Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald's portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama are the latest entries in a visual tradition defining the politics of the present

The idea of the American dream started with the birth of the nation, when the Declaration of Independence declared that “all men are created equal” with the right to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” In 1931, James Truslow Adams wrote that “life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement” regardless of social class or circumstances of birth.” In their selection of artists to paint their official portraits for the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Barack and Michelle Obama broke with tradition, opting for Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, two black artists who embody the very idea of the American dream, to paint a first couple who are also products of this so-called ideal.

The two artists created portraits that caused a stir like no other unveilings previously. Wiley depicted the president on a wood chair before a backdrop of foliage that included flowers that told the narrative of his life—blue lilies from Kenya, the home of his father; jasmine from Hawaii, where president was born; and chrysanthemums, the official flower of Chicago, the city where Obama started both his family and political career. Sherald painted the former first lady in her signature grayscale, refusing, in a way, the notion that a person is defined by the color of their skin. Dressed in a Milly gown with a geometric pattern, Mrs. Obama showed that her dream is attainable by selecting a label that isn’t necessarily out of reach for the average American woman. Sherald noted that the ensemble referenced the geometric patterns of Dutch De Stijl artist Piet Mondrian’s paintings, as well as those in the quilts of Gee’s Bend, made by black female artisans from a small community in Alabama.

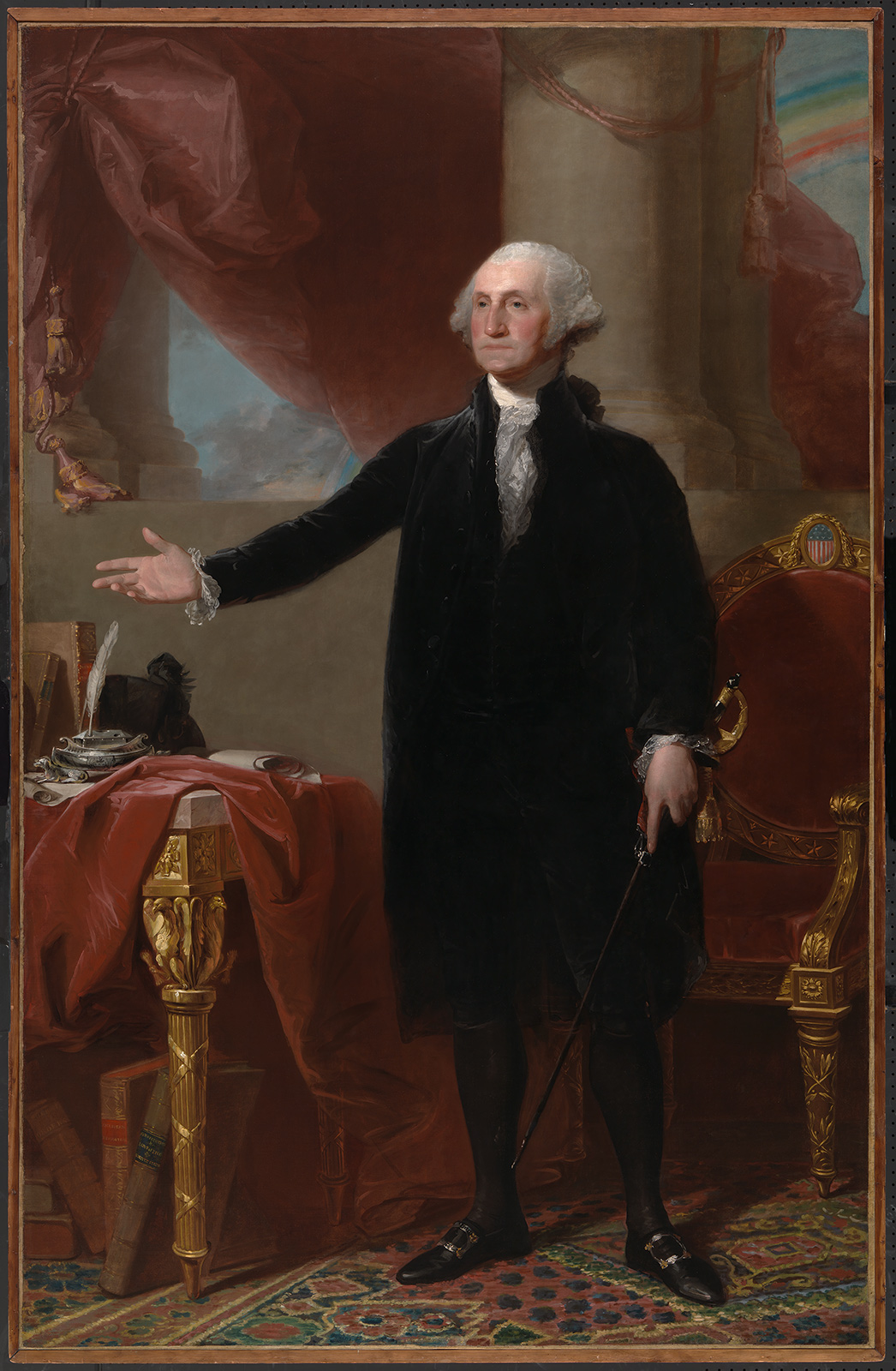

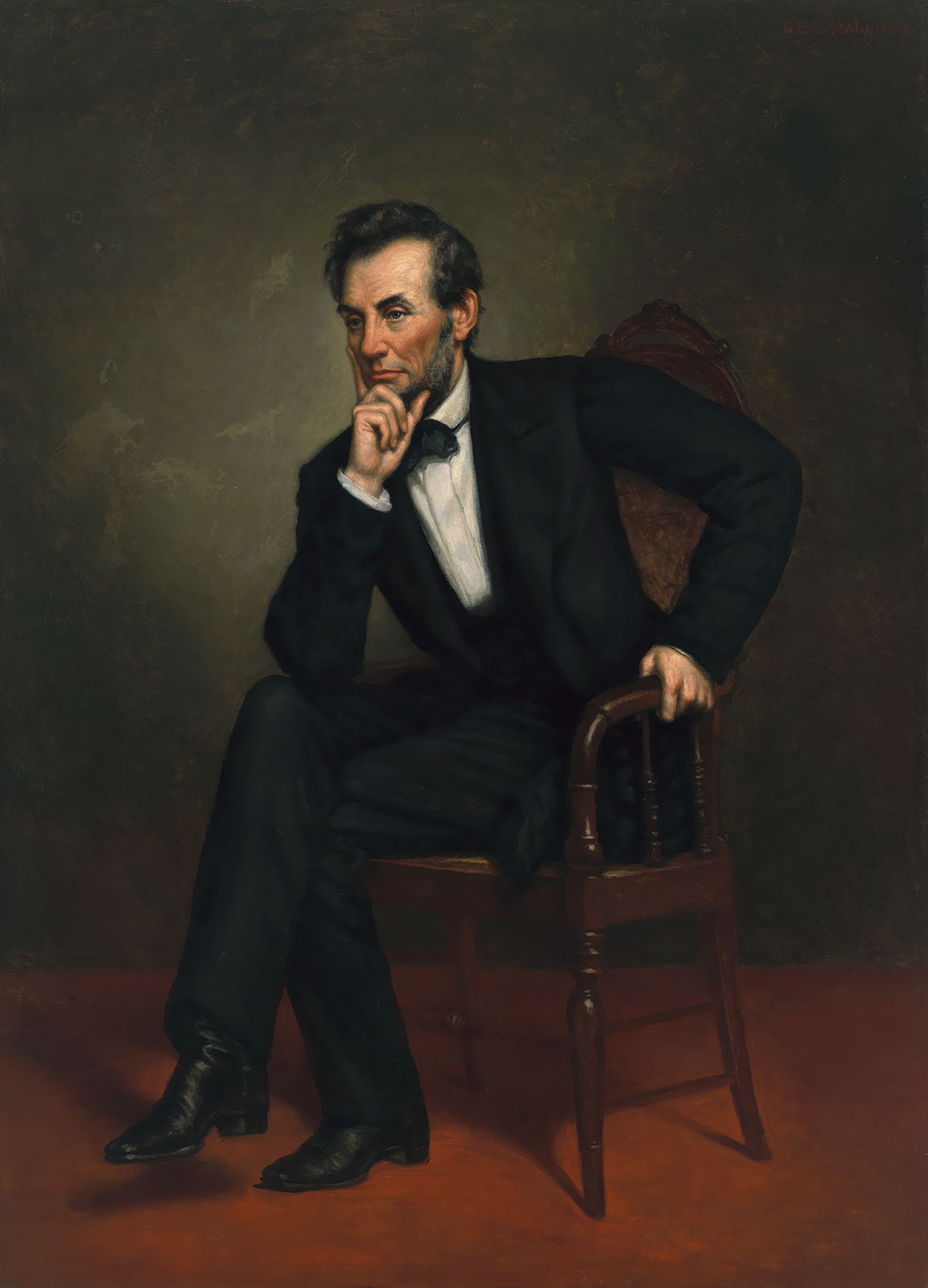

In the past, the standard presidential portraits look similar, depicting a white man before a stately background, usually with a serious look on his face. The vast majority of which are of a white man by a white man. At the entrance of the presidential portrait gallery in the National Portrait Gallery, a painting of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart from 1796 greets guests, the nation’s first president right hand outstretched as he stands before a throne-like chair, as if he’s welcoming visitors. Just behind it, an 1887 portrait of Abraham Lincoln by George Peter Alexander Healy, depicts the 16th president on a wooden chair in a contrived pose, his elbow resting on the right knee of his crossed leg as he rests his chin on his right hand.

Most of the critics who commented on the freshness of Sherald and Wiley’s portraits neglected to mention that a handful of artists before them strayed away from the norm. Douglas Chandor’s 1945 portrait of Franklin D. Roosevelt, which shows the top half of the President in a very fashionable fur-collared cape, a lit cigarette in a holder resting between his fingers. Below him, several studies of his hands show Roosevelt holding his spectacles, playing with a pencil, and holding a cigarette. Elaine de Kooning was one of the few women to paint a president, when in 1963, she created an image of John F. Kennedy that fused together figuration and abstraction, using a colorful array of gestural brushstrokes as the background. Even the President himself is comprised of fury-filled strokes, his face being the only defining marker of the subject’s identity. Finally, there’s Chuck Close’s 2006 painting of Bill Clinton, a headshot of the President infused with Close’s abstract pixelation.

Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

The portraits of the Barack and Michelle Obama are imbued with the notion of the American dream. Although Wiley is not the first black artist to paint an official presidential portrait—that accolade goes to Simmie Knox, who painted the official White House portrait of Bill Clinton—Wiley and Sherald are the first black artists to paint the official National Portrait Gallery presidential and first lady portraits, a tradition that started in 1994, with Ronald N. Sherr’s portrait of President George H.W. Bush, and, in 1998, with Aaron Shickler’s portrait of Hillary Clinton.

Wiley, like President Obama, was born to an African father and an American mother, whom he was solely raised by. Coming of age in South Central Los Angeles, Wiley found solace in creating art. He escaped the violence-torn neighborhood of his youth for the San Francisco Art Institute before going on to attend an Ivy League school—one of the many marks of the American dream—earning an M.F.A. from the prestigious Yale University School of Art, which launched him into a successful art career. In his speech at the portrait unveiling, Wiley thanked his mother, Freddie Mae, for making sacrifices to buy him art supplies. “We didn’t have much, but she found a way to get me paint, and the ability to be able to picture something bigger than South Central L.A. where we were living,” Wiley told the audience. “You saw it. You did it.”

Sherald, too, is an image of American success. Born in Columbus, Georgia, Sherald knew from an early age that she had a gift. Ultimately, she enrolled at Clark Atlanta University, where she earned a B.A. in painting before moving to Baltimore, her current home, to earn an M.F.A. at the Maryland Institute College of Art. In 2004, Sherald was diagnosed with congestive heart failure. It would be eight years until she received a heart transplant, continuing her practice as she recovered. Only after she won the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition for the National Portrait Gallery did her mother, long skeptical of her daughter’s desire to paint, believed that she could make it as an artist. “She stayed faithful to her gifts, she refused to give up on what she had to offer to the world and, as a result, she is well on her way to distinguishing herself as one of the great artists of her generation,” the former First Lady said at the unveiling ceremony.

Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

The subjects of the portraits—Barack and Michelle Obama—are the very image of the dreams pursued by Wiley and Sherald. President Obama was born in Honolulu and raised in a single-parent household. He only met his father once. As a teenager, the President stayed behind in Hawaii to finish high school while his mom moved with his half sister to Indonesia to do field work. Like, Wiley, President Obama reached the Ivy League ranks after transferring to Columbia University from Occidental College, and then going on to attend Harvard Law School. He was elected to be the most unlikely of presidents on November 4, 2008, becoming the first U.S. president of color.

Mrs. Obama is the descendant of slaves. She grew up in the South Side of Chicago with her ever encouraging parents and older brother, dodging the violence that plagued the area and immersing herself in her studies. The gifted student commuted three hours round-trip each day to attend the city’s first magnet high school, ignoring teachers who warned her that she had set her sights too high, and tried to dissuade her from applying to Princeton University. Not only did she get in, she also went to Harvard Law School, becoming an attorney before she became America’s first black First Lady.

“We have come so far,” said the former First Lady, citing the impact that a portrait of a black first lady by a black artist will have on future generations. “We still have a lot more work to do, but we have every reason to be hopeful and proud.” Despite the current state of the nation under Donald Trump—the steady decline in opportunity, the widening gap between the rich and the poor, resentment against immigrants and rising racial tensions, Wiley and Sherald’s portraits of the Obamas remind us that the American is dream still alive, and that it is indeed within our reach.