was studying indigenous culture—the Arawak Indians who were there before—and how they relate to nature and the world. All of that informed my way of seeing things because I think in modern life, we don’t really see the spirit in all things, the sacredness of everything, the sacredness of the body. That is, to me, a big part of the feminine, which we need to reclaim. All of these things have woven into my experience. In the work that I’m doing now, I’ve come back to using myself as my own muse as I did early on. Using my body now and my psyche now and I’m calling my new series “Mind, Body.” It’s my body of experience. Into that comes all the impressions I’ve had in my life combined with all those knowings that I really had right from the start, and just finding ways to interpret and share that in a communicable way.

Kaylee—That leads into a question I had about you seeing yourself as your own muse. I think that’s incredible. Tell me more about that.

Penny—I was studying the history of art when I was about to do my thesis at Chelsea, and I found that throughout the history of art, Woman as The Muse has been a very important and central theme. The naked woman is being seen through the lens, usually, of a male artist. The history of art has been filled with male artists and not so many women. So I thought, “Here I am I’m a woman, I’ve got my own way of seeing.” I wanted to reinterpret this role of the muse. I wanted to be the one who sees as well as the one who is seeing. I wanted to be in two places at once and presenting how I see myself. I thought this was a really important part for women to claim, and that’s a very central piece of my work. Working with other women [is another central theme of my work] which I’ve done a lot in my life [and is a] reflection of how we can see ourselves in each other and empower each other rather than competing with each other.

Kaylee—Yes, because women are all connected. It goes back to what you were saying about the spiritual experience of being a feminine being in which you are unraveling all of the parts of yourself to get at something deeper.

Penny—Exactly. The muse is really a spiritual entity, an inspiration that speaks in your mind. The male artist has often used physical women to express that, and I thought that we need to express ourselves now, to claim that back, to be in that dynamic with our own reflections as something, then, that can be this amazing Hall of Mirrors that can only infinitely multiply those views of self into something that can be much more expansive again.

Kaylee—That ties into the ways in which you are aiming to dismantle oppressive power structures through your work.

Penny—In [my] first book, 50% the Visible Woman, I did this series of collages—and we have a number of these reproduced in the exhibition—in which I was making a study of how women are seen both by society and the media as well as by the art world. Trying to get through this objectification and to claim one’s position as subject as one’s own world and one’s own art.

Kaylee—It’s interesting how this work was originally created during a period of widespread political upheaval. 50 years later, to describe current affairs as “political upheaval” would be to put it nicely. Would you describe your work as dissociative? An escape from the political turmoil happening around us?

Penny—I believe that there is no political change outside until you make that political change inside. It’s those dynamics and the politics of experience that are the real keys to change. If we don’t do that in our work, if we don’t shatter all the templates we’ve been put in, we don’t really have a good chance of making things change outside. When there is a change or upheaval, those who want to lead the way in terms of consciousness need to be able to put themselves on the line—body and soul—and show the innerworkings. I have always used the art as a tool for that. I’m not keen on propaganda art because I find that it loses in its timeless value. So while I created [my works] within a political climate, I believe they still resonate because you touch things that are a little bit timeless. Only when you do things that really are about inner change do you have something that’s going to last; otherwise, it’s just the wave of things that come and go.

“Inside Out” is on view at Fortnight Institute until March 17, 2019.