An intimate tour of Christie's acclaimed Rockefeller Auction, this past May, revealed the lie at the heart of estate sales—and of the American dream so famously lived out by the philanthropic family

It’s easy to confuse knowing someone’s aesthetic for knowing who they are. Particularly with people of power, we presume their taste for rare objects and artifacts punctuate a knowledge of culture, or some direct connection to their congenital history. Before arriving to the preview of the Peggy and David Rockefeller Collection at Christie’s earlier this May, I’d cultivated my own idolized assumptions about the pair—after all they belonged to one of the most mythologized families in America. I wouldn’t realize how short-sighted my perceptions of worldliness were until encountering the brief, rehearsed scripts on the family’s legacy that filled the auction’s many rooms. There was a reason I had to keep a distance from the fine relics flaunted every which way: knowing less kept me seduced.

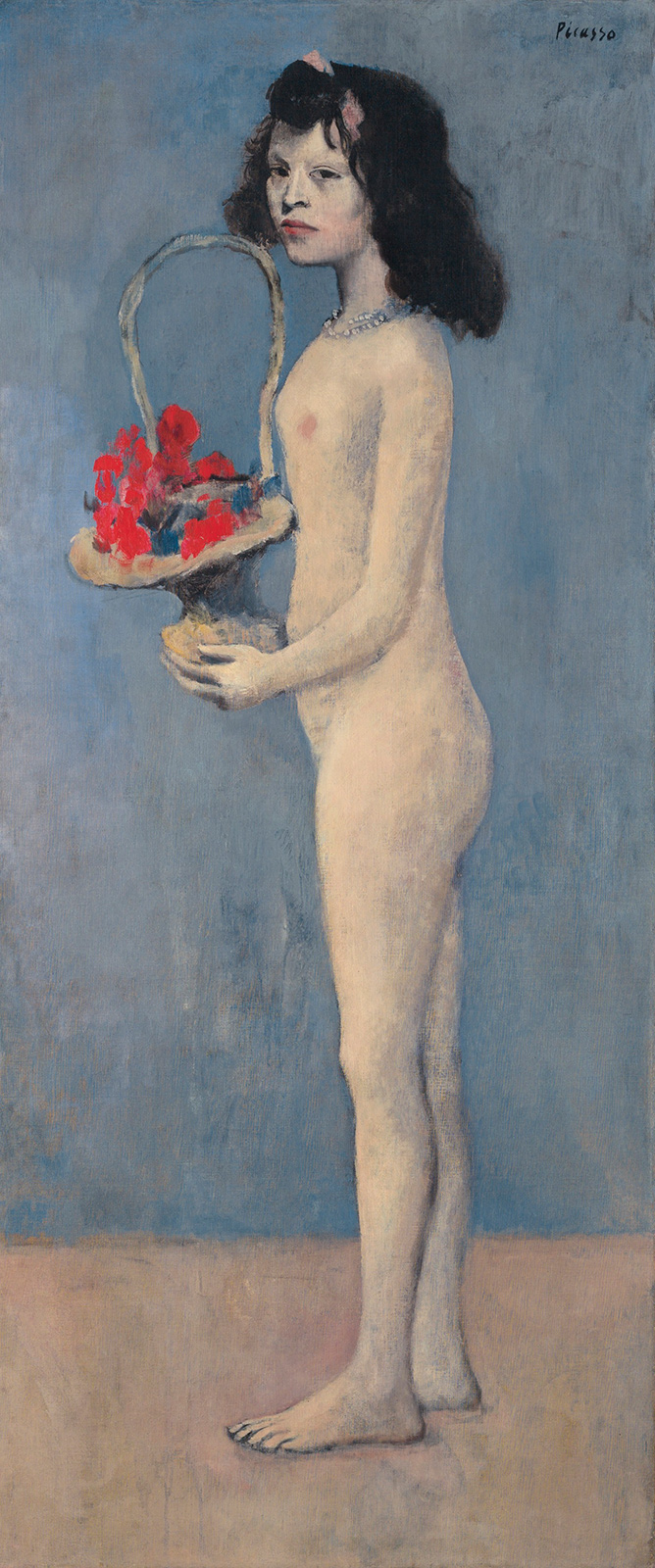

The tour began in a room full of hunting decoys sitting in disparate arrangements next to statues of Buddha, where I’m informed, of David Rockefeller, held lifelong investments in Chinese medical institutions. The guide, a lifelong family historian, jovially spoke of Abby Rockefeller’s love of Japanese tea houses, shuffling our group to the other side of the room to coo and awe at the encased blue and white porcelain. Quickly, we’re herded through rooms holding English and European Furniture, Dining Services, and Impressionist and American Art. Every household possession exhibited obvious if not greater historic importance—fine bowls from the Ming Dynasty, horse carriages, Picasso’s Pomme personally painted for Gertrude Stein, an Ayyubid incense burner from the 13th century. Getting a glimpse of a piece like Matisse’s Odalisque couchée aux magnolias, which will likely never be shown in public light ever again, felt like an important enough reason to be there. Yet the only protruding information to accompany each piece was a price tag. Despite my proximity to a closed off society, it was clear I’d never know the true depth of the personal or political connections the Rockefellers had to any of these assets. The only information given to the Christie’s audience was never how did this get here, but how much.

This is the central fascination of any estate sale—shopping experiences held in the homes of the newly deceased, surrounded by their once-treasured memorabilia—for most, the transfer of one’s property to the highest bidder becomes a final, inexact transmission from a life of accumulated experiences and desires. Never mind that it’s maybe a bit disrespectful—a piece of historic context has gone missing between the time you purchase something and repurpose it. Estate sales of most middle-income families may be arranged to meet logistical needs rather than commemorative ones, but the Rockefeller collection is an unusual case. The Christie’s sale was an exhibition-cum-liquidation-sale sitting between vanity and charity. Exhibit A: Sponsored by VistaJet, the spectacle had already been exhibited in the art hubs of Hong Kong, London, Paris, Beijing, Los Angeles, and Shanghai prior to its arrival at the New York auction house. Over the course of the week, it attracted registrants from 53 different countries with 45 percent of bids coming across the telephone. On the first night of the auction, the highest recorded sale from a single owner collection—Yves Saint Laurent in 2009—was broken, with the Rockefellers bringing in $646.1 million. By the last day, all 1,500 objects had sold for a total of over $832 million. These numbers are a foreign language to me. For someone like myself, the product of middle-income immigrant family without inherited estates, who has never dined with families like the Rockefellers and arrives to auction houses in her ex boyfriend’s Old Blue Last baseball cap and faded denim, observing the collection was more an act of voyeurism, as if I’d just trespassed into the home of the 1 percent. This is what I consider to be Christie’s best charitable act: giving the 99 percent an opportunity to see what they otherwise couldn’t even imagine.

One collection in the showroom stages an almost Disney-fied simulacra of the couple’s life together, reinforcing the narrative of upward social mobility and its greatest reward—imagery of an idyllic vacation far from life as the rest of us know it. Take a picturesque display of “a Rockefeller picnic,” where a trunk-sized basket filled with luncheon flatware (the whole set gifted by the King of Morocco, a family friend) was leisurely sprawled out against a scene of deserted turf. The sound of birds chirping filled the room, though there were no birds in sight except an altar of Peggy Rockefeller’s Chelsea porcelain hens and precious figurines. For a moment, the installation reanimates something that which will never materialize again—a life once lived. But instead of standing there in awe, I felt more like I was drowning in some eerie apparition, a fading echo of 20th century America. Is this one of the legacies left to us by one of America’s founding families, the gaudy lunch?

“This is the central fascination of any estate sale—shopping experiences held in the homes of the newly deceased, surrounded by their once-treasured memorabilia—for most, the transfer of one’s property to the highest bidder becomes a final, inexact transmission from a life of accumulated experiences and desires.”

There is an idea that the real treasures we stumble on amidst a life’s worth of possessions can only be found in the act of treasuring itself. In his poem In My Desk, Frank Bidart tugs at the notion when a character saves a dead lover’s cigarette butts in an envelope, turning them into both relic and fetish. These objects take on a beauty that, to Bidart’s character, becomes necessary. For all the Rockefeller auction’s memento mori and vanitas, the tour was devoid of sentiments like Bidart’s. My shallow understanding of the couple, and what it means to “Live Like a Rockefeller” remained unaltered. While the porcelain china in their dinner collection was dazzling, I was more curious about the stories that unfolded around these objects—who made them, how many times they were put to use, whether they sat in the presence of arguments over roasted branzino, what other persons, each with their own manifold stories, were served by them. So much of aesthetics plays a role in the construction of our world, but an auction like this seems to groom our emotional response towards the ornate rather than the inelegance that defines humanity, a life of interactions that cannot be quantified, bought or sold. The Rockefeller estate is a paradigm of capitalism’s lost translation of life lived. Perhaps, it’s this absence of life and humanity that cultivates certain value. An artwork becomes sensational as time passes or when an artist dies. Parks become more significant when demolished. Demand driven by lack stimulates market forces. A world of negations. In 1905, Leo, Gertrude Stein’s brother, acquired Picasso’s Fillette à la Corbeille Fleurie (Young Girl with a Basket) for $30. Over 100 years later, that same painting sold from this collection for $115 million. Nostalgia is, after all, a power that objects possess, serving as reminders of past eras.

In the same vein as Bidart, Mark Doty writes about our intimate relationship to the material in Still Life with Oysters and Lemon, which analyzes the omitted depictions of life and social activity in a 17th century Dutch painting by Jan Davidsz. de Heem. Doty asks why these omissions fascinate us. He contends that our relationship with objects fortifies itself in the face of loss and death. For Doty, his grandmother appears in every bowl of peppermint candy he sees, his mother in silver plates and all the ways she’d handle them. David’s own mother, Abby Rockefeller, was a woman who valued the ephemeral, and who had the means to capture it. In 1932, she commissioned artist Charles Sheeler to make a drawing of Central Park, a space that would soon face rapid changes thanks to the Rockefeller’s own interests in the landscape. Absent in Sheeler’s vista of the park are the reams of people, who walked through it everyday, the picnic-ing masses, the socialites luxuriating in the sun. Absent are the stories of life in a city practically owned by the Rockefellers, replaced by an object void of meaningful storytelling, yet brimming with aesthetic choices. The American dream embodied by the Rockefellers is really a bondage, it should be said, to the material. It traps us in capitalism’s greatest joke: the accumulation of one resource always requires the diminishment of another. Lost in the halls of Christie’s are the finite moments of discovery or inexactitude or humanity. They probably fell between the cracks of some 19th century armchair.