Sam Contis first learned of Deep Springs College, an isolated two-year men’s school in the California desert, while pursuing her MFA on the opposite side of the country at Yale University. The college was founded exactly one hundred years ago by business tycoon L.L. Nunn, who believed that a place with a combination of labor, education, and self-governance could train the country’s next leaders (all male, of course). For Contis, it also seemed like the perfect place to explore the complex nature of masculinity, identity, and community at a pivotal time for so many young men. She first visited the college in 2012, and over the course of four years, photographed its students and landscape extensively. The results were published as the book “Deep Springs,” which was released earlier this summer through MACK, and are currently on view in a solo exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Document’s Drew Sawyer and the artist caught up over lunch at Chipperfield Kantine in Berlin, and chatted about Deep Springs, male intimacy, and the mythology of the American West.

Drew Sawyer—I’m interested in why you chose Deep Springs as a subject. I was reading more about the school and saw that the board had voted to go co-ed in 2012, and that you started shortly after that—although the school is still all-male at this time. Was this part of your interest in documenting an institution that was probably going to be changed forever?

Sam Contis—It added a sense of urgency for sure, but Deep Springs was a place that I had wanted to visit for a long time, before I ever had a sense that it might go co-ed. I’d been interested in making pictures of communities of young men living together, especially during late adolescence and early adulthood. I had just moved to California in the middle of 2012 and, as a photographer, I was fascinated by the mythology of the American West and its relation to the medium. I wasn’t directly interested in documentation per se. Deep Springs seemed to be a place where I could explore these various preoccupations simultaneously—masculinity, identity, the landscape of the West, and the history of photography.

Drew—That’s also a very intimidating place to start! The West is so central to American imaginary as well as the history of photography. How does one do something new with that kind of material?

“Deep Springs,” Sam Contis, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Sam—In a way, it was an overwhelming prospect. Early photographers such as Carleton Watkins, Timothy O’Sullivan, and Edward Curtis created such a lasting picture of the West. At the same time—as rich as that history is—it felt as though there still might be a way to reimagine the Western landscape. Through the pictures we’ve come to know, it can feel rather static—as though it is somehow fixed in another time.

Drew—Right. It seems like a bit of an anachronism.

Sam—Exactly. Either an anachronism or a fantasy, or even a strange kind of memory. The image-culture has given us a collective memory of a place that many of us have never actually visited. I thought, “How do I make it a place that I can relate to? One that I can inhabit?” That seemed like an exciting, if daunting place to start.

Drew—You’re obviously engaging with this history, but the work doesn’t feel bogged down by it. You’re able to explore masculinity, identity, and a certain idea of autonomy that is so closely tied to the American West in this very new and interesting way.

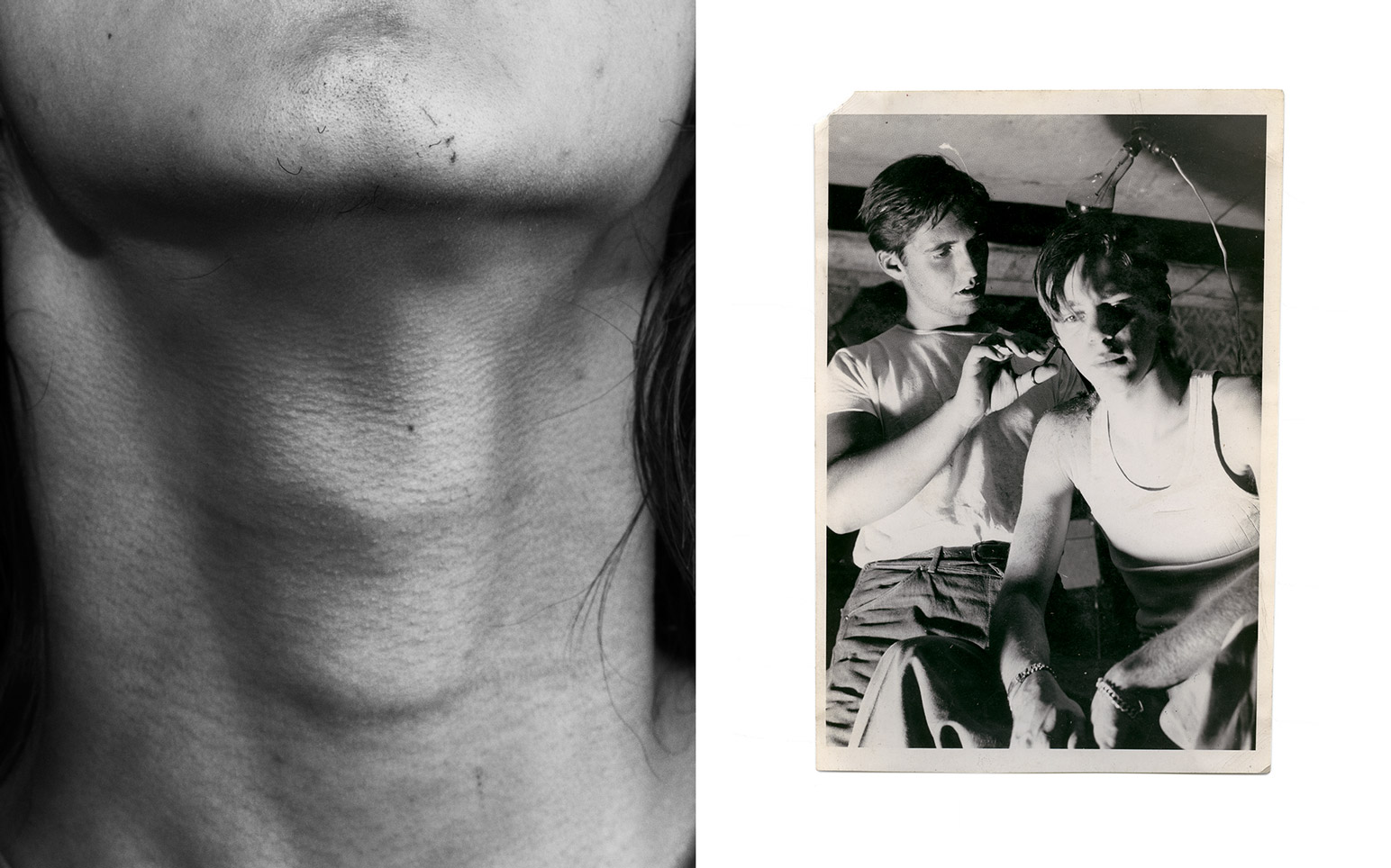

Sam—I wanted to allude to an experience of masculinity that is more expansive and ambiguous than what we might expect in this environment. The earth and body become indistinguishable in a lot of the photographs. I wanted to relate the male body to the landscape, which is often gendered as female. Doing this was a way of dissolving lines of identity, and asking the viewer to reconsider their expectations of the land and the body. I also wanted to show the movement within a landscape that I saw to be malleable and constantly changing. This motion is reflected not only in the content of the pictures but also in the arrangement of the pictures over the pages of the book.

The earth and body become indistinguishable…I wanted to relate the male body to the landscape, which is often gendered as female.

Drew—That leads to another aspect of your book project, which is your use of archival images. Where did you find these materials and why did you choose to incorporate the photographs?

Sam—I came across the photographs while exploring the college’s library. Many of them were in old albums that had been donated to the college by former students or their families. The college was founded in 1917 and a lot of the images that I chose to use are from the late teens, 20s, and early 1930s. I decided to start incorporating the archival images as a way of referencing the place of photography within the history of the American West—as a way giving a historical context to my own images. But I was also fascinated by how the young men back then were using the camera as a tool to explore how we see ourselves in relation to our environment. I was particularly struck by the pictures of cameras: there’s an acute self-consciousness at play. When I see a camera in a photograph I always think of that amazing picture of Parmigianino, “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror,” where the artist reveals his hand in the making of the picture. There are archival images of paintings too: one shows a series of landscape paintings sitting on a cement floor, propped against the wall of a building. The paintings are labeled 1, 2, 3, and 4. I didn’t notice the labels right away. When I first glanced at the image I was confused by what I was seeing. I thought I was looking through a series of small windows out onto a landscape. I loved that I had gotten it wrong in this way. The numbers, to my mind, represent the different ways of picturing the same scene. The photograph itself could be number five.

Drew—There are moments when there are these slippages, when you’re not sure if an image is archival or if it’s one of yours. You were saying it provides context, but it also shows a certain continuity.

“Deep Springs,” Sam Contis, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and MACK.

Sam—I think you’re right. Just as some of the archival images seem very contemporary, some of my own pictures look as though they could’ve been made a century ago. Time suddenly feels elastic.

Drew—Some of those archival images were obviously taken by fellow students, and they are quite intimate. Yours are equally, if not more intimate and sensual. I’m curious as to how you went about gaining the trust of the students or becoming close enough with them that they were comfortable with you taking these types of images.

Sam—That’s an interesting question, and I don’t have an easy answer. I was struck by the intimacy that I found in the community, and I wanted to reflect this in my pictures, by getting closer both to the people and the landscape. Deep Springs is a small and isolated place. The students live together, work together, study together, and eat together. That’s part of what interested me in making pictures here. What does it mean to build a community like this in an isolated desert? What does it mean, today, to bring a group of men together to work and to take on the role of the American cowboy?

Drew—Did you show them pictures along the way, or did they only see the final book? I’m interested in their reactions and if they started performing more for your camera.

Sam—Typically I don’t like to show people pictures, especially of themselves, too early on in a project. That’s mostly because I don’t want them to become overly self-conscious. But here I wasn’t necessarily worried about people performing for the camera—I actually saw this as an important component of the work. How much of our own identity is performance? How much does it depend on the visual cultural references we have stored in the back of our minds? How does the presence of a camera affect our understanding of ourselves? I wanted the work to elicit these questions. Going back to what you asked, the students did see the work before the book was published. At one point, we gathered together and I showed them projections. That’s not something I’d ever done before—sitting down with a large group of people I’ve photographed and showing them the pictures. Later on in the project I started bringing some prints, too.

Drew—Would you let the students keep them?

Sam—Well, the funny thing is, I’d often offer them a print to keep and they’d ask for a digital version instead. But eventually some of the prints I brought did end up hanging on the dorm room walls. It made me happy to see the students living among the work. It also encouraged me to start making more pictures of pictures. There’s an image in the book of a student’s self-portrait, which he’d made in a painting class. He had taped it to the dorm wall and I photographed it. I liked the idea that here are all these images—self-portraits, my pictures, old western movie posters—percolating through the atmosphere of the place.

“Matrix 266” by Sam Contis is on exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive from now until August 27, 2017.