Political scientist Brendan Nyhan explores where the democratization of information and freedom of choice turn sour for Document's Spring/Summer 2017 issue.

Critics of democracy have long lamented that people know too little about politics, but today we have more news and information available to us than at any moment in history.

I, for instance, start and end my days with Twitter: The ongoing stream of information it provides about the world is a relentless and sometimes oppressive presence in my life. Even my less politically obsessed friends and family members now find that the news has become an ongoing part of their days via the Facebook posts, push alerts, and other manners information finds its way to the devices and screens that surround us.

They aren’t unique. According to a study from Pew Research Center in July 2016, 38 percent of American adults say they often get their news online. In particular, more than seven in 10 people get some of this information on their mobile devices, which have brought the news into parts of our day to day lives where it used to be largely invisible. Similarly, nearly 60 percent of adults say they often or sometimes watch cable news, which increasingly permeates common spaces like airports and coffee shops, making the news harder to escape even if we do not seek it out.

At a personal level, these trends can be discomforting. Surveys sponsored by the American Psychological Association found that people who frequently check online information sources are especially stressed. Though it is impossible to separate cause and effect in these data, it is noteworthy that approximately four in 10 of those “constant checkers” cite political and cultural controversies as a specific cause of stress. Overall, 57 percent of Americans report that the political climate is very or somewhat stressful. What is understood even less is how this deluge of information is affecting our lives as citizens. Are we truly better informed? Or are we becoming a nation of political amnesiacs, stumbling blindly from one breaking news event and meme to the next?

Getting more news and information might seem to be beneficial. The best political journalism is now easily accessible to people all across the world, including fact checking organizations that assess the accuracy of claims made by politicians and pundits on a daily basis. Online news might also increase the likelihood of people having chance encounters with news they would otherwise avoid. The political scientist Markus Prior has shown how the rise of cable and the decline of newspapers in the past reduced people’s exposure to “hard news,” which previously could be seen on the front pages of morning papers or during network and even news broadcasts. These types of unplanned encounters are an important way to promote news exposure among individuals who do not seek it out and can reduce inequality in political knowledge.

Social media and online news also offer new opportunities to distribute information and organize politically. The widespread distribution of online videos of police violence and brutality played a key role in drawing increased public and legislative attention to the issue. Similarly, the first weeks of the Trump administration featured widespread efforts to organize protests, call congressional offices, and attend town hall meetings that were primarily organized online. The feedback loop between observing a news event, sharing information about it, and engaging in offline political action is potentially faster than ever before. Engaged citizens may therefore be empowered to intervene more quickly and effectively than they could in previous eras.

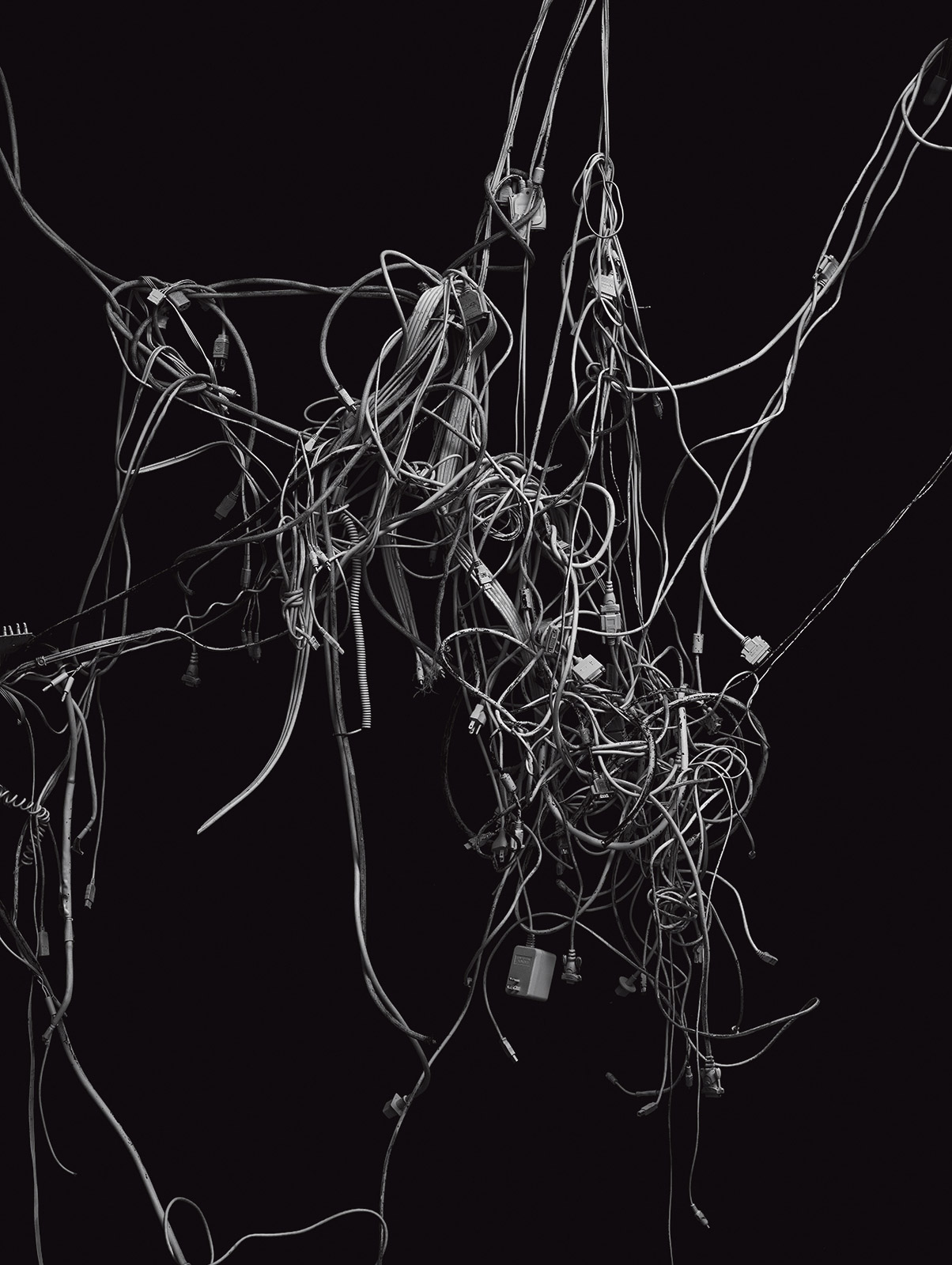

However, the accelerating news cycle, which has become a drumbeat in the lives of smartphone carrying citizens, may also have pernicious effects on both our view of the world and the content of public debate. It can distract us from or crowd out stories of greater importance, accelerate the spread of rumors and false information, demobilize and confuse us, and trap us in a partisan echo chamber: As we revisit the meaning of citizenship in a digital age, society must address all of these challenges.

“If everybody always lies to you, the consequence is not that you believe the lies, but rather that nobody believes anything any longer.”

First, while we are all distracted by the latest outrage or clickbait headline, we may miss—or choose to avoid— more important but less viral stories about the world. The speed with which new stories rapidly supplant previous ones online and the way in which we select the articles we read online may affect the types of news we encounter and the problems we see as important. One experiment, for instance, found that online readers of “The New York Times” encountered less public affairs coverage and rated international problems as less important than print readers. The relentless pressure to produce new content that commands the attention of fickle news readers means that even significant stories can quickly fade from the headlines if they do not generate a continuous stream of new developments. In other cases, the speed of the news cycle and the way it can be dominated by a handful of stories can crowd competing stories off the news agenda entirely or even prevent new stories from emerging. For example, social science research has demonstrated that congestion of the news in the wake of major events like the 9/11 terrorist attacks and Hurricane Katrina can crowd out news of other events of foreign disasters and even influence the likelihood of U.S. disaster relief as a result.

News congestion of this sort can also crowd out presidential and gubernatorial scandals here, as I have found in my own research. In some cases, the stories that are being displaced are trivial or tawdry—the death of the singer Michael Jackson, for instance, helped save South Carolina governor Mark Sanford from an extramarital affair scandal that previously received saturation coverage. However, in other circumstances, stories that deserve public scrutiny never receive adequate attention in the press. Joshua Green from “Washington Monthly,” for instance, marveled at how long Army Secretary Thomas E. White, Jr. lasted in office during 2002 despite multiple ethical concerns about his background and behavior. Too much news was being made in the months following 9/11 for the media, the public, or Democrats in Congress to pay much attention to him. Similarly, President Donald Trump seemingly exploited these news congestion dynamics during the 2016 campaign and its aftermath, creating so many stories each day that neither his opponents nor the press were ever able to focus on any particular aspect of his record or background. As a result, numerous potential scandals that might have been career ending for other politicians were quickly displaced from the news before much damage ensued.

The speed of the online news cycle, and the contexts in which many people now encounter news, can also make us vulnerable to misinformation. These dubious claims can originate from mainstream outlets, which face pressures to keep up with competitors and to generate shareable content, as well as fringe or alternative sources. When citizens encounter these stories, they often share them on social media, helping the misinformation to spread even further. Numerous false reports circulated in mainstream outlets and online, for instance, during the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombings in 2013 as reporters and citizens raced far ahead of the set of verified facts. Similarly, the most prominent “fake news” stories were more widely shared on Facebook in the months before the 2016 presidential election than the most shared stories from mainstream news sites. As a result, millions of people saw stories such as “FBI Agent Suspected in Hillary Email Leaks Found Dead in Apparent Murder-Suicide” without knowing they were fictitious. Our vulnerability to these dubious claims may also be enhanced by the way we increasingly get information. People are often distracted when using mobile devices. Despite many people’s beliefs that they are good at multitasking, humans struggle to process information effectively when their attention is divided.

In some cases, the prevalence of questionable or dubious information may affect people’s willingness to participate in politics or even try to make sense of it. Political scientists often measure Americans’ beliefs about whether they have the ability to affect the political system, a concept known as “political efficacy.” While our confidence that we can make a difference politically may be threatened if the world feels too big and complex, another concern is even more basic. Does the cacophony of the online news cycle threaten people’s confidence that they can discern the basic facts about politics? This concept, which the communication scholar Raymond Pingree calls “epistemic political efficacy,” could be called into question as audiences are increasingly reminded how much they do not know or understand about the political world.

This kind of demobilization through information overload can even be intentionally manipulated by elites, especially when claims made by political figures are so frequently misleading. Back in 1974, Hannah Arendt described how this process can work in the case of an authoritarian regime: “If everybody always lies to you, the consequence is not that you believe the lies, but rather that nobody believes anything any longer…And a people that no longer can believe anything…is deprived not only of its capacity to act but also of its capacity to think and to judge.” These concerns have resurfaced recently with the rise of Trump, who has flooded the media with numerous falsehoods and repeatedly denied media debunkings of his claims, leaving many people in a state of confusion about who or what to believe. These circumstances may produce a kind of informational paralysis in which people cannot arbitrate between competing versions of reality. As a result, the role of facts in political opinion formation and vote choice could be further diminished, forcing voters to rely on partisan or group cues even more heavily than they already do.

Finally, the proliferation of choices in news outlets offers new opportunities for people to immerse themselves in partisan and ideological echo chambers. We are all vulnerable to the tendency to seek out like minded information sources and avoid those whose content is less congenial to our views. In some cases, those processes occur automatically—algorithms on Facebook tailor the content we see in the news feed to our preferences, for instance, which increases the frequency of like minded content being shown to us. In other cases, people engage in this process of selective exposure on their own, though the extent of this practice is limited among the general public. Research by New York University’s Andy Guess shows that most people are not engaged enough with political news to seek out a skewed information diet. However, smaller groups of people on the left and right do display strong tendencies toward like minded news sources. These are the same groups that are disproportionately likely to vote, contribute to campaigns, volunteer, et cetera. As a result, the echo chambers they inhabit may have disproportionate effects—a pattern that can be exacerbated by news applications and social media platforms like Twitter that can generate minute by minute reinforcement of one’s views. These chambers can in some cases be not only polarizing but dangerous, creating contexts in which conspiracy theories and hate can fester. A bizarre claim surfaced online in October 2016 that hacked emails from Hillary Clinton’s campaign chair, John Podesta, showed that a pizza parlor in Washington, D.C., was a front for a child sexual abuse ring. This absurd conspiracy theory attracted more adherents until a man who read about it online got the “impression something nefarious was happening,” and showed up at the restaurant with a rifle. (Fortunately, he surrendered before anyone was harmed.)

All of these challenges are difficult for citizens to address individually. We can strive to refine our information diets, but none of us have the time to fact check every article we read or to seek out every story that is not being covered adequately. Journalists and technology platforms must therefore help us to become better citizens and news consumers. In a world of information abundance, we need help not just to find out the news but to distinguish between low and high quality information and between stories that are genuinely important and others that are merely timely. In that sense, we have to figure out how to handle information overload not just as individuals but as a society.