The collaborators discuss their hiatus from the fashion industry, women designing menswear, and breaking with the need for perfection.

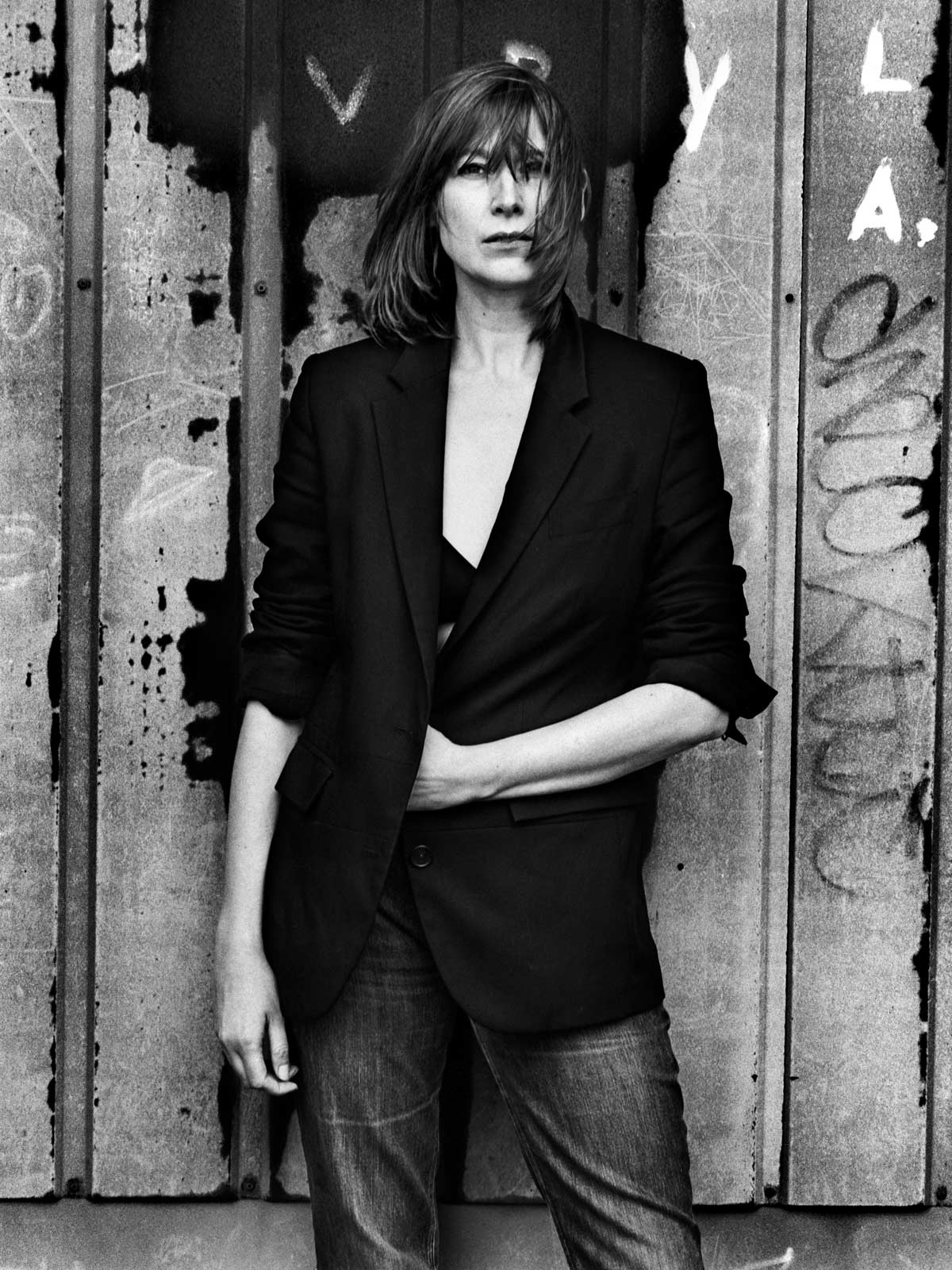

Antwerp is a dark place. The Flemish are a strange people. Yet few Belgian designers are inclined to celebrate that fact. Although their strength lies in storytelling, they rarely tell tales of home—more often preoccupied with exotic locales and dream-like escapism than the grey streets along the Scheldt. Their collective grouping is shrugged off for the most part; each of the “Antwerp Six” and beyond dismisses that moniker with the luxury of hindsight—and their varying degrees of success are attributed to business acumen, to circumstances, and l’air du temps. Of the second wave of talent to emerge from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Veronique Branquinho stands as a lone female voice, her enchanting vision of femininity cocooned in a dark mysticism. Neither wholly conformist nor steeped in the avant-garde, Branquinho’s designs are imbued with an unrelenting romance, their roots in both sartorial and bohemian culture combining to typify Antwerp’s rebellious sensuality. If the designs of her one-time partner Raf Simons represent the punk discord of male youth, then Branquinho’s work mirrors a softer, almost Sapphic allure—celebrating the sacred feminine and the multiplicities of womanhood young and old. Returning to fashion in 2012 after a short hiatus, her label has gathered new potency, its relevance unquestioned amongst the resurgence of a 90s grunge aesthetic and spurred along by two newfound partnerships: the first in collaboration with London-based stylist Panos Yiapanis behind the scenes of her Paris shows and the second in the atelier, with her mentor, fellow designer, and member of the “Six,” Dirk Van Saene, who joins in on the conversation below.

Dan Thawley—How long did you stop the brand for?

Veronique Branquinho—It was from 2009–2012, so three years, something like that. In 2009 I really thought I was done with it. I thought I would turn my back, travel, do something else.

Dan—You went around the world, right?

Veronique—I did two big trips, which was great. When you’re in the business there is no time to travel more than a week.

Dan—Where did you go?

Veronique—I went to the Galápagos Islands, Bora Bora, Australia. I went to Perth, and we took a camper and went to the Outback. It was so amazing; you can camp wherever you want, and you have these amazing views all to yourself.

Dan—Now you’re designing again, with Dirk at your side.

Veronique—Since I started again, Dirk has been helping me and it’s nice. He’s also busy with his ceramics and his own collection.

Dirk van Saene—Again!

Veronique—It’s actually funny to do this interview because normally we work together, and now it’s different.

Dan—You must feel more back in the game than ever.

Veronique—Yes! It is great to have the opportunity to work again in this way, although it’s also very different. It’s really about focusing on the creativity now, which is great and Gibo, [the Italian manufacturer], is taking care of all the rest. This was what was killing me before.

Dan—It’s what is missing in so many brands—infrastructure. To have that kind of backup is great.

Veronique—But of course the pre-collection is somehow the price I had to pay.

Dan—But pre-collection is also something you’ve approached in a specific way too, isn’t it?

Veronique—Yes, I was questioning it because of course the industry demands it in a certain way, and we try to do that. But we have to be realistic sometimes. We are a small team and there is also the question: “Do we want this overload of clothes?” Last time we said, “Let’s just focus on 15 dresses and do something with that.” We have had so many positive comments about that.

Dan—It’s also the way a lot of retailers and designers are going; specialization is becoming more important than ever. It’s more appealing to show something really individual with one direction.

Veronique—That is what I admire so much about Dirk, that he does his thing the way he wants and in the quantity he wants.

Dirk—Yes, but it’s a choice. The way I work, you’re not out there and it’s much less in the spotlight.

Dan—Of course that’s not really what it’s about at this stage.

Veronique—No, and that’s what I sometimes miss with the speed and deadlines. The important thing is you can tell your story and do it at a certain quality with craftsmanship. That is what my experience has taught me all these years. Sometimes you just want to take the time to make one great outfit.

Dan—It’s an exciting time for us to have this conversation with everything that has happened in the last couple of months.

Veronique—Ah voilà! It’s very elegant timing. I think a lot of designers are struggling with the pressure of speed and quantity at the moment.

Dan—For your Spring/Summer 2016 show, we were in the Hôtel d’Évreux, with all those beautiful big globes around the space. Was that the second time you had worked with Panos Yiapanis?

Veronique—It was the third time. I’ve known Panos since I started. It seemed like a good idea to have an external collaborator. He knows my work very well, and we’ve been friends since the end of the 90s. We went to concerts together. Very dark ones! Festivals where only new wave and goth bands would play. He came to Belgium. That’s how we met. It was great to get back on track, and it was the first time we worked together. Suspicious is maybe a bad word, but I’m not used to working like that. He also brought the team, like the casting director Piergiorgio Del Moro. It’s just great energy coming together.

Dan—Had you ever worked with a stylist before?

Veronique—No, never. We did it always on our own.

Dirk—It’s typical for the Belgians, I think.

Veronique—It was a bit awkward for me, because when you make a collection you have a certain vision of how to present it, and you don’t feel there is a necessity for a stylist. But it is also good to see how somebody else sees your work and can make it more focused. That’s what Panos is doing; reducing or concentrating it.

Dan—Which is funny in thinking about some of his shoots, which are the opposite.

Dirk—But I don’t think there are a lot of changes when he looks at the collection.

Veronique—No, we prepare in a certain way.

Dan—It’s an extra nuance…

Dirk—Yes, just a little extra.

Dan—Does he work on the music with you as well?

Veronique—No, I work with Gerrit Kerremans, who was introduced to me by Dirk. We always have this huge discussion because he wants to bring the newest thing, but I’m always very nostalgic! We try to make a marriage. It’s getting better and better.

Dan—And Inge Grognard does such beautiful make up. The winter show with the feathers on the face was so lovely. Your casting has become very interesting—it’s nice to have those emblematic Belgian girls for your shows; it brings back another type of nostalgia for you. What I saw personally was definite self- referencing in the last seasons, which is exciting.

Veronique—Yes, it is something I was running away from a little bit because I wanted to bring something new. But of course you cannot deny who you are and where it comes from. It felt right to re-work—it was never literal, it was always re-worked.

Dan—It feels very much appreciated, I think, by people that know it, and also it’s new to people who are a new fashion audience. It is a strange thing to balance. There are people seeing it with new eyes—people seeing it on Instagram, people who didn’t know who you were before.

Veronique—It’s true. Fashion’s memory is short sometimes. Dan—Goldfish!

Dirk—They have an acute case of Alzheimer’s!

Dan—Are you thinking of doing menswear again? Veronique—It’s so funny when I walk around in Antwerp—so many men ask me, “When are you going to start?” I actually loved doing menswear because it’s a really different way of designing. You never did menswear, Dirk?

Dirk—No.

Veronique—But I liked it because when I’m designing for women it’s like I need to think, I need to feel. Conversely, with men it’s more playful because I just can project what is the most handsome fantasy. How do I like the ideal man? It’s different.

Dirk—More free?

Veronique—Just different, not so existential.

Dan—I feel like women design more masculine menswear than men do.

Veronique—I see that. I also have a love for traditional fabrics, English fabrics, so it’s also a little bit earthier.

Dan—Where in Antwerp is your studio?

Veronique—My studio is actually in Schiplaken! It’s about 20 minutes away from here. Between Antwerp and Brussels. I left Antwerp almost 10 years ago to live a little bit more in the country.

Dan—Do you live there and have the studio nearby?

Veronique—Yes, but soon I will also have a little house in Antwerp because I cannot choose!

Dan—What is the scenery like where you are?

Veronique—It’s like a 70s bungalow.

Dan—Tell me about the apartment in Antwerp.

Veronique—Everything is quite low with the ceiling beams. I bought it in the summer. I just got the key and we would like to do some work. It’s in the student neighborhood, so there were always about three students living in it, so it’s a bit shabby. It’s just great to be in Antwerp again; I missed it. I always came back because my friends all live here, but if you’re not living there you feel like a visitor. Now I’m back!

Dan—That’s nice because a lot of the Antwerp designers like Ann [Demeulemeester] and Dries [Van Noten] don’t live here; everybody else thinks you’re all walking around the city, and it’s not true! You’ve left.

Veronique—Yes, you’re right. I went out of the city when I had my office and shop here, and when I stopped having those I was working and living in Schiplaken. I feel too isolated.

Dan—Do you have to go to Italy for production now?

Veronique—Yes, and Dirk comes along for fittings. We design in our office and then we send them off and choose fabrics there. It was so scary in the beginning, because when I was in Antwerp I had a pattern maker and could see the evolution of the collection every day. I could go up and say, “How is it going?” Now you give a bunch of drawings, and a month later it’s hanging there.

Dan—It’s quite a different process, isn’t it?

Veronique—Yes, but a good process. I was so scared of it, but now I think we understand each other. It’s a luxury, I think.

Dan—It’s so interesting how what they do affects what your product becomes. You have a vision of something, and then the touch and the hand, how they stitch it, the structure all depends on them. It must be so important to you.

Veronique—I think we’re very lucky because Gibo has several factories; we go to Parma which has a lot of craftsmanship. This was one of the problems when I was still in Belgium. It was very much about, “How can we make it to manufacture it? How can we keep the margins down?” It was always about what was quicker. I feel like in Italy it’s more, “How can we make it more beautiful?” It’s great. Of course price point is a reality, but there is a freedom.

Dirk—There are more possibilities; in Belgium there aren’t so many options.

Dan—And in Belgium it’s quite expensive in general, no?

Veronique—Very, very expensive. A lot of Belgium factories are opening in other countries like Poland or Romania. So many factories disappeared since we started.

Dan—What about your stories? When you make a collection, how do you approach each one? Do you collect pictures?

Veronique—I wish I could have more time before each. The reality is that they overlap and it’s about deadlines.

Dirk—Yes everybody is talking about this. But I don’t understand why now all of a sudden. It’s everybody’s first question nowadays “How do you deal with the pressure?” It’s fashion, it has to go so quickly.

Veronique—But there is a big difference between just two collections per year versus four.

Dirk—But all these other people are complaining, and they have dozens of assistants.

Veronique—We cannot compare. We’re such a small group. We have these ping-pong conversations about how we want to proceed. It starts with talking, and this is a very speedy way to go forward. It’s so great that I’ve found Dirk to do this with. It’s not easy to find somebody you can respond to so quickly and who can understand your references. I really enjoy our conversations. Then we do some research, get images, look for the right fabric, and we have another conversation. It goes along that way.

Dan—Do you think there is anything stylistically that Dirk has put inside your collections that is very much his? Or is he more of an accent?

Veronique—He is a help! But it’s very funny—when he’s there I can look at things with a bit of distance. I can look at things from a different angle. He has a very great sense of aesthetics, and I’m very aware of that.

Dirk—It comes naturally, no?

Veronique—It’s very natural! I asked Dirk to be in my jury at the Academy, because Walter Van Beirendonck was teaching. They always ask who you want, and I said Dirk Van Saene! And he came! My first letter when I wanted to find a job went to him.

Dirk—I don’t remember that!

Veronique—“Dear Mr. Van Saene…” I think we phoned and then of course you didn’t need anybody! It’s very funny.

Dan—When did you graduate?

Veronique—1995. I remember when I re-started in 2012 I said to Walter, “Do you know anybody who could help me?” I was thinking of perhaps someone who had graduated from the school and he said, “Why don’t you ask Dirk?” and I said, “I can’t ask Dirk!” Finally I thought, “OK, let’s try this.”

Dan—That’s a lovely story.

Veronique—It’s funny because we can be anywhere—we travel together—and we see in the same moment the same thing and we laugh about the same things. It’s more than a help, I think— I don’t know the word for it. Dirk can filter me in a good way. I can be in doubt sometimes. I like to see both ways all the time. Both stories. He says, “This one is better!” and I can see it more clearly.

Dan—Do you collect art?

Veronique—No, I don’t feel the need to own it. For me it’s fine just to see it; I don’t need to have it. I don’t want to be busy with it like an investment. Maybe some emotional things I would buy, but without any value—just for how it moves me.

Dan—How about your ceramics practice, Dirk? How is that going?

Dirk—It has stopped for a while, now I have to restart. People from galleries keep asking me for new pieces but it’s really too much work. I still teach and I’m doing my own collection. The first one I did recently was only digitally printed dresses. I paint them and then they are scanned and printed. Now it’s less painting and more fabric work—3D things—and lots of handwork.

Dan—Are there any other references that have come into the last few collections you would like to talk about?

Veronique—The next collection is now in my head, and it’s more like a walk in a bare winter forest with shadows in black and white. Some protection against the cold—blanket, a coat…

“When I’m designing for women it’s like I need to think, I need to feel. With men it’s more playful because I just can project what is the most handsome fantasy.”

Dan—Even with just that short description, it is easy to understand how you are an emotional or instinctual designer.

Veronique—Yes, when people ask how is it that I start I think it is always an intuitive process. I don’t know how to do it any other way. It is first about the mood or that you want to see a certain shape, but there isn’t a “why.”

Dan—There are so many people designing today that are collage artists, just putting things together…

Veronique—I love art, I love to see the work. But it’s so strong when I see something from an artist I really like. It’s so overwhelming and so correct in that context that I find it difficult to take that and work from it.

Dan—What I actually mean is that some people don’t actually design—they just copy and paste parts of the past and put bits together.

Veronique—No, no, it’s really the feeling or the shape. Like, last summer we said, “OK we want volume.” So we started with a circle. It didn’t come from an artist, but just the idea of a big volume, a feeling of freedom, the liberty of moving. A circle is the biggest volume you can have—a fluid volume.

Dan—There is always the right touch or twist of something strange in what you do as well. A little bit of perversion, or sexuality. Is that something you think to include from the beginning or decide to twist in during the process?

Veronique—It needs to be there from the beginning. I don’t like perfection or being too literal. I need to be able to break it in order to create a balance. I like references of tradition, but if you just do tradition there is no point of me being there. It’s something we think about. The beauty of imperfection is very important. It’s also not always done in fashion. People are preoccupied with always going for beauty, but for me beauty is also about being vulnerable and bringing something in that maybe shouldn’t be there.

Dan—A bit fragile?

Veronique—The fragility and vulnerability of beauty.

Dan—We’ve only met a handful of times over the years, but for me it feels like you haven’t changed. You look and sound the same. In saying that, do you think that the woman you design for has changed at all? Does the instant visual nature of the industry have any effect on you?

Veronique—It’s certain that the whole world is very busy with images. I cannot work like that; I’m still concerned about content, intensity, integrity. I cannot just do images. I’m not selling air. I guess it’s not easy to find our public. It was so great when I had the shop in Antwerp. It’s so great to have the contact with the customer. I always liked that it was not only a high fashion customer; it’s somebody who appreciates the cut, and makes it her own.

Dan—There was an intimacy.

Veronique—I miss that sometimes.

This conversation first appeared in Document’s Spring/Summer 2016 issue.